Chocolate is one of the world’s most popular flavours, perhaps second only to vanilla. This makes cocoa powder a favoured ingredient in many food products, including UHT dairy and dairy alternative drinks. While bacteria-related spoilage for these products is rare, reducing food waste is a concern for every player in the food production chain.

René Floris, NIZO Food Research Division Manager and member of the FoodNavigator expert advisory panel, asks Robyn Eijlander, Microbiology and Food Safety expert at NIZO, about the challenges, and how a consortium of cocoa suppliers, cocoa buyers and technology providers is helping get to the root of the matter, using a holistic, science-based approach.

René Floris: What challenges do food companies face when working with cocoa powder?

Robyn Eijlander: Cocoa powder has a number of unique characteristics that can make it challenging to work with. It is hydrophobic, so it doesn’t fully hydrate when mixed with water. You have to mix the powder with a small amount of liquid first to form a slurry, then combine the slurry with the rest of the liquid. But there is still a risk that tiny lumps or voids will stay dry. Cocoa powder also contains starch, so at very high temperatures it can gel, which impacts hydration, as well.

Furthermore, there is evidence from food manufacturers that bacterial spores in cocoa powder can occasionally cause spoilage in UHT liquid products. This is an unexpected and unpredictable result, however, because cocoa powder generally contains very low levels of highly heat-resistant bacterial spores that could potentially survive the thermal processes. The unpredictability makes it difficult for manufacturers to assess the risks, and optimise processes.

To solve this challenge, we have to look at the microbiology, powder physiology and processing, which requires cooperation from the cocoa powder suppliers, process technology providers and cocoa buyers, i.e., the food manufacturers.

RF: How do the bacterial spores get into cocoa powder?

RE: Part of the processing of cocoa beans is natural fermentation, which gives chocolate its lovely and well-appreciated flavour. This fermentation takes place on-site at the small cocoa farms scattered across Africa, South America and Indonesia. The presence of bacterial spores is an inevitable result of this process.

These bacterial spores are resistant to heat, acidification, etc., so they may survive the cocoa powder manufacturing process, and even the UHT beverage manufacturing process. Then, under the ‘right’ conditions, they can germinate and become metabolically active again, spoiling the product. The two most predominant spore-forming bacteria found in cocoa powder are Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis, which are notorious for a large strain-to-strain variety in spore heat resistance. Simply identifying the species therefore doesn’t predict the risk of potential spoilage.

RF: How can the bacterial spores be inactivated, to prevent spoilage risk?

RE: Bacterial spores are much more resistant to dry heat than to wet heat. If there are dry lumps in the cocoa slurry, spores within them would not be fully hydrated, and could survive the UHT treatment. Thus, to ensure full hydration of the spores, the cocoa powder particles should be adequately hydrated before the heat treatments.

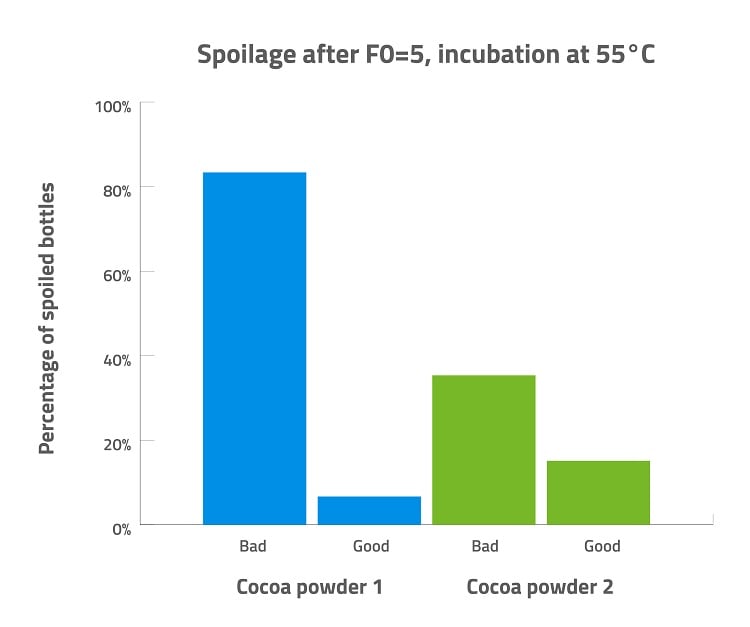

To better understand the relationship between hydration and spoilage, an industrial consortium made up of cocoa-producing companies, cocoa-buying companies, a technology provider and NIZO as an independent food research partner, carried out a joint industrial research project. In a proof-of-principle pilot experiment, two different cocoa powders were exposed to diverse hydration and thermal processing conditions. These cocoa powders were specially selected for the purposes of this study: one had a high concentration of bacterial spores (this powder is not commercially available), and one had low spore concentrations, but had been associated with a real spoilage incident.

Cocoa slurries of each sample were prepared using either a ‘bad’ (cold temperature, minimal time in the high shear pump) or a ‘good’ (20 minutes of high shear mixing at a higher heat) hydration process. The slurries were then used to make UHT-treated chocolate milk, which was stored in bottles in an incubator to allow for germination and outgrowth of surviving spores.

The samples that went through the ‘good’ hydration process showed considerably less spoilage than the samples using the ‘bad’ process. The results proved that the level of hydration of cocoa during slurry preparation is crucial in ensuring the inactivation of bacterial spores during thermal processing, and that the most important parameter to achieve this effective hydration is temperature (assuming ‘high shear’: very forceful mixing processes using high-speed impellers).

RF: What is the role of the industrial consortium, and what is the added value of this joint approach?

RE: The pre-competitive consortium is working together to ensure positive, constructive communication between cocoa suppliers, cocoa buyers and technology providers, to align best practices, and to find ways to reduce spore-related spoilage risk in UHT drinks containing cocoa powder. It is clear that no single factor is fully responsible for the rare spoilage events, so a holistic, multidisciplinary approach supported by scientific objective analysis is needed.

The first work project of the consortium focused on the challenges of enumerating and identifying bacterial spores in cocoa powders. Reliable detection of the number of bacterial spores in cocoa powder using standard plating techniques is complicated by the antimicrobial effect, poor wettability and dark colour of cocoa.

The consortium developed a science-based reference method for determining spore concentrations in cocoa powders. The peer-reviewed paper provides a practical and optimised approach, along with expert insights on how to interpret the results.

The second work project focussed on the processing of cocoa for the production of UHT chocolate milk, particularly the degree of hydration and its impact on spoilage by surviving spores after thermal processing. The proof-of-principle hydration pilot was part of this phase, and incorporated the learnings and developed methods from the entire project.

RF: What are the next steps for the consortium?

RE: There are still quite a few research steps needed to achieve the consortium’s goals, which we will tackle in a follow-up multidisciplinary research project. We need to further optimise the methods for measuring hydration, including defining the best settings and the limits for obtaining optimal dispersion and hydration of the cocoa powder. And we need to understand the influence and impact of properties such as fat, starch, spore counts and spore types, and of processing settings including temperature and time, cocoa concentration, soaking, etc. The consortium continues to welcome new members to participate in the investigations.

The paper ‘Enumeration and Identification of Bacterial Spores in Cocoa Powder’ is available via Open Access in The Journal of Food Protection.

In our next article, we will look at the challenges involved in developing the next generation of plant-based drinks.