Food production accounts for an estimated 30% of global energy consumption, with around 70% of that being consumed after the farm. Sustainability goals have already made reducing energy consumption a priority for the food industry. Now, soaring energy costs are adding economic urgency to that drive.

René Floris, Food Research Division Manager at NIZO and member of the FoodNavigator Advisory Panel, asks Luanga Nchari, senior scientist in food process optimisation at NIZO, why food processing consumes so much energy and how vital energy savings can be achieved.

René Floris: Why does food processing consumes so much energy?

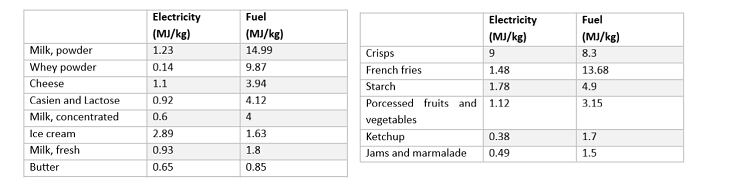

Luanga Nchari: The food processing industry needs energy for heating and cooling foods, as well as to power the massive pieces of equipment needed to produce food on an industrial scale. But the most energy intensive food products are those that require thermal processes – for example powders and fried foods. Drying, in particular, uses a lot of energy. For example, a typical spray dryer uses tens of megajoules per kilogram of product.

RF: So, we can cut energy consumption by finding alternatives to spray drying?

LN: Certainly, some industries are looking at replacing spray drying with less energy-intensive alternatives like drum drying. But it isn’t quite as simple as that. Spray drying is popular in the industry as it produces powders with very good functionality and food product producers are used to the performance you get with spray-dried ingredients. Replacing spray drying completely could mean thousands of products would need to be reformulated and new processes developed – and that would take a long time to have an impact on overall energy consumption.

However, spray drying is one of the most energy-intensive processing steps – and there are potentially big savings to be made by improving its energy efficiency.

RF: How do we make spray drying more energy efficient?

LN: In a food production process, spray dryers are fed with a liquid that contains solid matter. The higher the concentration of solids in the feed liquid the less work the spray dryer has to do. The concentration of solids can be easily increased through evaporation, which is already a common step in many food production processes. As spray dryers use around 10 to 20 times as much energy as evaporators to remove the same amount of water, there is potential for very significant energy savings. And, as the powder is still ultimately spray dried, it still has the same functionality which limits the need the changes further down the stream.

NIZO has tested this idea in our own pilot plant, and the results look very promising. In a typical process for producing dairy powders, increasing the percentage of solids in the spray dryer feed from 50% (common practice in the dairy industry) to 55% reduced the overall energy consumption by 16%. At the same time, it increased the capacity of the process by around 20%.

RF: Are there limits to how far you can take this approach?

LN: Increasing the amount of solid matter in the liquid feed will increase its viscosity, which could increase the chance of blockages in the spray dryer nozzles. However, for dairy powders, I think it should be possible to push levels of solids up to at least 60% without too many viscosity issues – which could bring very substantial energy savings.

The picture is a more complicated for plant-based ingredients as plant proteins are typically much less soluble than animal proteins. As a result, feed liquids for plant protein ingredients become more viscous at much lower concentrations of solid matter and are typically limited to around 15-20% solid matter before blockages become a problem.

RF: What, then, are the options for more energy-efficient plant-based ingredients?

LN: Plant-based ingredient manufacturers can access the energy savings that come with higher solids levels in sprayer dryer feeds if they can find ways to overcome the viscosity issues. Careful selection and design of extraction techniques and processing steps prior to drying can have a big impact on viscosity. For example, for some plant proteins, changing from acid precipitation to ultrafiltration can increase the level of solids by 8% while keeping the viscosity the same.

However, there are no “one size fits all” solutions here: an extraction technique or processing step that reduces viscosity in one ingredient may not have the same effect in another. So, each case has to be explored individually and, with the huge potential for interaction between processing steps, robust process modelling is a valuable tool. Modelling allows you to try out changes and see their impact without slowing down production, and with the right tools you can even optimise whole processes for energy consumption.

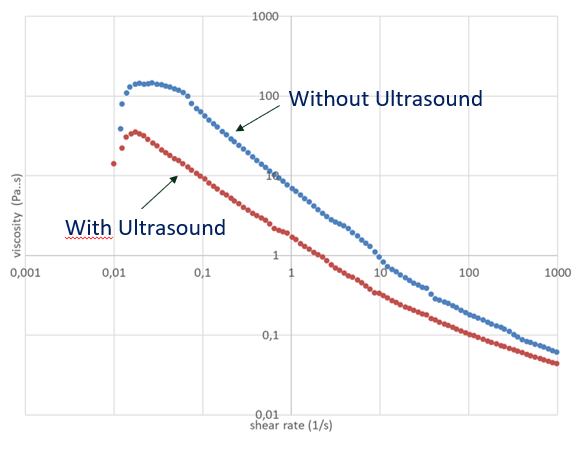

There are also technological solutions that could be used to reduce the viscosity of spray dryer feeds. One such option is ultrasound. Our research at NIZO has shown that passing a small amount of ultrasound energy through the feed liquid just before it enters the spray dryer nozzle temporarily reduces the viscosity, allowing solid levels to be increased by around 3% without blocking the nozzles. That could reduce overall energy consumption by around 6-10%. Combine that with optimised pre-drying processing, and the possible energy savings become very significant.

RF: Are there other areas where the food processing industry can save energy?

LN: Of course, it is possible to tweak almost every process in food production to cut energy consumption. But it isn’t always clear if the benefits of all that effort will be worthwhile. This is another area where process modelling is useful: identifying which changes will bring the biggest energy savings without harming the overall performance of the process.

One area that is often overlooked, though, is the cleaning of process lines. Process cleaning typically consumes up to 10% of the overall energy budget for a process. However, driven by an understandable “safety first” mentality, most cleaning plans for food production lines are too intensive and extensive – leading to unnecessary production stoppages as well as excess energy and water usage. In one example, by using sensors and reorganising the cleaning process, we found that cleaning time could be reduced by around 4 hours – essentially halving the cleaning time while achieving the same performance in terms of fouling removal. That shows massive potential for energy savings while also increasing uptime and, hence, possible turnover.

The food industry is a major consumer of energy and reducing the industry’s energy consumption long-term is an essential step in creating a more sustainable food chain. With energy prices already worryingly high – and predicted by many to rise even further – the economics of the industry are changing, and companies need to address their energy consumption as a matter of business survival, accelerating the transition to greater energy efficiency.

In our next article, we will look at developments in the field of meat replacements.