Proponents of food tech like precision fermentation and cellular agriculture believe that their innovation efforts will help feed the growing global population a healthy and sustainable diet. By reducing our reliance on animal agriculture, precision fermentation and cultivated meat developers aim lower the food system’s carbon footprint, cut land-use, and improve water stewardship.

These technologies have attracted a lot of excitement and are securing rising levels of investment. According to CellAgri’s Cellular Agriculture Investment report, it took the sector five years to reach the milestone of US$1bn in funding by 2020. In 2021, the field surpassed US$2bn in funding. Data from Food Strategy Associates shows precision fermentation companies secured around US$750m in disclosed investment in 2021.

But – issues like regulatory approval and consumer acceptance aside – a significant barrier remains. Scaling for impact.

Yvonne Armitage of the Centre for Process Innovation (CPI) believes that scale is something food tech start-ups often don’t think about early enough. “Everybody is focused on getting their product out of the fermenter,” she said speaking at the Future Food Tech conference in London last week.

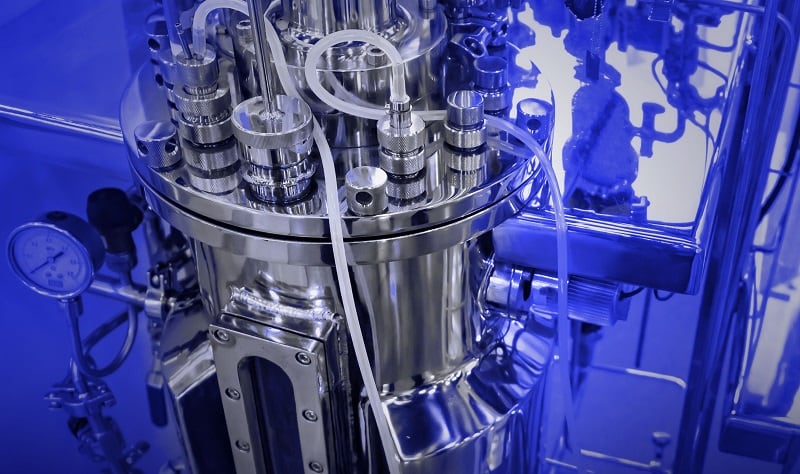

In cellular agriculture, even the ‘pathology of the cell itself’ stands in the way of scaling production processes, David Brandes, Co-Founder and CEO of Planetary, noted. Animal cells are ‘very fragile’, the food tech entrepreneur elaborated, and moving their production out of pilot and to a commercial scale of, say, 200,000 litres will require innovation on the equipment side.

“Fermentation is a more developed tech,” and it is here that we are already seeing the first suggestions that companies are starting to scale operations, Brandes noted.

Investments in production capacity

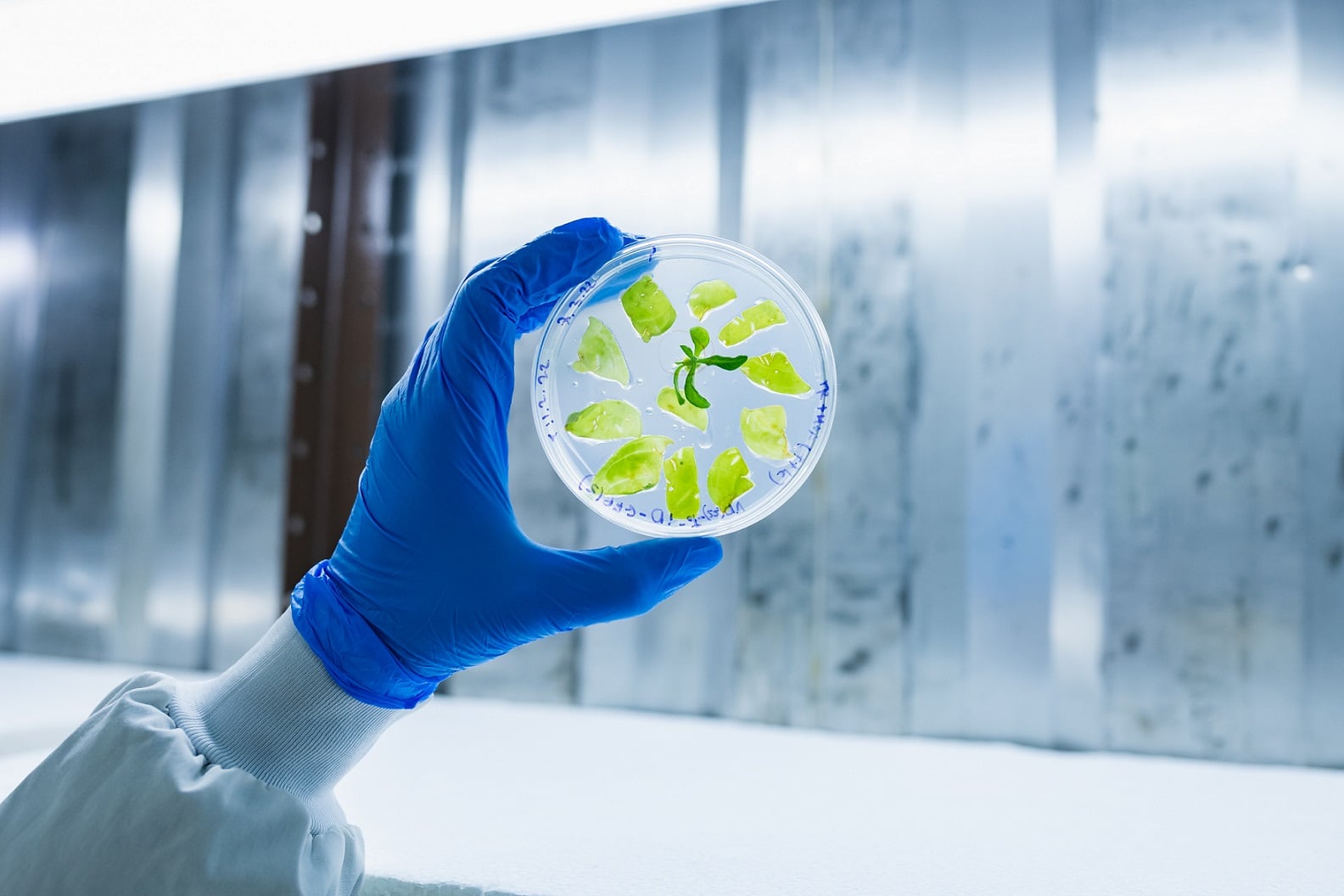

Mushroom fermentation food tech MycoTechnology is one such pioneer. The US-based group makes ingredients using the fibrous root structure of mushrooms, known as mycelium. It operates its own production facility where it leverages submerged fermentation to produce plant protein with mushroom mycelia and natural flavour modulators. The company is also establishing a venture in Oman where it will apply a new ingredient to its proprietary fermentation platform: locally grown dates.

Looking back on the journey to get to this stage, CEO Alan Hahn reflected: “The challenges were, one, raising money… and two, convincing investors to put steel in the ground. They always want a co-man,” the former Silicon Valley executive observed.

This wasn’t the right direction for MycoTechnology, who spent considerable time and resource on failed efforts to work alongside co-manufacturers. “We were paving the way,” Hahn told the food tech audience. “We searched the world… The kind of equipment we needed just didn’t exist.”

While going it alone and developing its own plant might have been a mountain for MychoTechnology to climb, it did bring considerable know-how and has resulted in more than 61 patents, with more still pending.

Nevertheless, collaboration on innovation and production processes and the transition from ideation, to pilot, to production scale does carry some significant advantages, the other speakers agreed. Brandes, who heads up a Swiss company building bioprocessing capacity globally and offering a manufacturing platform that provides industrial scale to fermentation front-runners, stressed that ‘there are a wide range of options’ to now work alongside co-manufacturers.

Jonathan Berger, the CEO of Israeli food tech incubator The Kitchen Hub, sits on the board of portfolio company and cellular agriculture developer Aleph Foods. He revealed Aleph has decided to take one of these different routes to scale. “We are driven by cost reduction so when there is a way to outsource while protecting our company’s IP we do that. There are many tech providers,” he noted.

CPI’s Armitage views outsourcing certain parts of the development and production process as a way to de-risk the proposition and suggests that collaboration can accelerate innovation in the field as a whole. “De-risking is really important,” she stressed. “You can’t go straight to scale.”

Armitage advises working with someone ‘who’s done a lot of different bioprocesses’, including leveraging cross-industry learnings from sectors like pharma. This ‘try-before-you-buy’ approach can provide companies and investors with confidence to then develop their own production facilities or find the right co-manufacturing partners.

Moreover, she continued, digital technologies can help bring down the cost and validate processes, removing some of the trial-and-error. “You can do computational modelling of your reactors before you get to them,” Armitage suggested, pointing to software developments in areas like digital twins.

Companies looking to scale their novel technologies also need to consider the end-product. “Downstream processing can be very costly. It’s really important to consider what the ultimate fit will be of your product,” the industry consultant advised.

Striving for price parity

This cost element is a very important issue for novel protein developers with an ambition to disrupt the long-established animal agricultural sector.

Leveraging economies of scale can bring down unit costs, moving novel alternative proteins towards price parity with their animal-based counterparts, it is hoped. “It’s about economies of scale, the more we produce, the cheaper it’ll become,” explained Armitage.

Achieving this will be an important tipping point for the novel food sector, according to Berger, who predicted precision fermentation and cultivated proteins could secure 20% consumer acceptance if they cost the same, or less, than conventional meat.

Brandes believes that this ambition isn't out of reach, suggesting novel protein makers are rapidly moving towards achieving cost parity. “It’s not a case of cost parity by 2030. We’re already partly there for some of the tech,” he suggested.

MycoTechnology’s experience stands as case in point, according to Hahn.

Discussing the firm’s plans to open the Oman facility, which will leverage dates that would otherwise be wasted as a feedstock for its fermented protein ingredient, the group’s chief executive was confident they will reach price parity with animal-based protein.

“It comes down to throughput, the grams per litre, per day… We’ve been very fortunate to figure out the tech that gave us a whole new generation of food.”