Adulteration, tampering or misdescription? Nofima defines food fraud

Food fraud, or food crime, is a wide-ranging subject that “can mean many things”, according to the Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research (Nofima).

A European initiative led by senior scientist Petter Olsen at Nofima has responded to the need for clear definitions across the bloc: “How does one define ‘food fraud’ and sub-terms such as ‘mislabelling’ or ‘adulteration’?” asked Olsen when we caught up last week.

Currently, a number of different definitions exist for food fraud. “We saw the need for one document, where all these definitions are internally consistent,” he said.

Together with food fraud experts from several European countries, Olsen has defined many of the English terms and concepts used in connection with food fraud for the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN).

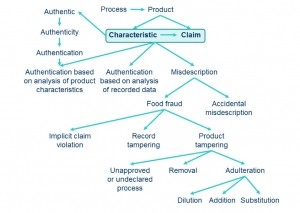

The resulting document, titled ‘CWA 17369:2019 – ‘Authenticity and fraud in the feed and food chain – Concepts, terms, and definitions’ employs a hierarchical system designed to make it easy to understand not only individual definitions, but how the words relate to each other.

“We wanted to make a clear hierarchy, a clear ordering, and define very clearly the relationship between terms – just only the individual definitions themselves" - Petter Olsen, senior scientist, Nofima

The definitions will and can be used by anyone who deals with, or needs refer to, food fraud, Olsen told us. “Especially in the context where the meaning of words is really important, for instance when writing legislation or scientific articles.”

More generally, the definitions will also serve those who wish to have an informed or structured communication on food fraud, he said.

While at this stage the standardisation is voluntary, it will be used to inform more formal standardisation processes – some of which will end up in mandatory standards, Olsen continued.

When the document launched last month, it was distributed by national standardisation bodies in Norway, Estonia and the Netherlands, “but we know that several other countries are also going to make these standards available on their respective websites.”

Food fraud or food safety?

Another key driver for establishing standardised definitions relates to the two words leading the hierarchical mapping: characteristic and claim. ‘Characteristic’ relates to the food product itself and ‘claim’ refers to a product’s documentation.

“This is something that has been largely missing in the food fraud discussion, because so much of the food fraud discussion is dominated by people who have a food safety perspective,” said Olsen.

Indeed, food fraud does not only refer to the physical content of a product, he explained. It is also the description of it, whether it be the label or accompanying documentation.

“The realisation that you can commit food fraud without touching the product at all, that you just need to fiddle with the documentation. That was missing in many of the discussions and definitions.”

According to Olsen, not only is there confusion in its definition, but many national authorities fail to penalise when food fraud occurs – particularly when there is no food safety issue.

“[Authorities] will really investigate and give priority to cases where there might be a food safety issue. There are exceptions to this, but in many countries, the food fraud realm has grown from the food safety realm.”

One widely publicised example of food fraud was the ‘Horsegate’ scandal – whereby horsemeat was identified in prepared frozen and meat products that were said to contain beef. “There was absolutely no food safety issue with this. You couldn’t get sick from eating the lasagne that contained the horsemeat.”

Less publicised, however, is fraud in the captured fish market.

“Somewhere between 15% and 30% of all captured fish in the world is illegally caught and landed. Either because vessels go out fishing in the night and come back in without lights, land, and don not report anything, or because legal vessels land [for example] 1,500 kg [of fish] and just write down 1000 kg,” Olsen told this publication.

“There is a significant amount of fraud going on when you land captured fish. It’s still a billion-pound industry.”