Scientists at Aberystwyth University led by Professor John Draper have developed breakthrough urine biomarker technology that can monitor eating behaviour, with the aim of tracking human interactions with food chemistry and linking diet to long-term health. “We are looking at what chemicals are in food and how humans interact with them,” Professor Draper told FoodNavigator during a recent visit to the University’s Department of Life Sciences.

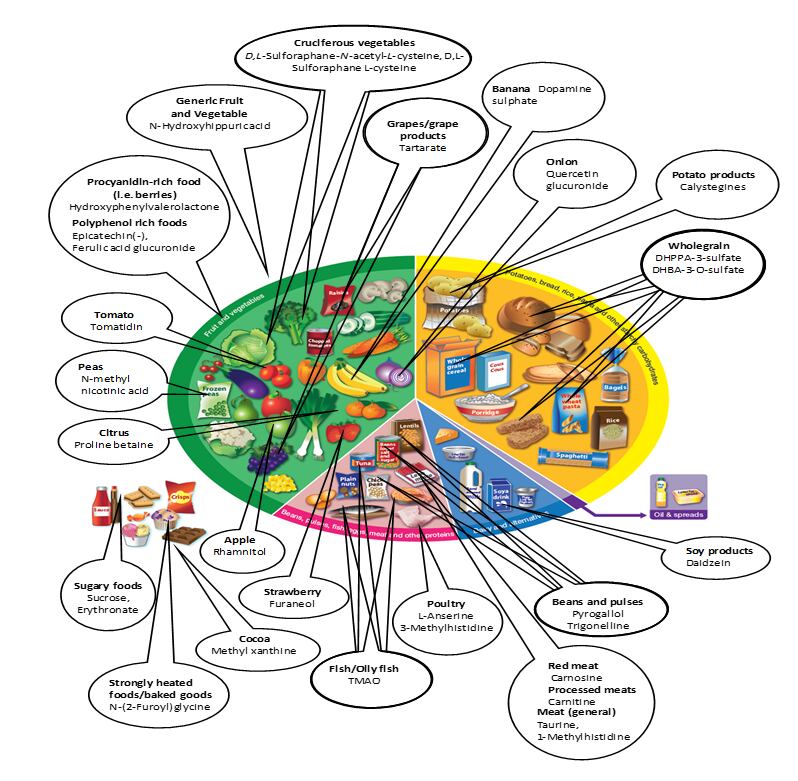

The project pursued two strands of research, assessing the chemical makeup of food and understanding how these metabolites ‘track through your body’ using urine or blood spot samples. The result of six-year’s research, Professor Draper explained, is a map of the ‘biomarkers of diet’. Chemicals derived from different foods cause 'distinctive changes' in urine metabolome that can be detected through mass spectrometry. “Chemicals in urine can distinguish between our exposure to individual foods,” Professor Draper said.

This means the researchers can identify the 'chemical fingerprint' of food after consumption through urine tests. Specific chemicals in urine can point to exposure to individual foods and food groups. For example, the biomarkers of meat or fish consumption can be measured by Tripe Quadrupole LC-MS/MS; for poultry, you would find L-Anserine and 3-Methylhistidine; for fish, you would see TMAO; and for red meat, you would detect carnosine.

From functional foods to nutritional guidelines

Potential applications include the development of functional foods and more nuanced dietary guidelines.

As part of the Future Foods project co-funded by the Welsh government, it is hoped the biomarker breakthrough can boost industry innovation in functional foods. “We don’t all interact with chemicals in the same way. Proving a link between a food or supplement and health is a massive ask,” the food scientist explained. “We are trying to set up in the UK a pipeline to engage properly with health claims… This pipeline is very important because the UK doesn’t come under the EFSA process anymore. It is about providing a technological interface for small, medium, or large companies. We want to have a system in place that makes it accessible for any company to get objective feedback on whether they can make health claims."

“Through Future Foods, we’re developed a lot of collaboration with the food industry. We’re aiding the research and development behind anecdotal claims,” added Aberystwyth’s Dr Amanda Lloyd.

The second objective is the ambition to help develop nutritional labelling and guidance that is more effective at supporting public health objectives. “Our main mission is to put science behind food labels to address issues of nutrition quality and functionality,” Professor Draper revealed.

The UK’s National Dietary Survey, on which national dietary guidance is based, is reliant on self-reporting and this is ‘inherently inaccurate’, FoodNavigator was told.

And it isn't just the UK that relies on self-reporting. Most national nutritional guidelines or nutritional labelling schemes are based on what people admit to eating. "Numerous studies conducted to assess the factors impacting food choices and eating behaviours were mainly based on direct protocols in which the participants were directly questioned... These direct methods may induce biases in responses, especially due to the social desirability effect.”

To address this, Aberystwyth researchers decided to develop a new technique to track diet that is more objective and doesn’t reply on self-reporting. The outcome is a urine test that can be carried out at home, alongside the biomarker panel that can accurately identify what has been eaten. Professor Draper said the test kit is relatively cost competitive compared to traditional health survey methodology, which requires researchers collect and collate data. Public Health England is currently assessing the test and Professor Draper is hopeful it could be used to help further develop the Eatwell guide.

Moving beyond one-size-fits-all nutritional advice?

An ambition to move beyond general claims and advice was recently raised in the now highly politicised debate over European plans to introduce front-of-pack nutritional labelling. The NutriScore scheme, widely viewed as the front-runner in bloc-wide mandatory requirements the Commission is set to introduce this year, has faced mounting criticism over the calculations it uses to decide the healthfulness of foods.

“Science is moving in the direction of personalised diets,” Pietro Paganini, founder of Competere.eu, argued at a recent debate on the subject hosted at the European Parliament. "Your smart watch is linked to your fridge, your metabolism and the supermarket. This is a great revolution in nutrition, where research on DNA and genetics is leading us towards personalised diets. Nutri-Score is the past. It’s a one-size-fits-all scheme that is the old Hegelian model where an elite group of scientists approve an algorithm that claims to be perfect and applicable to everyone. Yet, when political or commercial interests decide so, the algorithm can be changed, and grades for selective products can go from red ‘E’ to yellow ‘C’.”

Professor Draper doesn’t think we are here yet. Observing that personalised nutrition is a combination of two factors - a person’s inherent nutritional metabolic phenotype and their nutritional status – he believes ‘the assumption made by the algorithms running these systems are largely naïve in the extreme’.

“I would not recommend any personalisation of labelling but validation of nutritional content of foods instead. Then consumers who understand their personalised nutritional metabotype in the future can make informed decisions.”

However, he does see areas where existing nutritional labelling and recommendations can be strengthened. For instance, current systems are based on nutritional content and fail to take into account issues like nutritional quality and bioavailability. “There is a real need to develop new standardised assays for nutritional quality in relationship to important complex food characteristics (such as protein content and quality and vitamin bioavailability) using the final processed food products. Just listing ingredients and calculating what might be in a product and whether it is available in the right form to benefit humans is inadequate.”

‘Labels do not cause but allow healthier choices’

For any of this to have a positive impact on population health, it also needs to resonate with consumers and change our eating patterns. European consumer organisation EUFIC stands firmly behind the introduction of FOP labelling to empower consumers to make more informed decisions.

Accurate food labelling is needed to help us understand what is in the packaged food we buy. “The final aim of front of pack nutritional labelling is to enable, empower and help consumers to make informed, healthier food choices,” Dr Laura Fernández Celemín, EUFIC’s Director General, observed.

EUFIC is less convinced that personalised nutritional labels are the way to go.

The organisation recently carried out a consumer research project with the aim to examine how best to communicate to consumers about healthy and sustainable food, called ‘Bridging the gap between healthy and sustainable diets’. “We found that in several EU countries consumers preferred having a standardised nutrition label determined by an EU/national body rather than having a personalised nutrition label,” Dr Betty Chang, Research Area Lead at EUFIC, told FoodNavigator.

Dr Celemín stressed labels alone won’t improve population health: “FOPNL does not cause but has the potential to allow healthier choices.”

The main bottlenecks limiting the impact of nutritional labelling are lack of motivation, lack of attention and ‘to some extent’ the format of the label. Importantly, the availability of healthy options also needs to be addressed, the consumer advocate noted.

“On the product availability, we can definitely improve the healthfulness of the offering, recognizing that labelling can act as an incentive for product reformulation and innovation. It should not be forgotten that labelling competes with other factors that influence consumer decisions, like price, taste, habitual buying or convenience. In the literature, we find those and other barriers that are interrelated, such as low nutritional knowledge and low numerical literacy, which is associated with a lack of resources to educate. This emphasizes the importance of placing greater focus on education as an instrument to improve motivation, knowledge and confidence, and thus allowing labelling to act as support tool to improve consumer choices,” she told FoodNavigator.

“Although the effects of nutritional labelling may be modest, they should not be underestimated, as changes of small magnitude can have significant effects is sustained in time and if they happen at the population scale. FOPNL should not be considered a ‘magic bullet’ but should be seen in the context of other public health programs and policies.”