What’s covered in Switzerland’s new animal welfare labelling law?

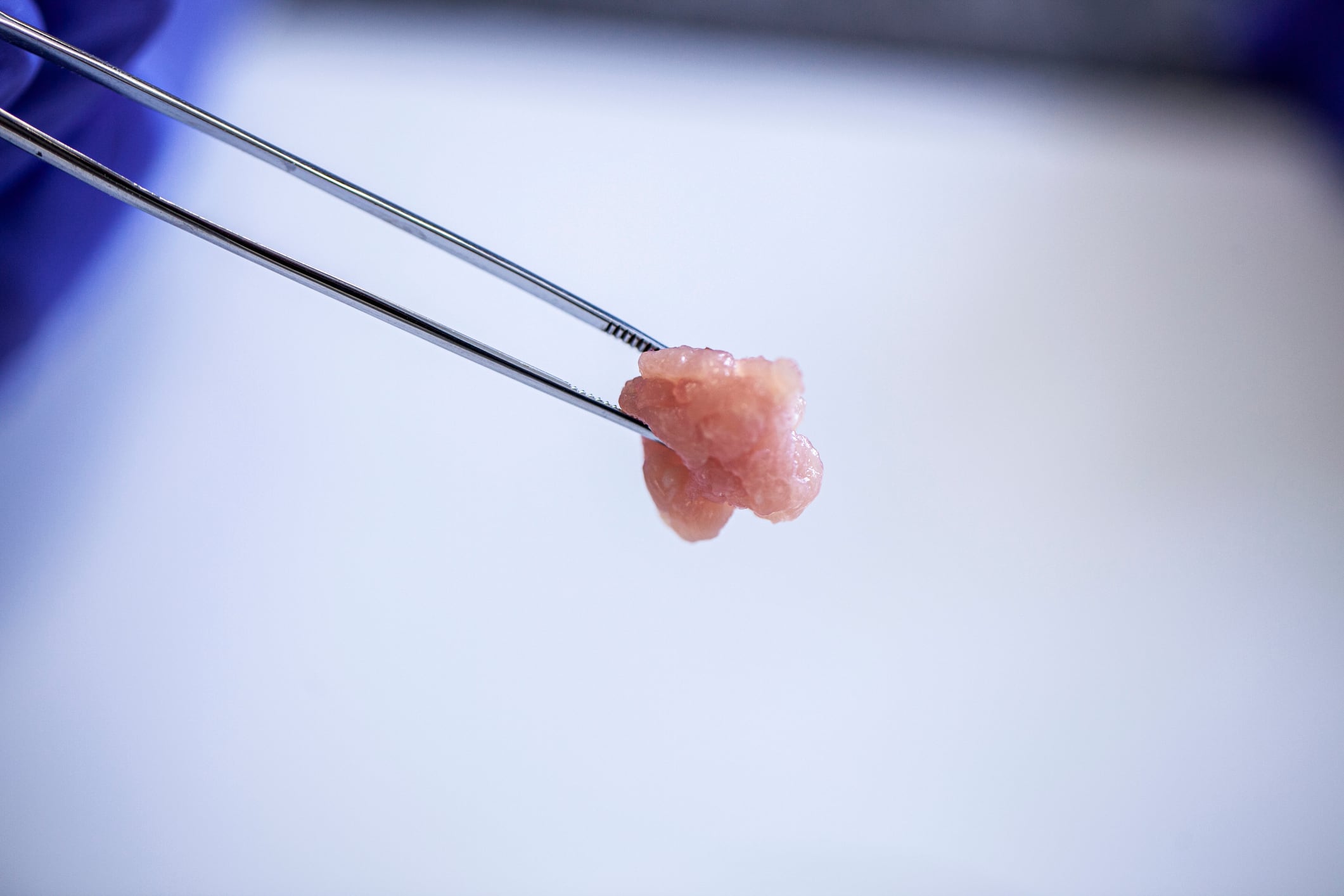

All food products of animal origin must be labelled clearly if they’re made using painful procedures without anaesthesia or stunning, including:

- Cattle (beef and milk): Castration or dehorning without anaesthesia

- Pigs/pork: Castration, tail docking, or teeth clipping without pain relief

- Chickens (meat and eggs): Beak clipping without anesthesia

- Cows: Dehorning without pain relief

- Frogs: Leg removal without anaesthesia

- Foie gras: Liver from force-fed ducks or geese (force-feeding is banned in Switzerland but still occurs in imports)

The new rules enforced this month aim to increase transparency for consumers and support Swiss farmers who follow some of the world’s strictest animal welfare rules, according to Switzerland’s Federal Council.

Meat, eggs and dairy from animals that have undergone painful procedures without pain relief as part of farming and food production processes must now be clearly labelled as such.

Legislation will impact both local and imported producers, meaning manufacturers supplying into the country will be required to comply with the new labelling rules within the two-year transition period.

Farming and food industry bodies have levelled criticism at the move, with some organisations claiming it would add “significant” pressure on industries, while also risking the stigmatisation of foreign products made using different welfare regulations.

Retailers and importers have also raised concerns and frustrations over the new rules, including difficulty in tracing the exact rearing conditions of animals.

Will consumers understand the welfare labels?

Also, self-monitoring requirements for smaller businesses and restaurants placed too much responsibility on already stretched resources.

Another criticism was consumers could be at risk of experiencing fatigue or confusion due to the growing complexity of food labelling systems. Recent research suggests that the effectiveness of the new animal welfare label could be limited if it fails to clearly communicate its purpose or value.

This follows a report from the Swiss collective Faire Märkte Schweiz, which revealed nearly a third of so-called sustainable labels did not address fair trade or equitable commercial practices. As such, concerns have been raised that the new animal welfare labelling could similarly fall short in delivering meaningful transparency, potentially undermining consumer trust and the intended impact of the reform.

However, the law change has been welcomed by many, particularly animal rights organisations and charities, including the Animal Charity Evaluators, which said “Switzerland has raised the bar for animal welfare” with the new legislation.

“The introduction of transparent labels in Switzerland is an important turning point,” says Stefania Caiafa, president of META, Milan’s Ethical Movement for the Protection of Animals and the Environment.

It is hoped other countries follow Switzerland’s move

Such labels would allow those not adequately informed about animal production processes to see “what is hidden behind products of animal origin”, allowing consumers to be “free to choose” with “full awareness”, she claimed.

The new rules could influence similar labelling policy changes within the European Union, with Caifa adding: “I hope that transparent labels can be an example for Italy.”

Although Switzerland’s new animal welfare labelling law signals progress on transparency, a recent court ruling has muddied the waters for the country’s meat alternative movement.

Switzerland’s top court banned plant-based producers from using terms like “chicken” or “beef” on meat alternative packaging, claiming it can confuse consumers.

Critics, however, argue the move does the opposite and clashes with Switzerland’s own push for more plant-based diets, as well as adding unnecessary complexity to food labelling.