In a new study published in Appetite, Anja Weber from HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management in Germany has sought to examine the impact of providing eco-score information via smartphone for different food categories.

Further, acknowledging how easily consumers can be ‘overloaded by information’, the researcher has tested just how much information shoppers require.

Basic vs extended food labels

Increasing attention is paid to the environmental impact of food production. Looking at the numbers, the agri-food system is responsible for a quarter of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with food accounting for 50-70% of household impacts on land and water resources.

It would make sense, therefore, that by opting for more sustainable food products, consumers could contribute greatly to the mitigation of climate change.

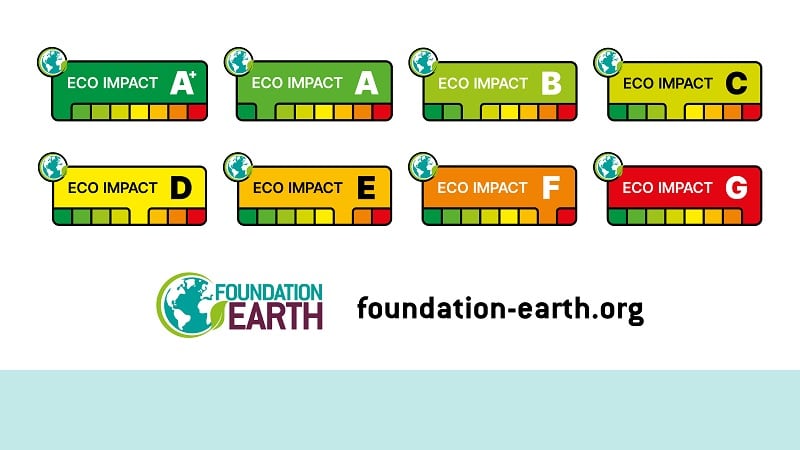

One way that consumers can be encouraged to make more sustainable food choices is via eco labelling, such as carbon labels. Examples of these include Eco-Score and Foundation Earth’s front-of-pack score.

Other eco labels, such as sustainability labels with aggregated scores, can also help consumers check the environmental impact of products before they buy.

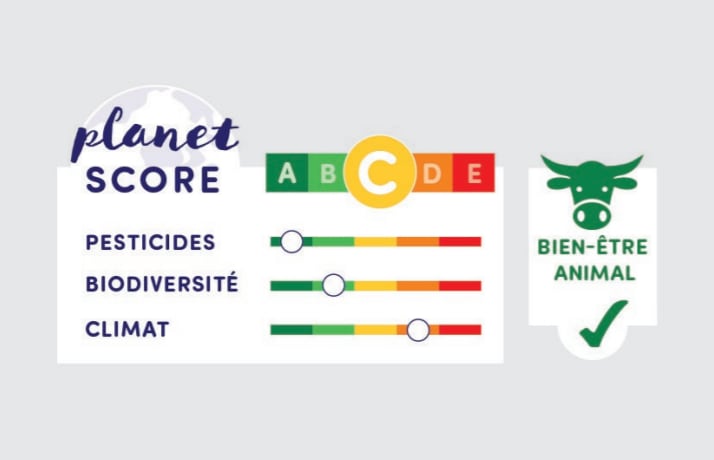

The French-designed Planet-Score is one such example, which like Eco-Score and Foundation Earth’s labels, is based on life cycle assessment (LCA) methodology. However, it also addresses other elements associated with sustainability, notably: pesticides, climate, biodiversity, and animal welfare.

Despite increasing proliferation of front-of-pack (FOP) eco labels in the sector, Weber is unconvinced consumers make use of such labels while food shopping. Smartphone applications, therefore, represent another opportunity to influence consumers’ purchase decisions.

Spotlight on milk, apples, and eggs

Using a mobile survey, designed to simulate the use of a mobile app that conveys additional sustainability information and allows for production comparison, Weber asked 332 German consumers to make fictive purchase decisions for three food categories: milk, apple juice, and eggs.

Participants were placed into three groups: those using basic ranking (in the vein of Eco-Score or Foundation Earth), those using extended eco-ranking (in the vein of Planet-Score), and a control group.

The groups first browsed the product information with eco-ranking, selected one product, and rated their decision uncertainty. To simulate a realistic retailer setting, participants were asked to select from 11 types of milk, 14 apple juices, and nine types of eggs.

Information concerning the eco-ranking of each product was colour-coded from green to red. Those in the extended eco-ranking group received a link to a browser-based smartphone app that displayed a detailed overview of each products eco-ranking and key metrics, such as transportation distance and type of certification.

Findings revealed that participants evaluated the value of the basic and extended eco-ranking quite similarly. However, those in the basic eco-ranking group felt more confident across all categories in their purchase decision.

“In contrast, the extended eco-ranking group remained at similar levels as the control group,” noted Weber.

Concerning label effects on sustainable product choice, each category included two products with the top sustainability score. Around one-third of participants in the control group opted for one of the most sustainable products. In the two eco-ranking groups, up to 65% of participants selected one of the top products.

‘More information is not always better’

According to Weber’s findings, both basic and extended eco-rankings had a positive affect on consumers’ sustainable product choices. More specifically, the basic eco-ranking led to a 26% increase in sustainable purchase decisions. The extended eco-ranking, on the other hand, was found to increase the likelihood of choosing a top-rated sustainable product by 17%.

“Our research supports the idea that aggregated eco-rankings presented via mobile devices, which inform consumers about food’s environmental impact, are an effective means to increase sustainable food choices,” noted Weber.

However, consumers felt more confident in their decision making if a simple decision criterion – as exemplified by the basic eco label – is presented. “The basic eco-ranking based on a single indicator significantly reduced decision uncertainty, while the extended eco-ranking did not boost consumers’ confidence.”

As both basic and extended eco-ranking were perceived as ‘equally credible’ by participants, Weber suggested a basic eco-ranking could be sufficient within the food sector. “The extended eco-ranking also had no advantage over the basic eco-ranking in shifting consumers towards sustainable products.” Thus, Weber continued, ‘more information is not always better’.

Given these findings, the researchers argued there is an ‘urgent need’ to give consumers a better orientation to increase sustainable consumption.

So what does this mean for food retailers and policy makers? Weber recommends the use of eco-rankings, but stressed that excessive information and inconsistencies should be avoided.

“Thus, it is recommended to aggregate information to one indicator, such as the overall environmental impact, which is easily comparable and understandable.”

Journal: Appetite

‘Mobile apps as a sustainable shopping guide: The effect of eco-score rankings on sustainable food choice’

Published online 3 August 2021

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105616

Author: Anja Weber