Will the EUDR happen after all – key summary

- European Parliament debates a possible one-year postponement of EUDR implementation

- Delay proposal includes review clause allowing further regulatory simplifications later

- Member states remain divided with Germany backing delay and France opposing

- Industry leaders like Ferrero and Nestlé warn delay risks compliance investments

- Grace period seen as preferred option to reduce uncertainty and maintain progress

Just when you think that the delays, alterations and simplifications to the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) have ended, everything is up in the air again!

Lawmakers and stakeholders in the European Parliament are once again intently discussing the potential of a year-long postponement of the landmark regulation.

Despite an earlier proposal that partially assuaged fears of a delay, many member states are still pushing for one.

The delay would not only postpone the regulation for a further year, but may also include a review clause, meaning that it could be opened up again for further simplifications.

This is despite opposition from many key industry stakeholders, who suggest that a further delay would create uncertainty and discredit their compliance efforts.

The EUDR so far

The EUDR has a long, complicated history, with more twists and turns than an Agatha Christie novel.

What is the EUDR?

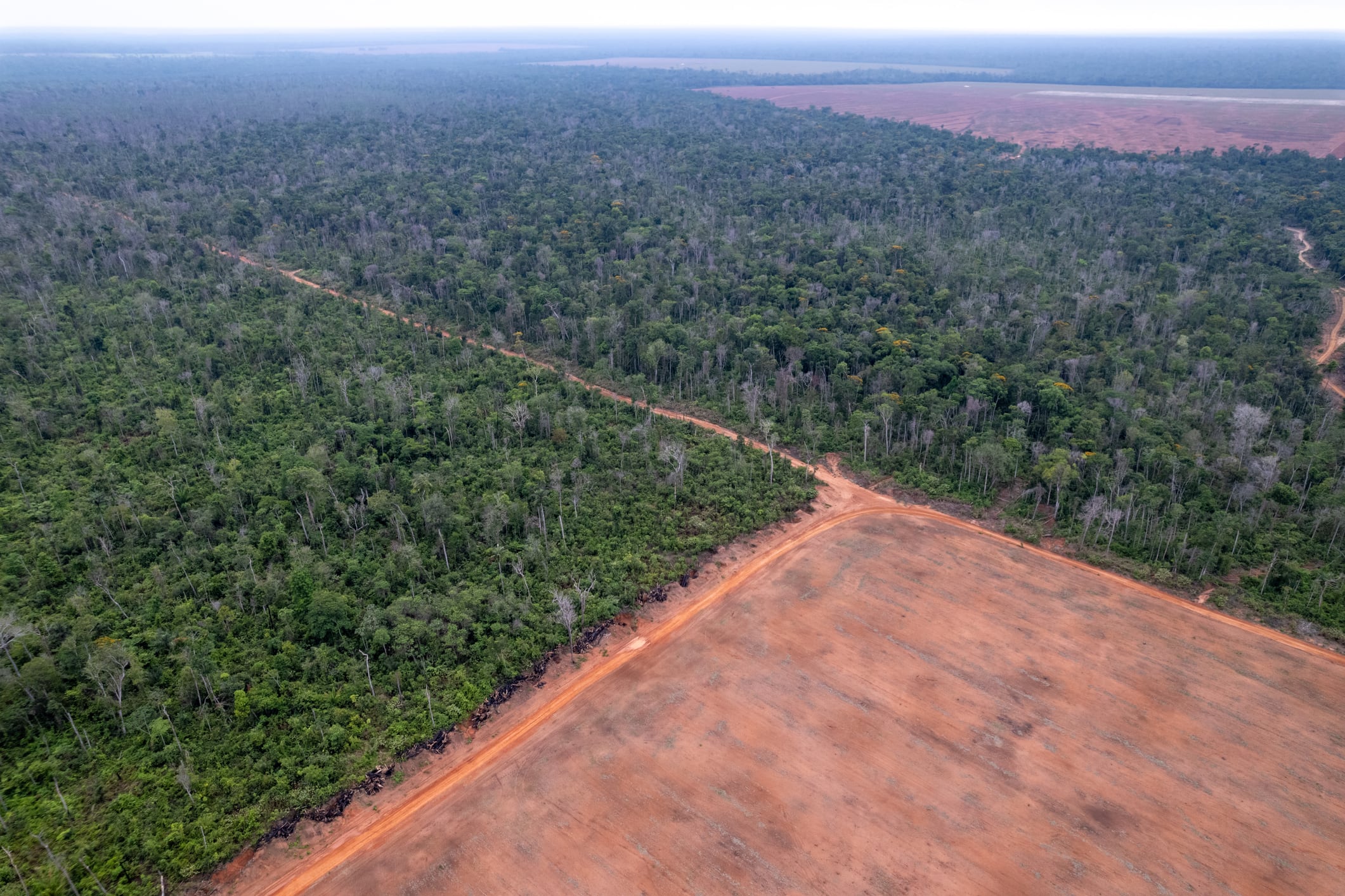

The European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) is a regulation aiming to reduce the use of deforestation-linked commodities within the EU. It covers seven commodities – cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soy, wood, cattle, and rubber.

To comply, companies placing these commodities on the EU market must be able to trace them back to their source, and prove that they are not linked to deforestation taking place after the cut-off date of December 31 2020.

After it was initially proposed in 2022, the regulation had been slated to come into force by 30 December 2024.

With only a few months still to go, however, it was pushed forward by a year, with the Commission suggesting that businesses simply weren’t ready. This delay was voted through Parliament in late 2024.

A proposal for a second year-long delay followed this in September of this year. The Commission this time suggested that the IT system wasn’t ready for the burden that the onrush of complying businesses would bring. This delay remains a proposal for now – although something similar could soon become reality.

Not long afterwards, the Commission made a new proposal – namely, that the delay would only apply to smaller operators, their deadline would be pushed forward by only six months rather than a year, and that for larger companies, a six-month grace period would be implemented instead. This grace period would mean penalties for non-compliance would temporarily be less severe.

This proposal also came with additional simplifications, such as the removal of the requirement for downstream operators to submit due diligence statements. Downstream operators are operators trading in a relevant commodity after it was placed on the EU market.

Phew. That’s a lot of changes. But it’s not over yet. Depending on what Parliament, the Commission and member states agree, another year-long delay could still be on the cards.

Could the delay go ahead after all?

Many in the European Parliament are unhappy with the regulation as it stands.

The Danish presidency of the EU Council proposed replacing the grace period with a year-long delay. This was shot down because, although it kept the suggested simplifications in place, it stopped short of introducing new ones.

Now, lawmakers are debating whether to vote through the one-year delay after all, but with a review clause attached. This review clause would allow the legislation to be reopened and, potentially, further simplifications to be added.

The member states are split into three blocs, explains Pierre-Jean Sol Brasier, strategic communications advisor at NGO Fern.

Firstly, strong critics of the EUDR include Sweden, Hungary, Austria, and the Baltic states. These countries are asking for further simplifications from a review clause. The latest country to back a full-year delay is Germany.

The EUDR’s “champions” include France, Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands. These countries are currently more resistant to calls for a delay.

Other member states, including Italy and Greece, are somewhere in the middle. However, suggests Brasier, they may be moving towards backing a review clause.

The Commission itself has made it clear that it does not want any further simplifications. The Denmark presidency is working on a compromise.

On Wednesday, member states will agree on their positions, explains Brasier. The European Parliament will vote on its position next week, during the plenary session in Strasbourg. After this, there will be an opportunity for the Commission, Parliament and member states to discuss the regulation again. The final decision will be made at a further plenary in December.

How has industry reacted?

Several key voices in industry have spoken out against a further year-long delay, suggesting that a grace period would be a better option for creating clarity and stability.

Industry has invested millions into EUDR compliance, explains Francesco Tramontin, VP for group public policy at Ferrero. A year-long delay would be “incredibly impactful, in a negative way,” and would put these investments into question.

Ferrero has invested into EUDR compliance “in good faith, because we thought there was a sense of direction. Now it’s being questioned.”

Nestlé is also against the delay. It is extremely important that the work already done for compliance is preserved, says Bart Vandewaetere, VP for corporate communications and government affairs at Nestlé.

By contrast, those who are not ready have an incentive to continue pushing the regulation back. “Next year, the laggards will have another excuse”.

Instead, he suggests that the due diligence procedures should be simplified, to ease the amount of data that the EUDR’s IT system must handle. He also suggests that the grace period should be extended to 12 months.

A further delay would lead to much greater legal and market uncertainty, adds Victoire de Werve, global lead for sustainability policy at agribusiness company Olam Agri.

The company also sees the risk of stakeholder disengagement on the ground, where stakeholders have been preparing for the regulation.

The changes being made to the EUDR are indeed hurting its credibility on the ground, agrees Juliette Cody, climate and nature lead at Barry Callebaut, the world’s biggest chocolate supplier.

The proposed grace period would help companies learn to become familiar with the due diligence provisions and operationalise the necessary checks, suggested Olam Agri’s de Werve, as well as find out what changes they need to make in the future.

The grace period is best for those who are already prepared and have the “fundamentals” of compliance, suggests Ferrero’s Tramontin. For these opporators, the grace period allows them to finetune their compliance.

Meanwhile, for those who are not prepared, a grace period would make their lack of preparation more visible to the authorities.

Whether the industry will sway lawmakers is uncertain, and only time will tell. What is known, is that with less than two months until deadline, businesses are in desperate need of clarity.