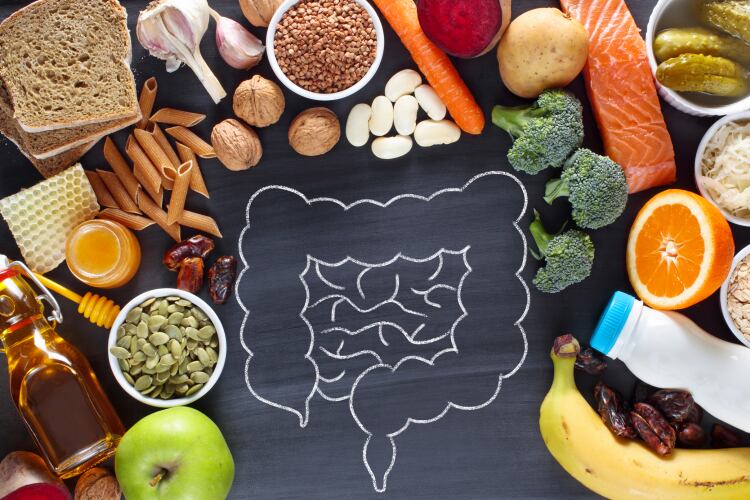

Diet is increasingly understood to have an impact on health and disease, playing a central role in the shaping of the microbiome and contributing to its taxonomic and functional diversity.

“The microbiome has seen a very hot decade. It seems like the microbiome is associated with every part of human biology,” Tim Spector, Co-Founder of ZOE – a start-up that analyses our unique gut, blood fat, and blood sugar responses – observed.

“The microbiome, unlike genetics, is extremely variable between people,” he said last week at the Future Food Tech event in London. We only share about 25% of our gut microbes and the population of the microbiome evolves over time and with changes in the environment, the microbiome expert explained. “It’s not a static thing… This is something people have to look at at different stages of life.”

This is a complex and changeable relationship. But as we develop a deepening understanding of the link between our diets and the health of the microbial communities in our gut (and elsewhere on our bodies), and as links are made between microbial health and our own wellbeing, Spector sees growing potential to move away from generic dietary advice and towards personalised outcomes.

“We’ve only really been able to scratch the surface of what’s possible,” he suggested. Future possibilities include mapping microorganisms in the microbiome and leveraging this data for ‘custom blends’ and ingredient development.

Ravi Sheth, Co-Founder of Kingdom Supercultures, agrees that the combination of larger data sets and machine learning means we are on a tipping point in our understanding of microbiome health.

“As we gather these larger data sets and identify associations, we’ll increase our understanding of what’s healthy for our microbiome and how to achieve it,” he told the food tech audience. “It’s something that’s not going to happen overnight. But in the next decade it’ll happen.”

The ingredients driving healthy outcomes

So, what will this greater understanding of the microbiome, how our diet influences it, and how this links to healthy outcomes mean for the future of food?

At ZOE, a company providing microbiome testing and dietary recommendations, two key health outcomes have been identified as resonating most with consumers and offering greatest short-term potential for development in the space. The first leverages the gut brain axis and relationship between the health of the gut microbiome and mental wellbeing, relaxation and stress management. The second – while perhaps less tangible to a consumer – is the link between the microbiome, immune health and function. “Those are the two places we are seeing the benefit,” Spector explained. “[At ZOE] we work from a customer benefit backwards. That’s what’s going to drive long-term use and adoption.”

Sheth says that the burgeoning understanding of the microbiome and the explosion of interest that has been witnessed in the past decade, has seen certain ingredients emerge as front-runners in gut health research and innovation. “In the last five years people have switched onto fibre, prebiotic foods… but also the new concept of polyphenol-rich food is something that’s taking off,” he suggested.

However, the ingredient expert warned, R&I must reflect the complexity of microbiome science or risk delivering unintended consequences. “Many ingredients in the food system have been developed through a very reductionist approach… Artificial sweeteners were developed with a very specific function in mind… but there are unintended consequences on the microbiome,” he noted.

This warning was echoed by Spector with another cautionary tale. “Inulin, five years ago, was huge. Then these trials come in showing that if you are given more inulin your microbiome diversity drops because you only feed one microbe,” the gut health researcher elaborated. “Fibre is good, it is when you get refined fibre of one type that’s problematic. You need to have the complex fibres you get in real food… Fibre is extremely complex. Microbes will be specific to each type of fibre, not just soluble or insoluble.”

Areas like postbiotics offer ‘great potential’ but ‘it’s early days’ and further research is needed, Spector continued. “Postbiotics is a new term that means the metabolites or chemicals produced by microbes. It is a new and evolving field… we don’t know that giving that product by mouth is the same as the microbe producing it lower in the gut,” he noted.

The importance of testing for personalised nutrition

For personalised approaches to gut health and nutrition to come into their own, Spector believes we need to increase testing across a wider cross section of society. “We’ve got to see [personalisation go] hand-in-hand with microbiome testing as the cost comes down,” he argued.

The data collected can then be used to develop individual microbiome profiles, putting people into categories and providing more targeted products. Rather than true personalisation, Spector believes the future of nutrition will be a more nuanced segmentation.

“It’ll be stratified rather than uniquely personalised,” he predicted, suggesting increased testing, the development of apps and sophisticated digital labelling technology will unlock greater information that consumers will leverage to create their own unique diet plans. “We might have stratified products for young, old, people who know their microbiome group,” he suggested.

However, Spector – who is himself involved in app development – acknowledged some obstacles must be overcome before this vision of the future can become reality. In particular, he said that there is still a question mark over what level of personalisation is feasible in retail.

Sheth highlights another hurdle: production capacity. When we are talking about new innovative ingredients, the difficulty is usually reaching cost-effective scale. In more personalised microbiome ingredients, Sheth believes the problem goes the other way. “Manufacturing has been a really interesting challenge, there is a real lack of infrastructure at the small-to-medium scale [required to deliver more personalised products]. To get to personalisation you need to have small or medium capacity. That’s a big bottleneck to a lot of progress in this space,” he noted.

Personalised nutrition: A luxury for the rich?

Dietary guidelines developed by governments and other bodies aim to deliver the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Personalised nutrition aims to utilise individual host and microbiome variations to generate data-driven personalised dietary recommendations.

But in relying on testing and cutting-edge ingredients, is there a risk that the health benefits of this space are only going to be accessible to the privileged few? Can microbiome science and personalisation deliver population health benefits to the mass market? Or are we likely to see a further polarisation of health outcomes along socio-economic lines if personalised nutrition takes off?

Spector takes a trickle-down approach. “Like any new product you need volume. Once you get volume the price comes down,” he responded. “Everyone can benefit a bit from this knowledge.

“At the moment you have one size fits all… I think we’ll start to see much more stratification because of personalisation.”

Sheth added: “Industry brands can personalise their brands targeting completely distinct [consumer groups] with distinct value propositions.”