Sustainability is the driver for the protein transition, which continues to gain traction globally. But to succeed in the long term, it must be supported by economic benefits for the manufacturer. In the face of external factors such as the volatile energy market and legislative efforts to reduce greenhouse gases, manufacturers may seek to improve the value of alternative proteins by reducing the cost of producing them. But Kevin van Koerten, Project Manager Processing at NIZO, explains that there is another approach: empowering sustainability in the food transition through innovative processing and sequential extraction and purification, to deliver higher value alternative proteins.

How do you increase the value of a plant protein?

Any conversation around protein value must start with functionality, because food product development is built around functional ingredients. This could include structured materials delivering ‘bite’, binders that keep products together, or emulsifiers that keep beverages mixed. While there is some innovation in mildly extracting less-refined proteins with more general fractions that can deliver, for example, combined functionalities, this approach would require a radical change in how products are developed. Therefore, with the current product development approach, when you wish to replace an animal-origin ingredient with an alternative, you need to extract a protein ingredient with the functions you desire.

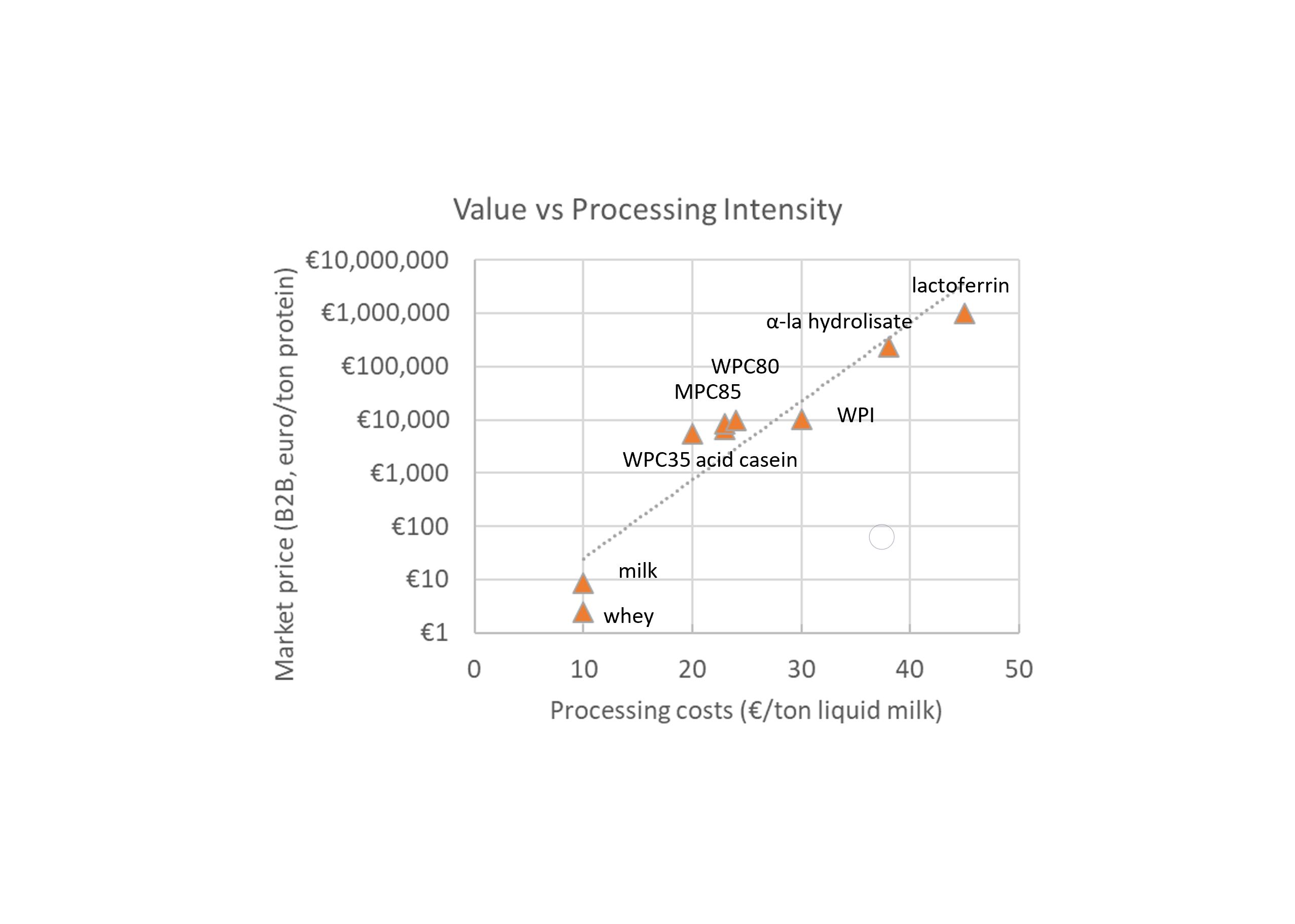

Both value and cost rise with protein functionality. However, the dairy industry shows us that this is not a linear relationship: more functional proteins cost more to extract, but their market value then increases exponentially. Furthermore, it is possible to optimise the full value of a protein source through sequential purification of proteins.

What is sequential purification of proteins?

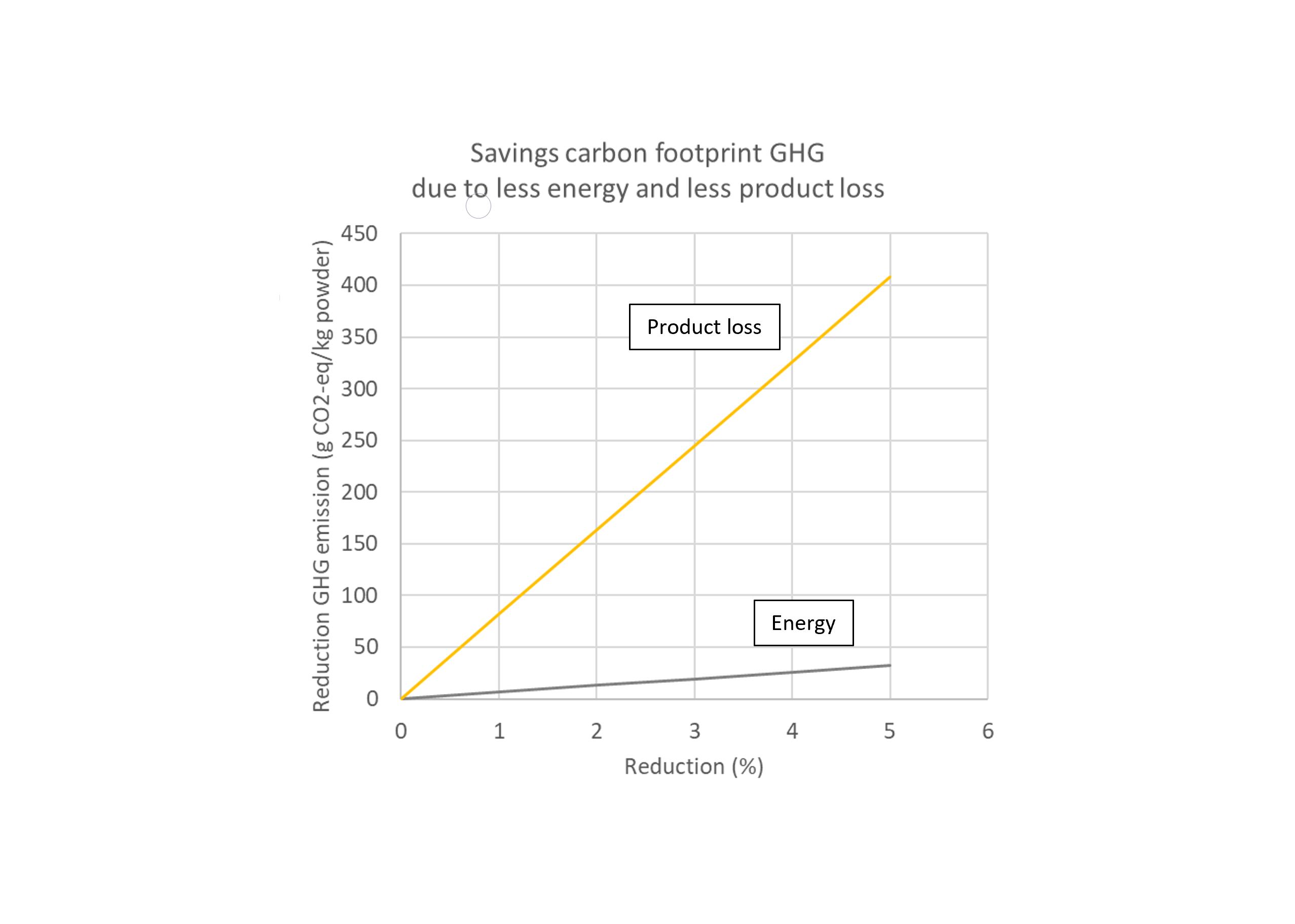

Sequential purification involves extracting multiple types of proteins from the protein source, using different extraction techniques. The dairy industry has perfected this approach over the past 50-70 years. It allows you to maximise the value extracted from the protein source, and use more of the source material, which reduces waste and product loss. Reducing product waste has been shown to lead to higher reductions in greenhouse gases and energy costs than efforts to cut energy usage.

Is it possible to achieve the same results with plant proteins?

Plant protein manufacturers are already taking the first steps, extracting multiple proteins with different functionalities from a single source. So whereas you used to have a single ‘potato protein’ or ‘pea protein’, now you may have an acid-soluble protein fraction and a neutral-soluble protein fraction. However, there is a lot of exploratory work to be done, to identify all the different proteins that can be extracted, and then to optimise the process design to get the most value. It’s a complex challenge.

What are the challenges of optimising processing design for plant proteins?

Firstly, all milk is essentially the same, and responds to processing in the same way. But every alternative protein source and composition is different, and presents its own challenges. On the other hand, there are some common challenges most plant proteins share, such as higher viscosity, which negatively impacts processing efficiency through, for example, increased blockage of equipment.

Another challenge is that during protein extraction and processing, plant proteins can lose functionality, flavour and solubility. Innovative mild processing techniques can provide a solution to this, offering an alternative to acid precipitation, which may be cheaper and easier to use, but which increases product loss and reduces functionality.

What mild techniques can be used? One important development has been in the use of polymer or ceramic membranes to filter the material stream. It’s been proven in the dairy industry, and is now moving into plant protein extraction. Membrane filtration delivers higher yields and better functionality than acid precipitation, and is more ecologically friendly. By combining different membrane and processing conditions at different stages, you can extract different proteins with different functionalities.

Are there hurdles to using membranes?

Plant proteins can lead to increased fouling of membranes, due to a variety of mechanisms: the high viscosity already mentioned, for example. Techniques such as ultrasound or nano bubbles, or adapting the pretreatment, may be able to solve this issue. Furthermore, there is a lot of research and development taking place on the membranes themselves, for example adapting the polarity, which may reduce the ability of polyphenolics to attach and block the membrane pores. We need this type of innovation to optimise the potential of the plant proteins.

How can manufacturers deliver that innovation?

Luckily, we don’t have to start completely ‘from scratch’: both manufacturers and food research companies like NIZO have collected a lot of data that can be helpful. At NIZO, for example, we have a very broad range of data that can be used to help select the best starting point, or the optimal next step, including exploring which plant proteins might be able to deliver the required functionality.

Manufacturers, on the other hand, have masses of in-depth data on their specific processes and products. And with sensors now so readily available, they can collect even more, at every stage of processing. This data could provide insight into specific opportunities for optimisation. Techniques such as modelling and artificial intelligence (AI) are key to exploiting such data, to enable both a faster design trajectory and a higher success rate for process optimisations.

How can techniques such as modelling and AI give manufacturers a ‘helping hand’?

Modelling, for example, can help ‘fill in the blanks’ of missing data: think of using high-throughput screening to define optimal hydrolysis conditions. AI can then look at the entire data landscape and find patterns humans might not see. However, AI results are far from perfect; you still need knowledgeable humans to sift through the results, to filter out the unrealistic AI-generated suggestions and outcomes.

With all the challenges, is it worth it for manufactures to look beyond the ‘low-hanging fruit’?

The industry has only touched the surface of what we can do with plant proteins. Can they be sustainable? Yes. But they can also make good business and financial sense for manufacturers, especially if you can extract all the potential value. You need an understanding of both processing techniques and protein sources. And you need to take a holistic approach, which looks at the process from start to finish. It’s a major challenge for the industry, and we are just at the beginning of the journey, but we believe the payoff will be more than worth the effort and investments.