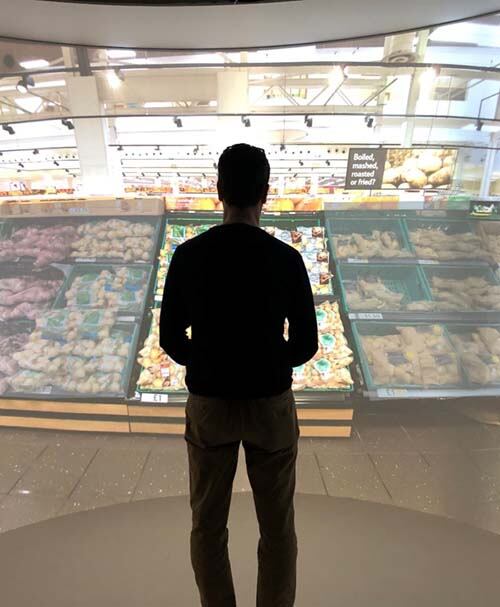

The Perceptual Experience Lab (PEL) at Cardiff Metropolitan University is a collaboration between the university’s School of Art and Design and the co-located ZERO2FIVE Food Industry Innovation Centre, which provides food and drink businesses with technical, operational and commercial support. The immersive, multi-sensory digital theatre is an impressive sight. The synthetic reality laboratory combines a high-resolution screen that wraps 200° around the research participant with immersive sound, smell, air movement, physical objects and temperature to create simulations of environments in a laboratory setting where close monitoring, control, repetition, recording and analysis is possible.

“The PEL is used to stage simulated task environments (STE) for user-testing praxis, food safety training and consumer behaviour research,” Dr Joe Baldwin told us during a visit to the site. The PEL’s ‘innovative technology’ creates a ‘unique research environment’ that can be used to generate ‘real life-scenarios’, the scientist continued. “For example, consumer behaviour in a supermarket can be reproduced in a laboratory situation enabling different purchasing scenarios to be created and controlled,” he explained.

Academics in the PEL team have also developed unique integrated eye tracking technologies, which allow gaze analysis. This, they say, provides insight into the respondents’ ‘actual behaviour’ and validation of questionnaire responses.

This insight is invaluable for the fast-moving packaged foods space where snap decisions are commonly made in the supermarket aisle, Dr Baldwin suggested. “Packaged food products are increasing rapidly in choice, and competition is ever more intense. More than 70% of consumers make decisions on daily necessities in store, 85% of goods are purchased without picking up an alternative option, and 90% are purchased after examining only the front packaging of a product without having it in their hands. Therefore, it is paramount for companies to ensure that their products are eye catching,” he told FoodNavigator.

Simulated environments for consumer insight

“One of the main drivers behind the development of the PEL was to provide a controllable user testing research space where theoretical knowledge of behaviour, marketing and design, could be combined with the practical implications of user testing,” Dr Baldwin explained. “The PEL has contributed to the successful delivery of commercial and academic projects,” he said pointing to a collaboration with Puffin Produce - the largest supplier of Welsh produce in Wales – as an example of using low-cost simulated environments to assess and gather in context packaging design.

Puffin Produce approached ZERO2FIVE for support with market research through the Welsh Government and EU-funded Project HELIX. The company had a new packaging design that they wanted to test against their existing packaging and a retailer’s own label.

The PEL team designed an appropriate experimental protocol, created visual stimuli to place into a virtual supermarket fresh produce aisle and recruited participants from Puffin’s target consumer demographic. These would-be shoppers stood in the virtual supermarket wearing eye-tracking glasses. They were asked questions to determine what pack designs were most ‘attention-grabbing’, 'fresh', 'Welsh' or 'premium'. They were also asked what packages they preferred and which they were most likely to buy. At the same time, the eye-tracking glasses recorded where people were looking and for how long. Follow-up questions were asked around the rational for the decisions they’d made.

“Participants wore eye-tracking glasses to track their consumer attention throughout their shopping experience and verbal responses were given to questions from the marketing team. Importantly, the use of the hybrid photographic media methodology in the PEL revealed key insights into consumer decision-making in response to alternative packaging designs,” Dr Baldwin recalled. “Robust design feedback was provided for the company and was used to inform further packaging development. In a successive study, these design insights were used to inform graphic elements of a second packaging design iteration. Interestingly, the second packaging design iteration performed better than both previous versions. Key graphic elements included from the previous study resulted in a preferred packing design and validated that the PEL could play a valuable role in the packaging design process. A further study was proposed, and the company provided a new packaging concept which they wanted to test against their existing packaging and a retailer’s own label in the fresh produce supermarket aisle. Participants were asked questions concerning their views on the graphical elements of the packaging design whilst wearing eye-tracking glasses in the PEL space.”

This research offered validation for the final packaging design. The target 35-50-year-old female consumer preferred the new Blas-y-Tir packaging design over the existing and own label designs and that the new design had the potential to win over new customers that didn’t purchase the brand. The overall consensus was that the new packaging design was more tasteful and modern, had better imagery and a simpler layout, it was found.

"Using the Perceptual Experience Laboratory allowed us to test our new packaging designs with consumers in a close to real life environment which otherwise wouldn’t have been possible. The valuable feedback provided evidence for us to take to retailers about the shelf standout of our new packaging,” reflected Puffin Produce MD Huw Thomas.

The benefits of simulated reality

Why go to all this trouble? Wouldn’t it be simpler to carry out this kind of test in a supermarket?

Probably not, Dr Baldwin noted. For one thing, supermarkets aren’t necessarily thrilled to welcome behavioural research teams into their aisles. But the PEL has advantages, we heard.

By re-creating settings like supermarkets, the PEL allows researchers to observe participants who behave more closely to real life situations than they would in other options like desk-based questionnaires or focus groups. In the context of the food industry, it is important that study participants feel connected to a shopping context, otherwise they may ‘remove themselves from a shopping mind-set’ and ‘assume a more aesthetically critical mentality’. This turns the process into a beauty contest that doesn’t actually reflect how purchase decisions are made. “A simulated environment can replicate external variables (to some extent) to simulate a real-life context in a laboratory setting. The simulated environment is also customisable, it ensures confidentiality, and enables the easy set-up of an array of data recording devices.”

Unlike being in an actual supermarket, the laboratory ensures consistency in the research methods. “Extraneous variables can be easier to control within an STE compared to a real (field) environment, which can be too complex, thus increasing the researcher's ability to study behaviour and the validity of study data. In contrast to field research, when carrying out ‘in-vitro’ laboratory studies it is almost impossible to provide an equal level of realism. Crucially, ‘in-sitro’ STE scenarios that match as close as possible to the field environment are advantageous because they allow researchers to maintain a high level of experimental control,” we were told. “The PEL provides an unhindered space to operate wearable eye-tracking technology, allowing an unbiased visual account of user engagement and product preference. Fixation data within the context of the field environment removes search task uncertainty and provides robust visual attention insights. Further behavioural analysis is possible through observation lab systems that allow discrete surveillance of participants.”

The benefits of simulated task environments have already been recognised by large multinationals, who will often have in-house capabilities. The facilities at Cardiff Met mean this approach can become more accessible to smaller food makers, Dr Baldwin noted.

“Simulated task environments and eye-tracking technologies are increasingly being adopted by global companies to better understand consumer purchasing behaviour. However, given the technical setup and running costs of STEs, this technology and, at times, eye-tracking is used exclusively for in-house testing by companies with large research, development, and marketing budgets. Dissemination of consumer insights and preference knowledge is restricted. However, the FIC provides commercial access to the PEL and a diverse range of behavioural analysis technologies: wearable and screen-based eye-tracking for attention analysis, an observation system for participant behaviour analysis, facial expression software for the assessment of emotions and heart rate and galvanic skin response devices to measure physiological changes during tasks. As a result, valuable research and insights can be made by small and medium-sized businesses. Making this technology accessible to the to the public domain alongside well practiced technical delivery and academic knowledge within applied user testing is a way in which less affluent companies can level up (dip in and out) without large research budgets.”

Set-up costs aside, using the PEL can offer a cheaper, faster and more effective way to research consumer behaviour, Dr Baldwin continued. “The use of simulated task environments and wearable eye-tracking has created a system in which tests can cheaply, quickly and effectively assess packaging design. The results from packaging experiments cannot definitively improve a packaging design, but rather give guidelines and provide empirical data highlighting perceptions of targeted aspects of design elements. Our method can reveal and confirm general perceptions, and which packaging participants are attracted to, based on design. Equipped with this data, companies or design agencies can use this knowledge to inform future designs. Commercial studies have revealed interesting associations between packaging design elements and their link to the perception of the product. A follow-up step or next step in the design process would be to develop a new packaging design based on insights gained from an initial consumer experiment and to test it against its predecessors to see if there are any significant differences in scores or perception.”

Additional applications: From food safety to training programmes

Packaging design and product placement optimisation are two important areas for STE application. But Dr Baldwin sees other uses for the technology. “To date, we have been using the PEL and wearable eye-tracking technology for doctorial, academic, and commercial research across a variety of sectors; providing Human-Centred user testing, product development, food safety and security training, medical and sports research.”

The scope of this research ranges from the simulation of tourism environments for ‘hedonic wellbeing’, to sports coaching. The PEL has even been used in the production of a ‘wound assessment training video’ for the Welsh Wound Innovation Centre, which is set to be rolled out within NHS Wales next year.

Within the food industry context, the PEL researchers see scope to leverage simulated task environments in training efforts. Work is already underway in the field of food safety.

For instance, Cardiff Met’s Dr Ellen Evans added, her recently completed PEL bakery pilot study focused on promoting food safety hazard awareness in a commercial bakery setting. “The purpose of the research was to explore the feasibility of using the PEL to deliver food safety training within a manufacturing environment. Primarily to inform the creation of effective food safety behaviour training packages,” she told us.

“We are engaging in follow-up research collaborations and opportunities to provide meaningful training opportunities within food industries. This activity will bring a wide-reaching understanding of industry-based food safety auditor-consistency behaviour and knowledge.”