Supermarket retailers’ depleted shelves have made headlines in recent weeks as consumers ‘panic buy’ canned goods, rice, pasta, and toilet paper.

This unprecedented boost in demand comes as coronavirus, or COVID-19, spreads across the UK. As of 21 March, 5,018 cases have been reported, and 233 people have died.

Retailers, who are ‘working incredibly hard’ to keep shelves stocked during the outbreak, have urged consumers to ‘be considerate’ in the way they shop.

“We are working closely with Government and our suppliers to keep food moving quickly through the system and making more deliveries to our stores to ensure our shelves are stocked,” noted Helen Dickinson, Chief Executive of the British Retail Consortium.

Indeed, late last week the Government announced plans to relax competition laws to enable supermarket retailers to share data with each other on stock levels, cooperate to keep shops open, ‘pool staff, share distribution depots and delivery bans, and extend drivers’ hours.

Addressing consumers, the retailers continued: “We understand your concerns, but buying more than is needed can sometimes mean that others will be left without. There is enough for everyone if we work together.”

Professor Tim Lang, however, believes the Government could be doing more to ensure supply of healthy foods amid the outbreak.

Taking to Twitter, the Professor of Food Policy at City, University of London, wrote: “We urgently need a national scheme of rationing based on nutritional guidance not ad hoc led by retailers. It’s not their fault. It’s Govt’s job.”

Food rationing

Together with Emeritus Professor of Science Policy at the University of Sussex, Erik Millstone, and Professor and Director of the Sustainable Places Research Institute at Cardiff University, Terry Marsden, Professor Lang has penned a letter to UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

As ‘academics with experience in food policy matters’, the trio is calling on the Government to initiate a health-based food rationing scheme during the crisis.

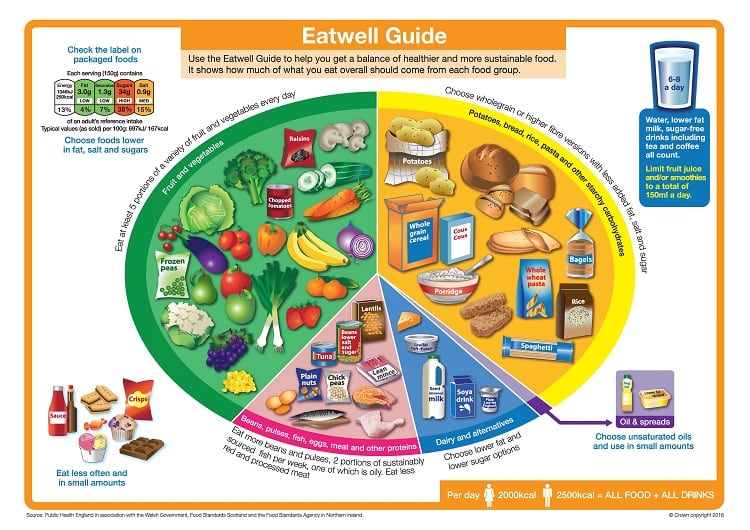

“This should start from Public Health England’s (PHE) Eatwell Plate, our official nutritional guidelines, and draw on expertise from the devolved administrations, and relevant disciplines,” they noted.

The Eatwell Plate, or Eatwell Guide, is based on the main food groups PHE says make up a healthy diet. These food groups include: potatoes, bread rice, pasta and other starchy carbohydrates; fruit and vegetables; dairy and alternatives; beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins; and oils and spreads.

The new Food Rationing Scheme – designed to be equitable and based on health needs – should be opened immediately, the academics continued. The scheme must take age, income, and vulnerability into account, and be applied UK-wide.

Prioritising people on low incomes

Professors Lang, Millstone, and Marsden have also drawn the Prime Minister’s attention to people on low incomes, who they say are ‘particularly anxious’ about food insecurity during this crisis.

In the UK, more than 8.4m people are characterised as ‘food-insecure’. And diet, according to London-based not-for-profit the Health Foundation, is a key factor in lowering life-expectancy for the poorest people and weakening their immune system.

Yet, in the midst of this crisis, food banks are closing. Those that remain open have supply shortages and ‘rocketing demands’. “Some very hungry people are being ‘gate-kept’ out of food banks because systems for allocating vouchers are failing,” the academics continued.

“Food banks do not and cannot resolve structural inequalities, income deficits, or lack of access. The current crisis is in danger of aggravating existing problems.”

It is not supermarket retailers’ responsibility to ration for health or ‘filter food purchasing according to need’. The academics are urging the Government to rapidly review options for ensuring people on low incomes have sufficient money to ‘buy a decent diet’.

This could come in the form of cash injections for those receiving welfare benefit, or as a national voucher scheme redeemable for ‘nutritionally sound’ purchases such as fruit and vegetables.

Improving food supply messaging

Professor Lang and his peers also suggested that stockpiling food could have, at least in part, been avoided by clearer messaging from the Government.

Raising concerns that “public messaging about food supply is weak and unconvincing”, the cohort stated that ‘more consumer-friendly messaging’ could have produced different results.

“There is already a dangerous tendency to blame consumer behaviour not shape it. Nudge thinking is no longer sufficient. Consumers have repeatedly been told to look after themselves, so cannot be blamed for acting within their viable realm of influence.

“It might be regrettable, but stockpiling or uncivil behaviour in stores are signs that appeals to restraint or repetition of the ‘We are in it together’ message are thin when it comes to food supply.”