Is plant-based meat losing its sizzle? In the US – maybe. There, in the four weeks to October 3, sales of plant-based meat alternatives fell 1.8% on the same period the year before, taking declines for 2021 to 0.6%, according to retail data group SPINS. It said a combination of too much choice and supply issues have hit demand for alternative proteins.

On top of downbeat results from Beyond Meat and Maple Leaf Foods, that’s dampened expectations that the sector has the teeth to take a sizeable bite out of a global meat market predicted to reach a value of over a trillion dollars by 2025.

In Europe, the hard data still points to high single digit year-on-year growth for meat alternatives, said Thijs Geijer, a senior economist covering the food and agriculture sector at Dutch bank ING. In a report last year, he estimated that the market for meat and dairy alternatives in the EU and the UK will be worth €7.5 billion by 2025, up from €4.4 billion in 2019.

After the pandemic helped fuel growth in the nascent category, he expects some flattening once the out-of-home sector makes a more sustained recovery. Nevertheless, he believes “the same drivers are still in place and we haven’t updated our projections so far”.

That said, like SPINS, he too warns of plant-based fatigue setting in. “The novelty is waning off as consumers who are open for it have tried them by now. The market has moved to a situation where all the basics like burgers, nuggets, sausages are pretty much covered with some additions around the edges. I’m not sure whether that’s enough to keep novelty seekers happy. The more innovative stuff is happening in other categories like plant-based cheese and seafood.”

Familiarity breeds contentment and contempt

The problem of potential plant-based meat fatigue is one identified by ingredients company IFF. It says the industry most move on from its fixation with alternatives designed to appropriate the texture, flavour and appearance of real meat. “The industry is doing burger, burgers and more burgers and a nugget here and there as close as the real deal as we can,” a spokesperson said.

Mimicry has succeeded in bringing mass-market, chiefly omnivore consumers to the meat alternatives table. But if the industry wants repurchases and an increased wallet share - not just the ‘try it once out of curiosity’ purchaser - “these consumers expect novel eating experiences”, we were told.

Tellingly, IFF’s consumer research has revealed more than 70% of people are not interested in mimicking. So, what do people want from meat alternatives?

According to IFF, NPD has to walk a fine line between giving consumers experiences that are both novel and still recognizable. Familiarity, after all, breeds both contentment and contempt. The challenge of innovative products is that they need to fit with different eating occasions. That requires both convenience and what IFF would call “a culinary syntax” for faster adoption.

‘It looks like chicken but tastes like a plant’

“People want change, but they don't really like change,” added Sonia Huppert, Global Innovation Marketing Leader for Re-Imagine Protein at IFF.

IFF’s alternative proteins, she explained, are targeting end consumers who are flexitarians and omnivores: people who will continue to eat animal-based products but who just want to eat less of it. Instead of mimicry, therefore, they want new types of foods that will bring them new experiences. Consequently, Huppert’s team is looking to bring a familiarity into something that's totally different in order to increase the penetration of plant-based foods in the daily diet of the consumer.

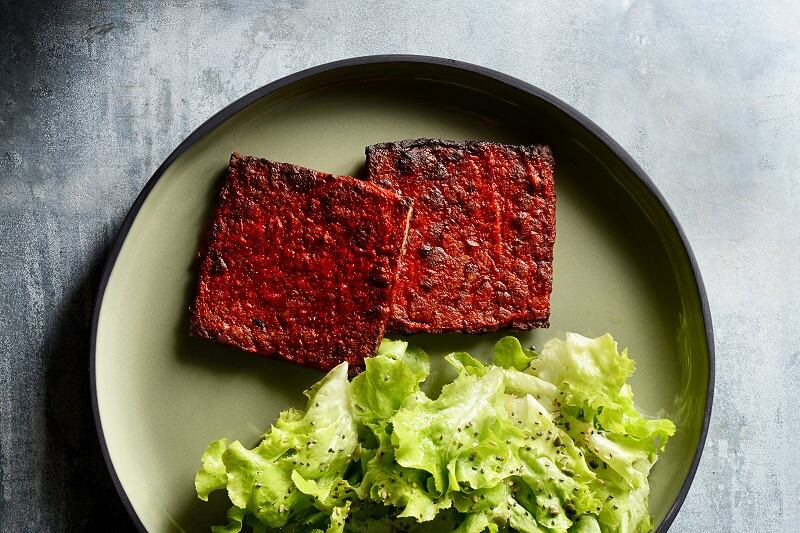

IFF tasked Julien Ferretti, chef at the Institut Paul Bocuse, the Lyon-based International School of Culinary Arts, Hospitality and Food Service, to create original plant-based dishes – not the omnipresent burgers, nuggets or sausages – that go ‘beyond mimicking’. One result is best described as something that looks and feels like a whole cut of meat in appearance and texture, but with an improved vegetable flavour.

“It’s the great result of mixing different plant-protein with different stabilisers,” explained Huppert and “cooked in different ways to get a square block that is very appealing when you look at it but also different in the texture, and with the taste much closer to plants.”

The challenge of how to make vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, beans, cereals, grains palatable to consumers is an age-old one wrestled in particular by parents with small children. Designing meat alternatives that taste like plants, but better, and which can be easily and quickly cooked and prepared may therefore be a masterstroke.

Consumers want a "new type of cuisine where you put plants in the centre of the plate", said Huppert. “The challenges will be to provide protein quantity and plant-based meals that are faster, easier and more convenient to prepare."

Huppert’s IFF team is experimenting with different alternative protein combinations such as soy, pea and canola, to bring different tastes and textures to the table. Soy is a must though, claimed Huppert, as it ticks all the right boxes with regards sustainability, nutrition, supply and availability.

"If you go into the area of non-mimicking, there are endless opportunity,” she added. “It could fill many types of eating occasion.”

What’s more, these types of new products could boast fewer ingredients and be designed based on the nutritional profile and the health benefit that a manufacturer would like to provide. “Because these products are starting from a blank canvass, we're seeing beyond mimicking as the great way of putting nutrition and clean label at the heart of the design."

The principle can also be applied to drinks, she said. The plant-based drink sector has a higher penetration rate (around 10-15% depending on the market) than meat alternatives. "But to go higher it needs to have better mimicking of animal-based products or go into a direction where you provide a different profile to the consumers and put nutrition at the heart of the product formulation." This could mean, for example, “breakfast shots with high amounts of protein, different vitamins and minerals and a plant-type taste. The colours could be those of the plant inside instead of trying to mimic milk.”

‘Let’s umamify plant-based’

What else needs to be at the heart of the next generation of plant-based meat and dairy alternatives? Umami is one of the first tastes we are exposed to: because breast milk contains glutamate. As a result, we have an almost innate craving for it, explained IFF Senior Savory Flavourist Roberto Faria.

Building this craving into plant-based design therefore calls for umami, he said. “Umami in plant-based is very much needed because meat in general contains natural umami compounds such as glutamate and nucleotides, which are highly important to activate your taste receptors and therefore make the product more pleasant for you to eat. So if you're trying to replicate the food taste of dairy or meat products, we need to add umami.”

There are two routes to better “umamify the plant-based category” and pioneer the savoury plant-based products of the future, he told us. One is combining technologies into an umami modulator (IFF has been working with umami modulation for several years) that delivers umami taste as well as stimulate a mouth-watering, mouth coating or rich lingering aftertaste. The other is using fermentation of the plant protein in order to “liberate the inherent amino acids for them to deliver umami taste”, said Faria.

“Mouthfeel is very important in plant based because it tends to be dry and without the natural juiciness – that's why we need to combine the umami with other technology that make it easier for consumers to taste it, to swallow and not have that aftertaste you get from vegetable proteins.”

Fat also key

Fat, too, is critical in IFF’s efforts to beef up plant-based meat alternatives. If umami is the fifth taste, fat could be the sixth. A study by IFF Sensory Scientist Camilla Arndal Andersen (who dropped tiny amounts of skimmed, semi-skimmed and full-fat milk onto the tongues of 24 participants) has claimed, for example, to show that the brain knows when the tongue traces fat.

"Fat is a huge delivery system for the taste in the plant-based sector,” said IFF Principal Technologist Re-Imagine Protein Alex Lamm. “The meat-mimicking part has been tackled by different texturised proteins and ingredients,” he told us. “Now it's time to look at the next step, which is the fat. If you think about a nice tasty steak, the fat is bringing the taste. The fat is transporting the meat flavour, the mouthfeel, the creaminess and the lipstick effect of a fatty meat profile.”

Plant-based formulators therefore face a complex task to develop fat that behaves most like animal fat. It needs to give a similar succulence, texture and visual appearance, whilst also remaining stable in the plant protein product. “The first challenge is thinking where the fat comes from,” elaborated Lamm. “Is it back fat? Muscle fat? It's really important because these areas have different melting points.”

The answer is ‘smart’ fat, made up of a combination of plant-based fat materials (such as coconut, vegetable or algae-based) which have different attributes and melting points. This hopes to solve the problem of, for example, a vegetable fat melting out of a product during cooking and becoming dry.

Hybrid fats, combining different animal, plant and even the realms of cultured fat, could be a further potential solution for next-generation plant-based producers. After all, these products are targeting omnivores seeking to cut their meat consumption, so they are likely to accept some animal element in their meat alternatives. Hybrid fat combinations bring other possible benefits such as reducing the cost of a meat-based recipe or improving nutritional profile.

“Producers are looking into finding new scopes of products that aren't mimicking meat in the future,” suggested Lamm. “So maybe using hybrid fats could be a kind of door opener for a new food which is not trying to copy something but there as a standalone to be something different.”