The latest UK government data shows that more than four million children across the country are living in poverty. As families are forced to stretch budgets and manage high housing and energy costs, food insecurity has become an increasingly problematic issue for many households.

Insufficient access to nutritious food is a key part of defining poverty or food insecurity, with children being some of the worst affected. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation notes that, apart from single adults, children are the most likely group to be living with food insecurity. The Food Foundation estimates that four million children are currently living in homes with inadequate access to food – a number that has increased by 50% since April.

“It is with some deep reflection that I am looking at current circumstances around us in the UK and internationally. Unfortunately, despite the work many of us have been doing in trying to tackle this problem, it is only getting worse,” reflected Professor Corinna Hawkes, Director of the Centre for Food Policy at the University of London. “We need to be engaging to look at the links between financial insecurity, poverty and dietary inequalities.”

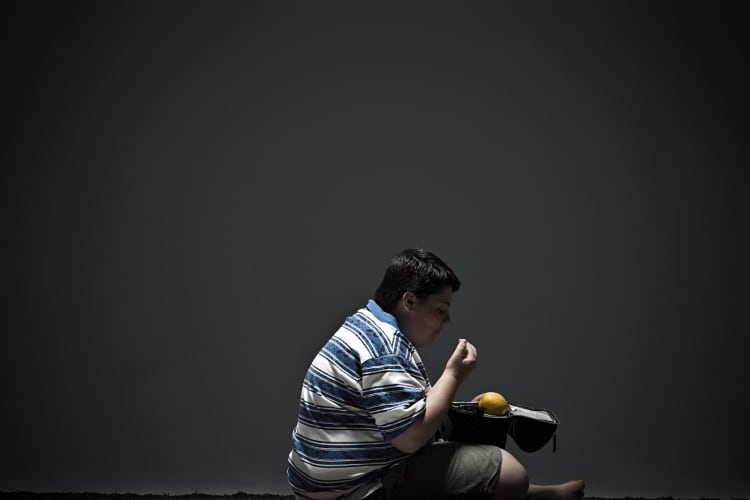

Childhood experiences of food poverty

Professor Hawkes is part of the Lived Experience Research Group at the Centre for Food Policy. Speaking at the BNF event, she noted ‘in this country we mainly fail to reach dietary recommendations’, adding that to understand why we need to look at ‘what’s going on, on the ground’.

A study conducted by Professor Julie Brannen, of the University of London, and Professor Rebecca O’Connell, from the University of Hertfordshire, found that half of parents living in low-income households sheltered their children from food insecurity by limiting their own food intake or skipping meals. Three quarters of parents said they bought or prepared meals that were ‘filling rather than nutritious’, by bulking out meals with cost-effective carbohydrates like pasta or rice. “They bulked out the more affordable foods with carbohydrates, they shopped for value food deals, they limited the amount of fruit they brought and they didn't allow their children to have their friends home,” detailed Professor Brannen.

Nevertheless, one-quarter of children who participated in the study reported feeling hungry due to a lack of food and parents said they struggled to meet appetites of growing children.

In a statement read by Professor Brannen, a boy called Jimmy explained his experience of food insecurity. “Sometimes I go to bed hungry. I just started to grow and when I started to grow, I think my belly started to grow too.”

Support to tackle the issue is inadequate for many families, Professor Brannen observed. “Despite being on low incomes, in terms of eating at school only half of the children in our study were entitled to a free school meal in the UK... Some but not all schools provided children with a meal from their own budget. The children told us the free school meal allowance was not sufficient for their appetites and several mentioned being restricted to smaller items.”

Food poverty feeds unhealthy diets

Poor diet is linked to food insecurity and poverty, speakers revealed. “Adults on lower incomes are more likely to have diets which are higher in sugar, lower in fibre, fruits, vegetables and fish. It is the same for children,” Professor Hawkes stressed. “Children on lower income families are more likely to consume sweetened drinks, more likely to consume very low levels of fruit, and more likely to skip breakfast.”

To develop solutions, it is necessary to recognise the ‘multiple dimensions’ of poverty, food insecurity and unhealthy diets. Describing income as the ‘first element in this relationship’, Professor Hawkes also highlighted the significance of other factors, ranging from the food environment outside the home, to access to cooking facilities within it.

The circumstances that lower income families are confronted with mean they are pushed towards affordable food that won’t spoil and can be stored and prepared easily. Categories that meet these criteria include long shelf life foods, frozen foods and snack foods as well as pre-prepared and takeaway options, Professor Hawkes suggested. These choices, she said, are ‘palatable’ and reduce the risk that food will be wasted but are also ‘often less healthy’.

This pattern also has far-reaching consequences for food preferences. Children of lower income families are not exposed to healthier foods in the same way as their more affluent peers, meaning that they don’t develop taste preferences that favour items like fruits and vegetables, she continued.

Unequal nutrition results in unequal health outcomes

The nutrition that children have access to in their formative years has a lifelong influence on health outcomes, the BNF audience heard. "The whole story of health inequalities is really linked to dietary inequalities,” stressed Dr Ruth Bell, a senior advisor at the UCL Institute of Health Equality. "Tackling inequalities in healthy eating is a key element to tackle health inequalities.”

Recent years have brought ‘major challenges’ to health inequality in the form of austerity, COVID and, now, the cost of living crisis. The impacts can be seen in the increasing disparity between the life expectancy of wealthy and deprived populations in the UK. “In the UK, we are very used to progressive increases in life expectancy... Between 2012-2018 we see that increase in life expectancy slowing down and in effect stalling,” Dr Bell observed. “If you look at the state of health inequalities... we see large differences in life expectancy at birth across areas of deprivation.”

"The impact of poverty is devastating for health. Growing up in poverty is very bad for childhood development [and] educational outcomes. This has knock on effects on employment opportunities. Being in poverty effects the affordability of housing, food, healthy diets and fuel. Being in poverty effects the choices people can make and impacts on the level of control they have.” - Dr Bell

Professor Jason Halford, Head of the School of Psychology at the University of Leeds and President of the European Association for the Study of Obesity, stressed that dietary inequality and associated health impacts also have profound implications for the mental wellbeing of young people.

Detailing the results of the Action Teens study, Professor Halford explained ‘adolescent childhood onset obesity is associated with worse outcomes than adult onset obesity’. These include a ‘substantial mental health burden for children and adolescents’ who are more likely to suffer from depression and low self-esteem. “That relationship is mediated be socio-economic status,” he stressed.

Beyond its health implications, living in food poverty can have a negative impact on social development for children. As Professor Hawkes, the host of the BNF Annual Day noted: “Food is about so much more than nutrition. It is hugely symbolic and plays a major role in people’s lives.”

During the conference, BNF members heard several calls to action, with speakers urging major supermarkets to take responsibility for the role they can play in helping to reduce food inequality. Nikita Sinclair, Portfolio Manager at Impact on Urban Health, said: “If we want our children to be healthy, thrive and grow up to give back to society, we must fix our food system.”

Policy decisions like the expansion of free school meals and interventions like breakfast clubs were a focal point for speakers, with broad agreement that this is an important opportunity to improve the nutritional quality of food that children living with poverty have access to. However, for Professor Brannen, such initiatives may not go far enough. She stressed that food inequalities need to be tackled through a systems-thinking approach that priorities the rights of children.

"Children should have the right to a decent standard of living, with a family income that can provide nutritious food. They should have the right to a nutritious meal at school in the same way that children have the right to education, they should have the right to socialise with friends at home and in their neighbourhoods... these should be healthier places for young people.”