The Cavally forest reserve in Côte d’Ivoire is falling victim to deforestation at the hands of smallholder farmers seeking fertile soil for cocoa production.

Together with the Ivorian Ministry of Waters and Forests (MINEF), the national forestry agency (SODEFOR), and food giant Nestlé, NGO Earthworm is initiating a new project designed to protect and restore the reserve.

Rather than evict smallholders operating illegally in the area, the project is centred around farmer engagement, Earthworm’s Côte d’Ivoire country director Gerome Tokpa, told FoodNavigator.

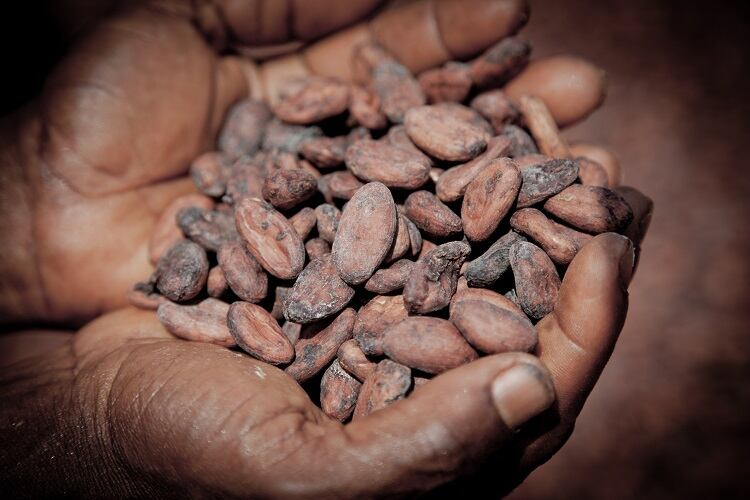

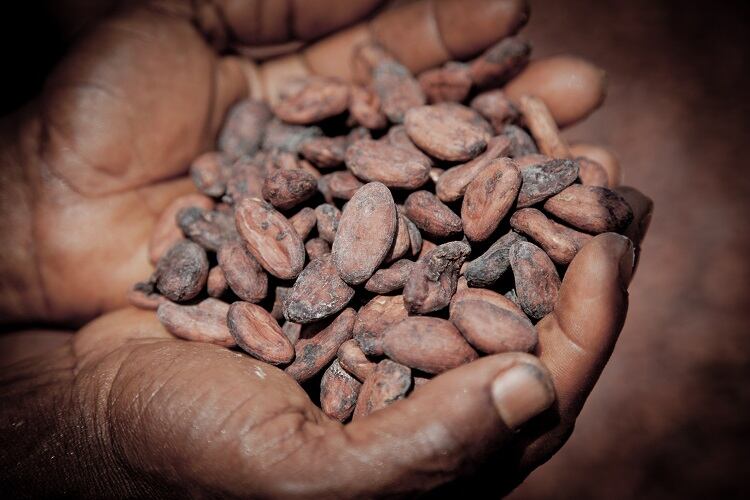

Cocoa in Cavally

More than one-third of all cocoa used in chocolate comes from Côte d’Ivoire on Africa’s west coast. This year, the country was predicted to produce more than two million tonnes of the sought-after commodity.

It is no coincidence that the country with the highest cocoa production is simultaneously struggling with deforestation. Côte d’Ivoire boasted 16m hectares of forest back in 1960, but by 2015 had just 3.5m hectares left.

A large proportion of this forest loss – an estimated 60% - has been associated with smallholder agriculture, with a significant percentage thought to be linked to cocoa production.

This is because forests create the essential climate needed to grow cocoa. “Farmers are looking for fertile soil,” explained Earthworm’s Topka, which they find ‘only under big trees’ in forests.

Cavally is one of 234 classified forests in the country. Covering an area of 67,593 hectares, the forest is located in western Côte d’Ivoire, and is home to several endangered species including chimpanzees, forest elephants, and pygmy hippos.

Deforestation is rife in Cavally, where much occurs beneath the canopy. This makes it more challenging to monitor.

‘A forest reserve is meant to be a forest reserve’

However in recent years, Starling technology – the result of a partnership between Earthworm Foundation, Nestlé and Airbus which uses satellite and radar imaging tech – has been able to penetrate beneath the canopy, and better identify cases of deforestation in the region.

Since SODEFOR began using Starling in December 2017, deforestation in the region has declined: between January 2018 and June 2019 the rate of deforestation decreased by 7.4%.

“The trend of deforestation decreased immensely,” explained Tokpa. “But we could see that deforestation didn’t stop.”

A decreased rate is not good enough, he suggested. “A forest reserve is meant to be a forest reserve. People are not allowed to do agriculture inside. Cocoa farming [in the forest] is illegal.”

Over the next three years, MINEF, SODEFOR, Nestlé and Earthworm will implement a plan to protect the reserve. Ultimately, the goal is to restore the rainforest. To do so, the project will also work with farmers in the area, and aims to improve their livelihoods in the long-term.

Finding a solution

Cocoa production is of immense importance to the Ivorian Government and its occupants. Around one million smallholders operate across the country, a significant number of which are presumed to work in forests.

Cocoa production is not the only illegal practice taking place in Cavally. Rubber is produced on the periphery of the forest reserve, and illegal mining takes place in the north western region, Tokpa explained. But it is ‘mostly cocoa’.

Finding a solution to these illegal practices is complex. Evicting cocoa farmers in the area is not the answer, said Tokpa, as it has been estimated that one-third of Ivorian cocoa is produced illegally in forests. “We cannot just say ‘Farmers, you have to go out of the reserve’ without giving them the possibility of [alternative] solutions.”

From an economic standpoint, evicting smallholders from forests could also cause issues at a national level. “Economically it could be a problem for the country,” explained the NGO’s Côte d’Ivoire chief, “the country relies on the cocoa business”.

Rather, it is about meeting somewhere in between, finding a ‘middle ground’ so that the farmers can continue producing.

“We want to be operational on the ground,” said Topka, who is wary of decision makers – with limited experience in agriculture – ruling from afar. “A lot of people are speaking in the name of the farmers, but they [themselves] have never been farmers. You have to have your feet on the ground, to see how they are living, see how they do cocoa business, [before] speaking in their their name.”

Approaching food businesses with ‘five pillars’

When seeking industry players to contribute to the project, Earthworm approached some of the biggest names in the business, including Nestlé, with a five-pillar plan.

Firstly, the project sought to identify some ‘density patches’ in the reserve. Of the 67,593 hectares that make up the Cavally forest, a total of 57% remains completely preserved. It is this 57% that the initiative is looking to protect.

Outside of the 57%, there are ‘a lot’ of degraded areas in the reserve, Topka continued, which the project aims to restore.

The third pillar focuses on farmer – or ‘pupil’ – education. “We need to accompany the pupils operating inside the reserve. The forest is a no-go area, they should not be in there doing agriculture. So we need to find some alternatives for them outside the forest reserve.”

Potential solutions include identifying areas at the forest’s periphery where farmers can set up new cocoa plantations. Alternatively, potential locations could be found beyond the periphery. “We need to find a transition pathway for those farmers inside the forest reserve. We cannot just throw them outside.”

Discussions also need to take place with landowner 'pupils' currently working in the periphery. In this way, farmers can learn sustainable farming techniques and develop more ‘resilient’ livelihoods.

This may also help ensure a smooth transition for both parties, explained Topka. Approximately 90% of farmers working inside the reserve are from Burkina Faso. Landowners may not be accepting of help being given to ‘illegal’ farmers from a neighbouring country, Topka suggested. However, if landowners’ yields increase thanks to sustainable farming techniques, they may be more accepting of the situation, he added.

The final pillar addresses scale. “If we succeed in the project in the forest reserve and its periphery, then we will want to scale up. [This issue] is not just one case. We also have other forest reserves in Ivory Coast who are facing the same challenges.

“So we are proposing that afterwards, we scale up to other forests reserves in the Ivory Coast.”

Nestlé onboard

Swiss food giant Nestlé is contributing around 75% of the budget required for the Cavally project.

Earthworm is still in discussions with other food businesses and hopes to secure the remaining €800,000 required for the project.

Nestlé’s Cocoa Plan manager, Darrell High, said the company is ‘delighted’ to kick off the project. “Our contribution to the restoration and reforestation of the Cavally Forest is part of our commitment to make sure that no cocoa we buy is linked to deforestation and our pledge to achieve zero net emissions by 2050.

“We believe that a sustainable production of cocoa that benefits local communities and the environment, and spurs economic development, is possible. Collaboration will all key stakeholders will be key to achieve this vision, and this project is a first step in that direction.”