The World Food Programme (WFP) addresses hunger and promotes food security for 87 million beneficiaries in 83 countries around the globe each year.

Similarly to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), WFP – which is also an affiliate of the United Nations – is headquartered in Rome, Italy.

The food-assistance not-for-profit has been operating under lockdown since the Italian Government implemented nationwide isolation measures on 9 March. Under its business continuity plan, all WFP staff are working from home, Acting Director of Supply Chain, John Crisci, told FoodNavigator.

The same goes for employees in its field offices. “It’s the best ‘stress test’ the business continuity plan has ever gone through in the history of WFP,” we were told.

Even amid a coronavirus pandemic, Crisci stressed that WFP’s line remains clear: “We will leave no one behind, which has always been our slogan.

“We are prioritising based on availability, pipelines, and stocks in countries. What we have, we are allocating to where the most immediate needs are.”

How is coronavirus affecting food security?

From a European consumer perspective, coronavirus’ impact on food security is obvious. Depleted supermarkets shelves have become commonplace in many of the affected regions as retailers adjust to heightened demand.

“Some of the things we’re seeing, that are affecting food security – even in developed countries – include panic buying,” WFP’s Crisci told this publication. “This is reducing market access, in the sense that there are empty shelves for certain items.”

In Italy, where the supply chain chief is based, the outbreak has also had an impact on purchasing behaviour, he explained. “The Italian tradition has been to buy on a daily basis, now it looks like people are buying on a weekly basis.”

However, food and agriculture sectors should, in principle, be less affected, Crisci continued. The disruptions affecting food security will be – and are currently – occurring as food travels the supply chain from farm to fork.

“Some of the impacts of COVID-19 include illness related to workers within our operations and with key stakeholders we work with, storage, transport interruptions, and quarantine measures – including a 14-day anchorage period for vessels.

“Such challenges can disrupt the food supply chain, lead to food losses and the unnecessary waste of supplies during these difficult times.”

The World Food Programme (WFP) is the food assistance branch of the United Nations. Committed to the international goal of ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition by 2030, WFP distributes more than 15 billion rations to around 83 countries per year.

WFP focuses its efforts on emergency assistance, relief and rehabilitation, development aid and special operations. Two-thirds of its work is in conflict-affected countries where people are three times more likely to be undernourished than those living in countries without conflict.

At the same time, the UN branch is investigating how border closures could impact food security. For now, governments ‘seem to be willing’ to continue cross-border trade to allow the flow of goods.

“The World Health Organization (WHO) continues to advocate for no restrictions to transport and trade, however countries will act based on their own risk assessment, and some supply chains may be disrupted.”

Problem areas: ‘My greatest fear is Africa’

As of yesterday (24 March), Italy had the highest coronavirus death toll at 6,077. Total reported cases stood at 63, 927.

However, WFP has not been redeployed to boost food security in local regions. “We are, in some cases, providing logistical support. Vice versa with countries that want to donate medical equipment and items to countries in difficulty,” Crisci explained, adding that much of this logistical support is provided through air lifts.

For the UN branch, key focus regions remain the Middle East and Africa. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, all these regions – which in Africa include western, southern and eastern regions – experienced difficulties in ensuring food security.

This was heightened by western Africa again battling Ebola, South Africa’s recent drought, and swarms of locusts in eastern Africa, the WFP executive explained.

“COVID-19 has compounded that even further. Operations continue to move with some disruptions along the way, but we are prioritising and trying to meet the needs of beneficiaries.”

“Every country we’re operating in is affected by the virus. That can be lockdown, or that can be limited movement, but all the countries we’re working in have some form of effect from COVID-10” – WFP Acting Director of Supply Chain John Crisci

As the outbreak progresses, WFP’s supply chain plan is to ‘front load’ its operations globally with three months worth of food on its ‘major corridors’ before more activity is shut down.

Speaking from a personal perspective, rather than on behalf of WFP, Crisci revealed that moving forward, Africa is his ‘biggest fear’ amid the coronavirus crisis.

In Europe, Italy has reported the most COVID-19 cases. As of yesterday (24 March 2020), the country had reported 63,927 cases and 6,077 deaths.

In the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Iran is currently the worst hit, with a reported 23,049 cases and 1,812 deaths. This is followed by Pakistan, with 887 reported cases and 6 deaths.

In the African Region, South Africa has reported the most number of cases (402). There have been no deaths in South Africa to date. Algeria, which is ranked second with 231 cases, has reported 17 deaths in total.

“We’re doing a lot for Africa in our contingency planning,” we were told. “Europe is alarming [Italy, Spain, Germany, France, and Switzerland are some of the hardest hit currently], but Europe has the facilities, infrastructure, and medical systems in place.

“There is good awareness [in Europe], so it slows down the spread. Whereas in Africa, it can go like wildfire.”

Key challenges

WFP has significant experience in virus outbreaks, as one of the bigger players during the Ebola epidemic of 2014.

The western African Ebola virus epidemic was the most widespread outbreak of the disease in history. “What we learned from there is helping us put together strong contingency plans,” explained Crisci.

The UN branch’s greatest test is therefore not operating with a scaled back team, or implementing new business continuity measures, but ensuring employees’ health.

“The biggest challenge we’re facing is the safety and security of our staff and beneficiaries as we continue to move food to where it is needed,” the supply chain chief told this publication.

“We are also looking at how distribution is done, with beneficiaries scattered out – no crowding, no pushing, and no panic.”

“While the scale of the outbreak of COVID-19 is proving challenging, we have experience in working in areas where viruses are active and are using the lessons learnt to ensure we’re responding as efficiently and as effectively as possible.” – WFP Acting Director of Supply Chain, John Crisci

Moving forward, if WFP’s international lines of reaching the hungry and poor are disrupted, it will look to regional and local purchase without disrupting local markets,” he revealed. “We’re looking at every avenue.”

Feeding children left without meals due to COVID-19 in school closures

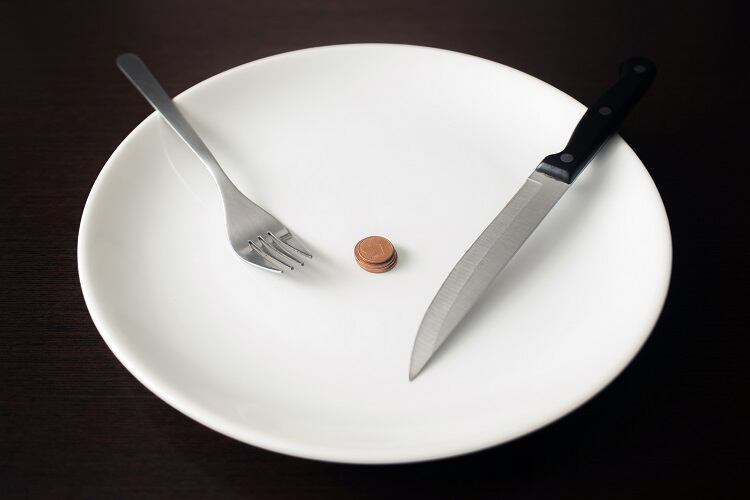

According to the World Food Programme (WFP), more than 320 million children around the world are now missing out on school meals due to school closures associated with coronavirus, or COVID-19.

The UN branch estimates that nearly nine million children are no longer receiving WFP-supported school meals, and that will only increase in the coming weeks and days.

“This pandemic is having a devastating effect on school children around the world, particularly in developing countries,” said Carmen Burbano, director of school feeding at WFP.

“For children with vulnerable households whose only proper meal is the one they get at school, this turn of events is calamitous. We can shift to online learning, but not online eating. Some solutions are needed and that’s what we’re working on.”

In countries where schools are closed, WFP is evaluating possible alternatives, such as providing take-home rations in lieu of the meals, home delivery of food and provision of cash or vouchers.

Further, where emergency safety net programmes are being introduced by governments in response to COVID-10, WFP is advocating that primary school children and their families be included as part of the vulnerable population.