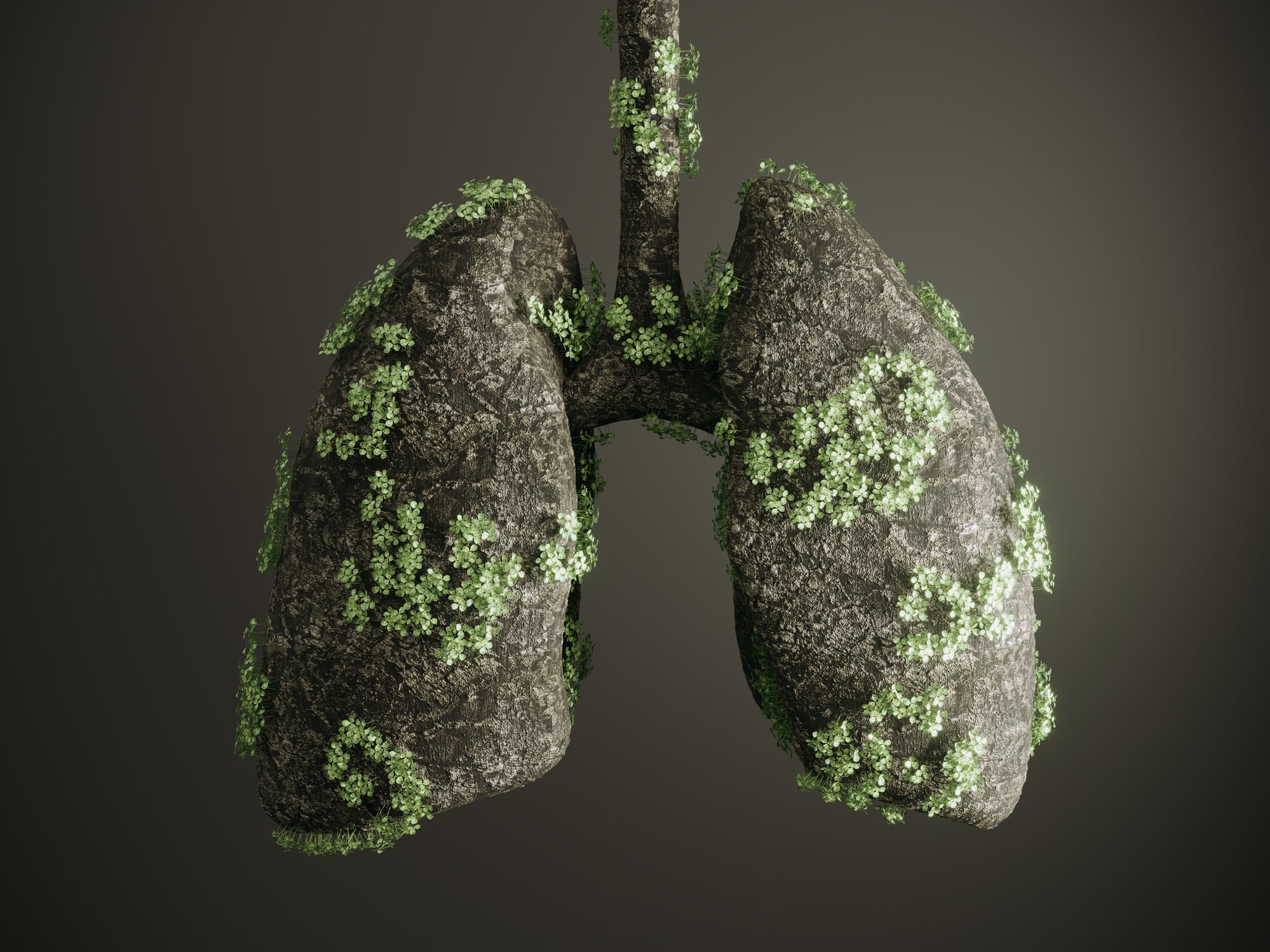

The Amazon Rainforest, which stretches across Brazil and has sections in Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, is the largest forest on Earth. Containing around 10% of the world’s species, it is often nicknamed the ‘lungs of the world’ because of its role in regulating the climate.

It has also long been threatened by deforestation, driven by the large-scale production of, most prominently, soybean and livestock.

While this threat has never gone away – most countries containing the Amazon are rated at ‘standard risk’ of deforestation in the upcoming EUDR – it was at least somewhat mitigated by the Amazon Soy Moratorium, agreed in 2008.

Now, the moratorium is under threat. If repealed, safeguards against deforestation could be dramatically reduced.

What is the Amazon Soy Moratorium?

The Amazon Soy Moratorium is a voluntary sectoral agreement whereby commodity traders in the soy sector agree to avoid buying soybeans from areas of the Amazon deforested after 2008.

It’s scope covers only the Brazilian Amazon, although this in itself means around 60% of the overall forest.

Until 2016, the agreement was renewed every one or two years, after which it was put in place “indefinitely.”

Most people believe, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), that it has been successful in reducing deforestation in the Amazon.

The moratorium is not just an agreement, but is backed up by flyovers and satellite data to keep track of the amount of deforestation taking place, explains Jonathan Gorman, technical director of the environmental services company Efeca.

Since it was developed, the moratorium has prevented the conversion of more than 1.8 million hectares of the Amazon, according to the UK Soy Manifesto, an industry association aiming to reduce conversion and deforestation in the soy sector. Currently, around 98% of soy grown in the Amazon biome is moratorium-compliant.

Between 2006 and 2019, the area of soy cultivation went from 1.6mha to 4.7mha, according to the UK Soy Manifesto, mainly on land that was deforested before the moratorium’s cut-off date. It suggests that 1.7m compliant hectares still remain as potential land for soy cultivation .

Why could the moratorium collapse?

While it is far from confirmed, a number of recent developments suggest that the moratorium’s days could be numbered.

Underlying the opposition to the moratorium is that it is quite different from national anti-deforestation laws. Unlike legislation, such as Brazil’s Forest Code, the moratorium prevents farmers from deforesting their own land.

“The tension has always been that it goes beyond legal requirements,” explains Gorman.

Thus, there is significant opposition to the moratorium.

Now, things have begun to change. Legislation from the state of Mato Grosso, in central-west Brazil, has released legislation that removes tax incentives for soy companies that comply with the Amazon Soy Moratorium, effectively making their activities more expensive. According to Gorman, the legislation was inspired in part by concerns from farmers.

“This one is local state legislation, but it is designed to disincentivise shippers from stipulating or requiring the Amazon soy moratorium requirements,” Gorman explains.

Mato Grosso’s legislation was put in place after the decision of Brazil’s supreme court to lift its suspension on the bill.

Beyond this, Gorman says, other activities within Brazil have suggested that discontent with the moratorium is growing.

There has been significant opposition from manufacturers themselves to the potential of the moratorium being weakened. The UK Soy Manifesto, which includes more than 50 businesses representing over 60% of the UK’s demand for soy, has reaffirmed its support for the moratorium.

As customers of the soy in question, Gorman believes, the 50 businesses’ support for the moratorium should create a strong incentive to keep it in place.