LCA methodology criticised for simplistic approach to organic production

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a technique for assessing the environmental aspects associated with a product over its life cycle.

From cradle to grave, LCA addresses the extraction of raw materials associated with the product, as well as its production and distribution of energy throughout its use, reuse, and final disposal.

LCA is the method most widely used to assess environmental impacts of agricultural products. However, according to a team of international researchers, current LCA methodology misrepresents less intensive agroecological systems such as organic agriculture.

The French, Swedish and Danish colleagues from the French National Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) are calling on LCA practitioners for change.

Neglecting environmental issues

Interest in sustainable agriculture and food production is on the rise. From farmers to policymakers and media professionals, stakeholders are increasingly comparing different products to determine where they stand in terms of environmental sustainability.

Despite being a popular way of comparing such products, LCA methodology can sometimes claim that organic agriculture is actually worse for the climate than conventional agriculture.

According to the INRAE researchers, this is because current LCA methodology misses many of the major benefits of organic farming.

LCA studies of agriculture and food systems rarely consider important issues such as land degradation, biodiversity losses, and pesticide effects, the researchers argue in Nature Sustainability.

“Despite efforts over the last 15 years to improve assessment of impacts due to land use, soil properties and functions remain little represented in LCA,” they note.

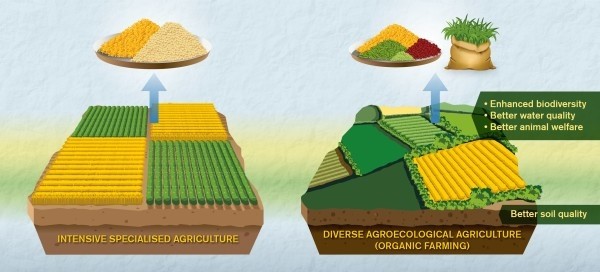

In most agri-food LCA studies, the benefits of organic farming practices, such as diversifying crop rotations, are ‘largely ignored’. “Consequently, current LCA studies rarely capture positive characteristics of these practices that are core elements of organic agriculture.”

Further, the authors criticise LCA studies for ‘rarely considering’ the negative impacts that pesticides can have on humans and ecosystems, as well as for ‘tending to ignore’ biodiversity impacts.

“Meta-analysis of many field observations have shown that organic agriculture supports biodiversity levels, measured as species richness, that are approximately 30% higher than those of conventional agriculture, a result that has remained robust over the last 30 years,” the authors write.

“Even future LCA studies are unlikely to capture such large differences due to agricultural practices, as the method selected by the LCA community to assess impacts on biodiversity (potential species loss from land use) is recommended only for identifying hotspots within product systems, not for comparing products or production systems.

“This model thus cannot be used to distinguish conventional and organic agriculture.”

Importantly, the INRAE colleagues describe LCA methodology as having a ‘narrow perspective on functions of agriculture’, because impacts are quantified and reported per kilogram of product.

In intensive, conventional systems, impacts may be lower per kilogram of product, while having higher impacts per hectare of land. Yet this greater impact per hectare will not be communicated in an LCA study.

Recommendations for LCA practitioners

The researchers have therefore called on LCA practitioners to improve the methodology and integrate it with other environmental assessment methods to get a more balanced picture.

Recommendations include assessing land degradation, biodiversity, and pesticide effects; using both product-based and area-based functional units; and considering farm practices and local soil, climate and ecosystem characteristics in detail.

“Environmental assessment of agricultural systems must adopt a broader perspective, consider negative impacts of pesticides and consider effects of agricultural practices on soil health and biodiversity,” according to the researchers.

“In addition, more research is needed to allow for meaningful modelling of indirect land-use change and other indirect effects.”

Source: Nature Sustainability

'Towards better representation of organic agriculture in life cycle assessment'

Published 16 March 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0489-6

Authors: Hayo M. G. van der Werf, Marie Trydeman Knudsen, and Christen Cederberg