The Nutri-Score debate continues to rage. On the one side, proponents of the front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition label argue Nutri-Score helps consumers make better informed and healthier choices while encouraging manufacturers to improve the nutritional composition of their products.

On the other, opponents accuse Nutri-Score of discriminating against traditional foods and being opposed to the Mediterranean diet, which a new report – co-signed by more than 300 scientists and health professionals in Europe – describes as ‘fake news’.

In making the case for why the European Commission should choose the Nutri-Score nutrition label for its harmonised mandatory nutrition label, the EU Scientists & Health Professionals for Nutri-Score report has addressed questions that may be ‘legitimately’ raised, but which it claims are ‘often misused and exploited as fake news by lobbying groups’.

So what are the most frequently asked questions? And how does the report rebut common ‘misunderstandings’?

Why doesn’t Nutri-Score take ultra-processing into account?

Ultra-processing in food and drink is attracting increased attention, as research linking ultra-processed food (UPF) with a greater risk of developing cancer and a higher mortality rate come to light.

Research also suggests that consumers are unclear about which foods are ultra-processed, and which are not. Despite this confusion, a recent survey suggests that consumers want to avoid UPFs.

A common question concerning Nutri-Score, therefore, is why the algorithm does not take ultra-processing into account.

Nutrition labelling scheme Nutri-Score was developed in France in 2017. Its algorithm ranks food from -15 for the ‘healthiest’ products to +40 for those that are ‘less healthy’. Based on this score, the project receives a letter with a corresponding code: from dark green (A) to dark orange (E).

The fact is that no FOP nutritional label in the world includes other health dimensions of food, such as the presence of additives, pesticide residues, or ultra-processing, according to the report authors. Instead, ‘as with all other FOP nutritional labels’, Nutri-Score only provides information on the composition/nutritional quality of food.

It would be scientifically impossible to encompass ultra-processing into a single FOP label, note the authors, who say that helping consumers to recognise ultra-processed foods is important.

One possibility could be to add extra information – such as an ‘ultra-processed’ marking – to the current Nutri-Score label. A prototype has been tested in a randomised controlled trial to evaluate how such a logo might improve consumers’ abilities to identify ultra-processed foods. Results suggest participants were able to identify which foods were ultra-processed.

Developed in 2009, the NOVA system splits levels of food processing into four classifications, from raw and minimally processed foods (NOVA 1); to processed culinary ingredients (NOVA 2); processed foods (NOVA 3); and ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4).

The NOVA system has received criticism for failing to distinguish between food formation and food processing, and not distinguishing between different NOVA 4 products, such as soft drink and pre-packaged bread.

The report stresses, however, that some ultra-processed foods may have a fairly good nutritional quality, and could be classified Nutri-Score A or B. On the other hand, some of the foods considered not to be ultra-processed (according to the NOVA food classification system) can also present a low nutritional quality.

“For example, pure grape juices are NOVA 1 but they contain more than 16g of sugar/100ml, justifying their classification as Nutri-Score E,” note the report authors.

Moreover, unlike Nutri-Score, the NOVA classification does not discriminate between the nutritional composition of products. According to NOVA, for example, there is no differentiation between vegetable and animal fats.

‘Nutri-Score attacks traditional and Mediterranean foods’

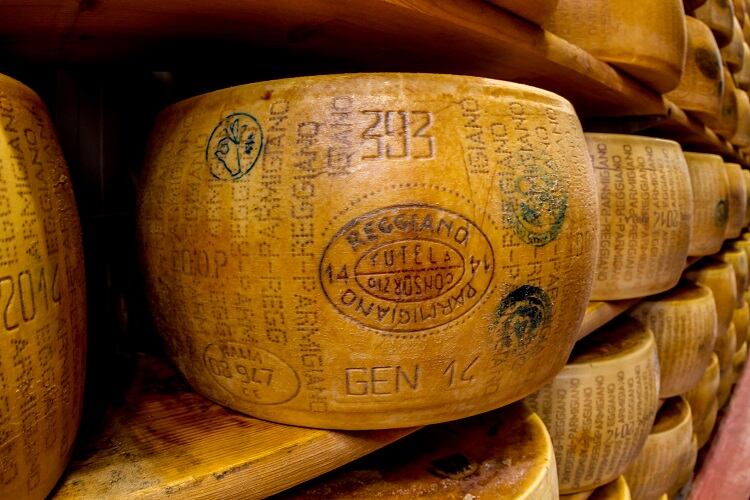

Nutri-Score has long been accused of penalising traditional foods, including single-ingredient products protected by geographical indications such as Kalamata olives from Greece, Parmigiano Reggiano from Italy, or Camembert from France.

But the report rebuts this allegation, arguing that most traditional foods with a designation of origin have a ‘rather favourable’ composition and achieve a Nutri-Score A or B.

If cheese or processed meats – whether associated with a geographical indication or not – are ranked Nutri-Score D or E, this relates to their ‘high’ content of saturated fatty acids and salt, as well as their high calorie density, they note.

“This does not mean that they should not be consumed. But being classified as Nutri-Score D or E simply reminds consumers that these products should be consumed in moderate quantities and with a limited frequency, or should lead to rebalancing the rest of the meal or the food intake of the day/week.”

Just as proponents of Nutri-Score argue the FOP label does not discriminate against traditional foods, they also contend the algorithm is not opposed to the Mediterranean diet.

‘On the contrary’, note the report authors. “It is totally in line with the traditional model of the Mediterranean diet,” which champions consumption of fruits, vegetables, pulses, whole grains, a moderate consumption of fish, limited consumption of dairy, and low consumption of meat.

The Mediterranean diet is also characterised by its favouring of olive oil among the added fats. Previously, olive oil was ranked Nutri-Score C, but an algorithm update has seen it move up the scale to B – the best possible grade for added vegetable fats and oils.

Following a Nutri-Score algorithm update late last year concerning food products, France recently announced another concerning beverages. This latest update predominantly impacts Nutri-Score classification of milk-based beverages with high levels of sugars, low-sugar beverages, and beverages with non-nutritive sweeteners.

‘Nutri-Score is at odds with public health recommendations’

Last month, the Netherlands announced Nutri-Score would ‘definitely’ be adopted as its official voluntary nutrition labelling scheme. The announcement was deemed controversial, with members of the Netherlands’ nutritional science community arguing the FOP labelling scheme contradicts the country’s food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG).

In the EU Scientists & Health Professionals for Nutri-Score report, published today, the authors stress Nutri-Score is not a substitute for such public health recommendations, but should be complementary.

“While nutrition labels apply to specific products, nutrition recommendations focus on the consumption of large ‘generic’ food groups like fruits and vegetables, legumes, dairy products, meat, fish, added fats and sweet products,” note the authors.

But within generic food groups, there is a ‘large’ variability in composition across the range of industrial foods available to consumers.

Under the definition of ‘fish’, for example, one may consume raw, canned, smoked, patty, breaded or minced fish, explained Serge Hercberg, professor of nutrition at the Université of Sorbonne Paris Nord’s Faculty of Medicine, whose work formed the basis of Santé Publique France’s Nutri-Score.

“The Nutri-Score provides additional information: fresh salmon ranks A, canned salmon ranks B, and smoked salmon D…

“Therefore, the Nutri-Score is truly complementary to the GBDGs [such as the Netherlands’ Wheel of Five] because it can help consumers adjust the quantity and frequency of consumption of [for example] different types of salmon product in an easy way.”