2019 saw the food industry rise up the agenda and gain further traction in mainstream discourse. Here's our round-up of the top five most shared stories for the year. What were you shouting about? And what will remain in the spotlight for 2020?

Pic: iStock/zakokor

2019 saw the food industry rise up the agenda and gain further traction in mainstream discourse. Here's our round-up of the top five most shared stories for the year. What were you shouting? And what will remain in the spotlight for 2020?

Pic: iStock/zakokor

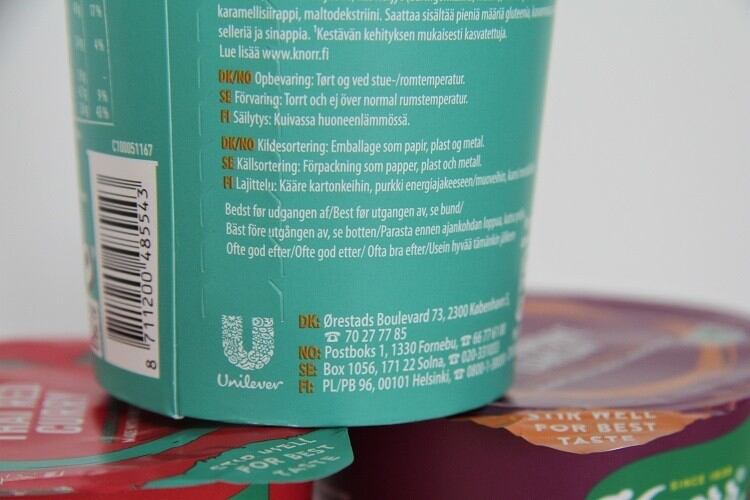

This story saw us bring you breaking news that Unilever is placing a new packaging label directly after the ‘best before’ text on certain food products: ‘often good after’.

The initiative, developed in collaboration with Too Good To Go and industry players, aims to reduce food waste at the consumer level. And, with food waste firmly in the spotlight over the past 12 months, it certainly caught the attention of our readers as the most shared story in 2019 across social media platforms Facebook and Twitter.

“53% of Europeans don’t know the difference between ‘best before’ and ‘use by’ when it comes to food labelling,” Too Good To Go CEO Mette Lykke told FoodNavigator. “Therefore, we decided to team up with a number of food manufacturers to rethink the scheme. ‘Best before’ is a guideline that has to do with the quality of the food. It is still safe to eat when the date expires, and it is up to the consumer to use their senses and common sense. We wanted to clarify that by adding ‘often good after’ to the date labelling.”

Finnish start-up Solar Foods has developed a complete protein made from carbon dioxide, air and electricity, CEO Pasi Vainikka told FoodNavigator.

Branded ‘Solein’, the ingredient aims to boost sustainable protein content in products such as bread, pasta, yoghurt, and ready meals.

When brands like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods scale-up further, Solar Foods’ CEO and co-founder Pasi Vainikka suggested Solein could help meet their high protein demands. “They need a lot of protein ingredients…[and] we can provide a way for them to disconnect from agriculture,” he told FoodNavigator.

In the future, Solar Foods could also help feed cultured meat cells the ‘amino acid cocktail’ required to produce lab-grown meat, Vainikka continued.

The company hopes to be part of a shift to reduce our dependence on conventional farming systems.

2019 saw food additive E171, titanium dioxide, come under sustained pressure from European civil society groups who raised concerns over the safety of the ingredient.

Camille Perrin, food policy lead at European consumer organisation BEUC, told us it was time the EU applied the precautionary principle and remove E171 from the list of permitted food additives. "Prevention is better than cure," she argued.

With food safety so high up the agenda and widespread mistrust of chemical sounding ingredients propelling the clean label trend, its easy to see why this was such a widely shared article in 2019.

Sticking with the theme of food safety, another topic that got FoodNavigator readers tweeting was the accusation that the EFSA's decision making was biased by conflicts of interest in relation to its approval of controversial sweetener aspartame.

According to UK academics at the University of Sussex, the safety of aspartame for human consumption has not been ‘adequately proven’.

Since 1974, research has linked aspartame consumption with heightened risk of brain damage, liver and lung cancer, brain lesions and neuroendocrine disorders, the Sussex researchers stressed.

Nevertheless, in 2013 the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that aspartame and its breakdown products are ‘safe for [the] general population’, including infants, children and pregnant women. At the time, EFSA ruled out potential association between aspartame consumption and brain damage or cancer.

Currently, in Europe aspartame is authorised to be used as a food additive in foodstuffs such as drinks, desserts, sweets, dairy, chewing gums, energy-reducing and weight control products and as a table-top sweetener.

Professor Erik Millstone, one of the report’s authors, told this publication the research provides ‘robust grounds’ for consumers to mistrust EFSA and its judgements.

“EFSA was supposed to provide ‘evidence-based policy-making’, but instead it seems to be reproducing the old way of providing ‘policy-based evidence selection and interpretation’.”

Linking the hot topics of diet, health and protein consumption, this story questioned the link between meat eating as part of a healthy diet and the development of Western diseases.

Research published in Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition contended there are a wide range of benefits delivered by meat that are not always easily obtained from plant materials.

A large reduction in meat consumption, such as has been advocated by the EAT-Lancet Commission, could therefore ‘produce serious harm’, according to academics.

“Although meat has been a central component of the diet of our lineage for millions of years, some nutrition authorities—who often have close connections to animal rights activists or other forms of ideological vegetarianism, are promoting the view that meat causes a host of health problems and has no redeeming value,” wrote Frédéric Leroy and Nathan Cofnas.

“Meat has long been, and continues to be, a primary source of high-quality nutrition. The theory that it can be replaced with legumes and supplements is mere speculation.”

2019 was certainly a year when food tech developments caught the imagination of FoodNavigator readers.

Vertical farming has been hailed as one solution to the challenges presented by a rising population and increased urbanisation. As our analysis of the emerging technology demonstrated, vertical farming offers a number of benefits. Shorter supply chains are able to deliver fresher products to urban populations and technological advances continue to make vertical farming more effective and efficient.

Vertical farming can produce more food from fewer land and water resources. Vertical farming methods also negate the need for harmful chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

There is, however, a catch.

Growing produce stacked on shelves indoors requires significantly more energy use than conventional agriculture. Vertical farms rely on artificial lighting even if there are windows due to the narrow and deep shelves used to increase the yield per square foot. And while climate control systems provide optimal growing conditions, they are also energy hungry.

To address both the affordability and emissions impact of large-scale vertical farming, a clean energy revolution is necessary.

In the future, technological development is likely to focus on improving affordability and addressing concerns over energy use.

The food industry must deliver healthier food in a more sustainable way and utilise new technologies that meet changing consumer expectations. Nestlé plans to be at the forefront of this shift, EVP and CEO of zone EMEA Marco Settembri told us last February.

Settembri called out a number of focus areas for the company, from delivering healthier products through reformulation efforts, to reducing the impact of its supply chain on the health of the planet.

Looking to the future, Settembri said he believes personalised nutrition will be an important long-term trend.

To deliver true personalisation, the industry needs to move beyond segmentation.

“We are already working with new tech. We are working on personalisation already,” Settembri said. “Tech will help us enormously in the future to give you exactly what you want. How you want. With the taste that you want and the shape that you want.

“3D printing can help a lot in that sense. We are investing a lot in [examining] what would be the 3D printing effect on our different categories. We do believe that personalisation is the future.”

The impact of animal agriculture on biodiversity and climate was a hot topic that continued to gain steam as 2019 came to a close.

The debate spilled into the mainstream after a BBC documentary sought to highlight the negative consequences of meat production.

In the documentary, animal biologist Liz Bonnin investigates the environmental impact of animals being raised to supply the world's demand for meat, and looks at efforts designed to reduce the effects.

She noted: “In the last 50 years the global cattle population has increased by 400 million, the number of pigs has doubled and the number of chickens has increased five-fold, and all to keep up with our meat-eating demands.

“This is having a devastating effect on our ecosystems as more and more land is being used for meat production, intensive farming is polluting our rivers with animal waste and the ever increasing number of livestock is contributing to global warming.”

But Patrick Holden, CEO of the Sustainable Food Trust (SFT), told us there needed to be a differentiation ‘between the livestock systems and meats that are part of the problem, and those that are part of the solution’.

"There is no doubt that grain fed, intensively farmed livestock, including those found in feed-lots in the USA, are hugely damaging to the environment and public health, and for this reason should be phased out entirely,” he said.

However, he added that sustainable agriculture represented one of the most ‘significant opportunities to mitigate irreversible climate change, primarily through the regeneration of our soils’. Grazing ruminant animals (including cattle and sheep), have a critically important role to play in rebuilding our soil fertility and carbon stocks, he said.

“We must move away from the prominent models of intensive, often monoculture systems which rely heavily on chemical inputs, towards more regenerative, mixed farming models, that integrate the production of plants for human consumption with natural soil fertility building phases within rotations.

“This can include the introduction of cover cropping and grass, which when grazed in a sustainable way can not only produce food we can eat, in the form of grass fed meat and dairy, but also improve the fertility of our soils.”

The heated debate certainly got FoodNavigator’s readers talking – and reaching for the share button.

Given the booming interest in plant-based ingredients, it should come as little surprise that this was one of FoodNavigator's most shared stories for 2019.

The six ‘most promising’ plant-based proteins for the food industry have been identified by researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, and Givaudan.

The scientists scored the protein sources according to commercial, nutritional and sustainability factors.

Leading the list of potentially ‘game changing’ proteins is the staple grain, oat.

Oats are versatile and resource-efficient, noted Givaudan, with key nutrition benefits. The grain contains 16g of protein per 100g, and serves as an “excellent” source of vitamins, minerals, fibre, antioxidants, and essential amino acids.

Three members of the legume family were selected by Berkeley researchers: mung beans, garbanzo beans (or chickpeas) and lentils.

Flaxseed, or linseed, could prove ‘game changing’ in the protein sector, in part, due to its agricultural production. While currently limited to certain regions – including Russia and Belgium – its production is more efficient than pea protein, and “easily scalable”, according to Givaudan.

Coming in at number six, sunflower seeds are effective, versatile, and resource-efficient, claims Givaudan.