Plant proteins bring a lot to plant-based meat analogues, from nutrition to fibrosity, yet their lack of lubrication has been considered a barrier in their providing the right texture to consumers.

The study used pea and potato proteins, both of which normally suffer from too much friction in their mouthfeel.

The power of microgels

Microgels, a type of network of proteins, were key to the study, allowing the researchers to add lubrication to plant proteins.

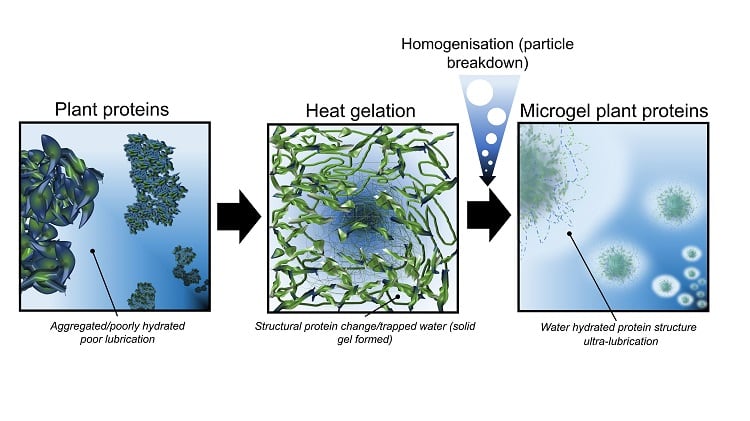

The pea and potato protein were hydrated, gelled and homogenised into four types of microgels, through a process called microgeletion, which were tested for their ability to increase the lubrication of the protein.

This is done by placing the plant protein in water and heating it, changing the composition of the protein molecules, causing them to come together to trap water around it, forming a network or gel. They are then “homogenised”, breaking the protein network into a network of tiny particles, or a microgel.

When they are put under a similar level of pressure to when they are being eaten, they tend to ooze liquid, with a similar viscosity to that of single cream. This creates the juice-like sensation of real meat.

They were tested out by using tongue-like surfaces that acted as a substitute to a human tongue, which evaluated the mouthfeel of the different microgels.

“What we have done is converted the dry plant protein into a hydrated one, using the plant protein to form a spider-like web that holds the water around the plant protein,” said Professor Anwesha Sarkar, who lead the study.

“This gives the much-needed hydration and juicy feel in the mouth.

“Plant-based protein microgels can be created without having to use any added chemicals or agents using a technique that is widely available and currently used in the food industry. The key ingredient is water.”

To ensure that their findings were correct, they used atomic force microscopy, which scans the surface of a molecule to get a picture of its shape. The results showed that they were correct.

“Seeing the images from the atomic force microscope was an exciting moment for us,” said Professor Sarkar. “The visualisations revealed that the protein microgels were pretty much spherical and not aggregating or clumping together. We could see individually spaced plant protein microgels.

“Our theoretical studies had said this is what would happen but there is nothing quite like seeing it for real.”

Consumer acceptability

With texture often offering a barrier to consumers accepting plant-based proteins, the researchers hope that the new study will break down the barriers to its popularity.

The microgels have the lubricity of a 20% fat emulsion, so they can potentially be used as a substitute for fat in plant-based meat.

Sourced From: Nature Communications

'Transforming sustainable plant proteins into high performance lubricating microgels’

Published on: 7 August 2023

Doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40414-7

Authors: B. Kew, M. Holmes, E. Liamas, R. Ettelaie, S. D. Connell, D. Dini & A. Sarkar