Alcohol production is considered a carbon-intensive process. Not only does it rely on the cultivation of raw materials such as grains, beets and potatoes, but the fermentation process releases a considerable amount of almost pure CO2.

What if alcohol production could be disconnected from agriculture, and the CO2 emitted repurposed to produce a new kind of alcohol ‘made from air’? This is the idea behind start-up Aircohol’s closed carbon loop technology, which it says can reduce the carbon footprint of drinks by 50%.

Zero CO2 released into atmosphere

Capturing carbon dioxide from alcohol fermentation is a not a new idea. Some distilleries and breweries have implemented carbon capture devices, so they can reuse that CO2 in their own production processes, whether to stabilise the carbonation in beer, to carbonate non-alcohol beverages, or to remove oxygen from bottles and cans during the packaging process.

But this practice remains relatively uncommon. Further, breweries and distilleries that do install capturing devices, don’t often capture 100% of the CO2 emitted during fermentation because there is currently no use for it, or business case for doing so.

This puts alcohol businesses in a tricky situation, according to founder Simo Hämäläinen. “They have an almost pure CO2 source that partly or entirely goes into the atmosphere, but at the same time they want to be more sustainable.” Indeed, the alcohol industry is striving towards more sustainable operations. Spirits major Diageo and beer giant AB InBev, for example, have committed to net zero emissions across their direct operations by 2030 and 2040 respectively.

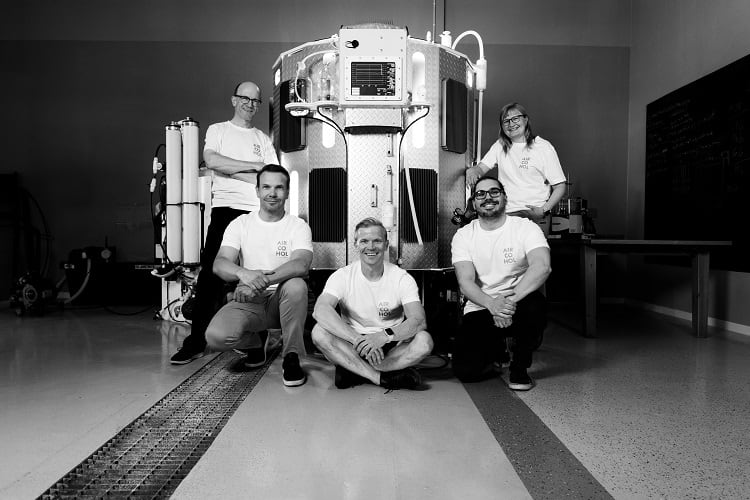

Finland-based Aircohol has developed technology that enables captured carbon to be used as a raw material in the production of a new type of alcohol by breweries and distilleries. “We take that CO2 and feed it into Aircohol process,” Hämäläinen explained. “We have developed a unique bioreactor and a plant-based bioprocess that provides optimal growth conditions to grow and produce biomass.”

While Aircohol’s patent is pending, the company remains tight-lipped about which plant-based input is helping encourage biomass production.

The biomass then goes back into the brewery or distillery’s alcohol fermentation process, to produce more drinks. The start-up says its technology can be ‘seamlessly’ integrated into existing brewery or distillery production processes, creating a sustainable carbon loop and ensuring zero CO2 is released into the atmosphere.

Since Aircohol itself is not a carbon capture nor a drinks company, it sees itself as playing a central role in connecting these two operations. “We are the circular economy piece of the process,” the founder told this publication. “We don’t capture the carbon and we don’t manufacture the drinks – that’s the job of the distillery or brewery.”

A new alcohol completely disconnected from agriculture

Unlike conventional alcohol production, the only external ingredient required to produce alcohol with Aircohol technology is CO2. “We don’t need anything from the field. We don’t need barley [as is used in whisky or beer] or potatoes [for vodka]. We cut the entire carbon footprint from the growing and sourcing of raw materials, which can be significant in many cases,” the founder

explained.

Indeed, once Aircohol’s technology is up and running, the resulting alcohol produced is almost completely disconnected from agriculture – with the exception of the undisclosed plant-based ingredient. Instead of the usual year-long wait for traditional alcohol-producing crops to mature, Aircohol’s ‘harvest season’ lasts a mere couple of days.

Breweries and distilleries can use the new alcohol how they please, whether that’s on its own as a spirit, or mixed in with existing ingredients for a carbon-reduced beer or juniper-infused gin. The start-up is excited about the possibilities, given that its technology will produce a ‘new flavour profile’ for companies to play with.

“Businesses can manage how much of that flavour they want to maintain. It could be distilled to ABV 96% as a vodka and then blended back to ABV 40%, when there would be very little taste from Aircohol’s ingredient,” Hämäläinen explained. If distilled to ABV 60% however, consumers would be able to taste the ingredient, offering ‘new flavours and new opportunities’, he said.

In beer production, the brewer would replace part of its barley or wheat content with Aircohol’s ingredient to reduce CO2 emissions and add its unique flavour profile.

Indeed, Aircohol has already entered a strategic collaboration with alcohol company Brukett in Finland. Plans are underway to upscale the technology to industrial size and initiate production of the ‘world’s most sustainable beverages’ in 2024.

“Collaborating with Aircohol aligns directly with our strategy: we want to take innovative and even radical steps to reduce the environmental impacts of our operations,” commented Brukett CEO Mikko Ali-Melkkilä on the collaboration. “It’s significant for our business that we can produce tasty drinks with minimal environmental impact, accompanied by an engaging story.”

Developing ‘greener’ booze to comply with EU law

Research suggests consumers want to buy sustainable food and drink. A recent survey conducted by IPSOS found that 58% of Europeans consider the climate impact important when buying food and beverages, while 31% of Europeans said they already make sustainable choices when it comes to their buying habits.

This is reflected in NPD across the alcohol industry. Earlier this year, for example, London-based brewery Gipsy Hill claimed a ‘world first’ in creating carbon negative beers without the use of offsets. The concept is based on regenerative farming.

But R&D is also playing a role in the development of ‘greener’ booze offerings. Over in the US, Air Company is using renewable energy to convert carbon from the air into alcohol. Made from just carbon dioxide and water, it’s another way of producing ‘alcohol from air’.

For EU-based Aircohol, this strategy is off the table. “At the beginning we looked at different ways to produce alcohol from CO2. According to EU law alcohol must be produced from agricultural source, so every technology is not suitable or would require a long Novel food approval process,” explained Hämäläinen.

Another company producing food ‘from air’ is Finland-headquartered Solar Foods. Aircohol also investigated its approach, which is based on a bioprocess whereby microbes are fed with gases (carbon dioxide, hydrogen and oxygen) and small amounts of nutrients. But since Solar Foods is developing a novel microbial protein that must undergo Novel Foods approval before being marketed in the EU, the Aircohol founders again looked elsewhere.

The result is a process that uses ingredients already known to the Novel Foods register, and thanks to its plant-based input, aligns with the EU’s agricultural requirement for alcohol.

Aircohol recently secured €2.4m in funding and through its collaboration with Brukett is already testing vodka and beer, as well as non-alcohol beverages, for the market. “Our next step is to scale the technology to industrial size and together with Brukett, begin producing drinks to the consumer markets.”