Strolling down the aisle of any supermarket, consumers are met with ‘natural’ claims left, right, and centre. But in Europe, no legal definition of the term ‘natural’ exists. What is meant by ‘all natural ingredients’, ‘100% natural’, and ‘natural colours’ – claims commonplace on-pack – is therefore open to interpretation.

At the same time, on the global stage, novel technologies are coming to market. Precision fermentation technology is producing bio-identical dairy proteins and real meat is being grown in labs from animal stem cells. Both of these lab-grown alternatives mimic traditional, familiar products consumers have long considered ‘natural’.

Could that make them ‘natural’ too? FoodNavigator investigates.

What is ‘natural’ in conventional animal protein production?

There is a disaccord between what consumer perceive to be ‘natural’, and the way the term is currently used by food and beverage manufacturers. Much of what was truly ‘natural’ at some point in our history, is ‘natural’ no longer.

This is the perspective of Maija Itkonen, Co-founder and CEO of Onego Bio, a Finnish start-up leveraging precision fermentation technology to develop animal-free egg white protein, ‘bioalbumen’.

“Especially in the protein field, [production] has been, for a very long time, very unnatural,” she told delegates at Future Food-Tech in London.

Indeed, many of today’s egg production systems are a far cry from traditional, pre-industrial agricultural methods. And an even further cry from egg production in the wild.

The closest industry comes to these methods today is likely obtained in organic systems, whereby chickens are able to feed themselves with organic feed, and have enough space to run around in. In Europe, this means one chicken has four square-meters of outdoor space, and a sixth of a square indoors. In comparison, a free-range hen only gets a ninth of a square metre indoors. For hens in egg ‘factories’, the situation is more dire.

In Onego Bio’s native Finland, organic egg production accounts for just 6.8% of total egg production, according to Statista.

“We are now in a situation where we have to choose between ‘traditional’ [food] – which could perhaps have been classified as ‘natural’ a long time ago… – or search for a new way of producing [these same foods],” said Itkonen.

This latter option is Onego Bio’s approach. In trading in traditional animal farming for microorganisms and bioreactors, the start-up hopes to sell animal-free ‘bioalbumen’ to bakery, confectionery, and sports nutrition markets.

Dairy is another area largely eligible for the ‘natural’ claim, suggested Itkonen. But milk cartons carrying imagery of happy dairy cows in lush pastures is not a true representation of where food comes from, we were told. “It’s perceived to be natural, but it’s not the truth.”

‘It’s natural if consumers know where it comes from’

In plant-based, the same animal welfare concerns do not apply.

The definition of ‘natural’ for Kraft Heinz, which largely works with plant-based ingredients, is at least two-fold. “Leaving taste aside, there are two key elements for me: the product needs to be trusted, and it has to be recognisable,” Miriam Ueberall, Head of R&D International, Kraft Heinz, told delegates at Future Food-Tech.

Trust is all about transparency for the R&D lead. Consumers must know where the product comes from, she stressed. “This is an obligation that we have as an industry, to take consumers on a journey and help them understand [the product’s provenance].”

Being recognisable means helping consumers understand that what is happening at large-scale behind closed doors in factories can be comparable to what is happening in the home environment, we were told.

It is here that Ueberall and Itkonen perspectives diverge. Even at a miniscule scale, Onego Bio’s animal-free egg protein cannot be reproduced in the home.

Ueberall continued: “Our Heinz Ketchup, manufactured [at large scale], is a ‘natural’ product in my eyes,” said Ueberall. “It contains tomatoes, vinegar, soy, sugar and spices. There is nothing else in it. And the process [could be] followed at home. You can produce that exact same ketchup [in your kitchen].

“It might be a bit grainier, it might taste a little bit different, but you can make it at home. We just happen to make it at a really large scale and sell it around the world.”

The company’s perception of ‘naturality’ aligns with industry’s interpretation of ‘clean label’ – which similarly lacks an official definition. “Consumers very clearly demand more ‘natural’ products, and that is often translated into ‘clean label’ solutions,” said the R&D chief.

“On average, we are seeing products with shorter ingredients lists, with more recognisable descriptors, and I think that’s driven by consumer expectations and [demand].”

Forget ‘natural’, let’s make healthy food

What else might consumers perceive to be ‘natural’? It’s likely consumers associate ‘natural’ with fresh, unprocessed foods, such an apple, suggested Halim Jubran, Co-founder and CEO of Phytolon – an Israeli start-up using precision fermentation to develop natural colours for food applications.

“But most of our food today is processed food. If a product is comprised of ‘all natural ingredients’, [what prompts a consumer to] opt for ‘natural’?”

According to McKinsey & Company research, healthy eating is important to consumers. In a survey conducted with 8,000 participants from the US, UK, France, and Germany, at least 70% of respondents said they wanted to be healthier and 50% said healthy eating is a top priority for them. For this half of consumers, healthy eating means reducing consumption of processed food and sugar, as well as fat, salt, and for some, red meat.

“Of course, ‘natural’ can have a regulatory aspect and a psychological aspect, but I think we as innovators and manufacturers have to look at the what the consumer wants,” said Jubran, stressing that health should also be a top priority for manufacturers.

Everything else is a question of semantics, he suggested. If industry ensures food is healthy – which is what the consumer wants – ‘why define food as natural or not natural?’

Others agree. “Whether something is ‘natural’ isn’t really important. What is important is: is it healthy for you? And is it healthy for the planet?” said Shilei Zhang, Chief Commercial Officer at Solar Foods, whose Solein protein ingredient – made from CO2, air and electricity – recently received regulatory approval in Singapore.

Zhang is unconvinced consumers’ perception of ‘healthiness’ aligns with reality. The example the CCO offered is pork – a product consumers associate with familiarity and healthiness. However, pork is often sold in a processed format – for example as sausages or as cured meat – and production is a major source of ammonia, raising environmental concern.

“I don’t think that perception [of healthiness] is always true, and that’s why our job is to change the perception. A key way to do that is by being transparent about what we do.”

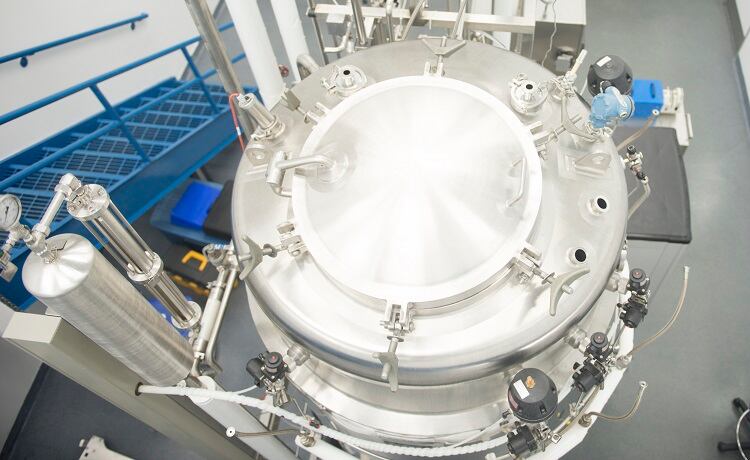

Solar Foods aims to be as transparent as possible, suggested Zhang. The start-up works with a ‘natural’ microbe, which is ‘taken from nature’ and not modified in any way. “We are also very transparent about the rest of the production progress, which is not something you find in nature,” he continued, alluding to the gas fermentation reactor central to Solar Foods’ technology. “It’s really important to be transparent.”

Can food be ‘natural’ if it was grown in a lab?

Can food be considered ‘natural’ if it was grown in a laboratory rather than on a field or in a paddock?

It depends on the production method, according to Phytolon’s Jubran. It’s possible to replicate almost any ‘natural’ ingredient by synthesising it chemically in the lab, he explained. This happens often. Beta carotene, for example, is a red-orange pigment found in plants and fruits. In most supplements, however, synthetic beta carotene is used. And consumption of synthetic beta carotene has been associated with increased cancer risk.

“There is a difference between chemical synthesis and biological production,” Jubran continued. Phytolon is developing betalin pigments, including beta carotene, via fermentation of genetically engineered baker’s yeast.

“We’re using natural components together to produce a natural product that in my opinion can be labelled as ‘natural’, because it is.”

Consumers have, in fact, been consuming lab-grown food ingredients in foods they largely consider to be ‘natural’, for decades. In 1990, precision fermentation-derived rennet was developed for cheesemaking. Prior to this time, rennet was extracted from the stomach lining of young cows. Today, around 80% of the rennet used in cheesemaking comes from microorganisms, rather than livestock.

Developing rennet in a lab was a ‘brilliant idea’, according to Onego Bio’s Itkonen. Cheese is largely considered a ‘natural’ product, and Itkonen queries whether consumers would actually opt for a ‘natural’ cheese that ‘requires baby cows [to be slaughtered]’ over a cheese made ‘using the same natural enzyme produced in a bioreactor’.

It’s a question of familiarity… so how can lab-grown foods become more familiar?

Just as Kraft Heinz’ Ueberall suggested ‘natural’ food should be recognisable to consumers, the food tech players conceded familiarity is important. But all food products were unfamiliar at some point, stressed Onego Bio’s Itkonen.

“It’s good to keep in mind that everything has been somewhat invented. Bread didn’t just appear from somewhere. Wine was also invented. It just seems ‘natural’ because we’ve been producing it in a similar way. But we’re moving forward every day, things are changing, and we are [developing] different practices. Otherwise, we’re stuck in the past.”

Indeed in some geographies, fermentation is a much more familiar technology than in others. When Solar Foods speaks with food companies based in Japan and China, where fermented food is ‘extremely familiar’ to consumers, it is deemed ‘very natural’.

“There are a lot of nuances here in terms of cultures and countries,” explained Zhang.

As for consumers for whom Solar Foods’ technology is ‘not that familiar’, there is work to be done. The perception of ‘naturalness’, in this instance, will likely not apply. “Therefore, it’s important to change that consumer perception, to [help them understand] it is not a weird, unnatural thing.

“This is how we do things and change the root cause…so it is more familiar to consumers and one day it will be more naturally labelled.”

Phytolon has already observed early signs of changing perceptions. “Recently, we’ve seen some success stories. This is the drive that the food industry needs in order to accept innovation that comes from biotechnology, that comes from fermentation,” said Jubran.

“Success stories can promote the final step towards the revolution that has been going on for the last few years.”