Developing new formulations for familiar products is a major part of the food industry. For example, to meet consumer demands for food products with less fat, sugar and salt, or plant-based versions of animal-based favourites. But while consumers are eager for healthier, more ethical and environmentally friendly foods, they also expect the same eating enjoyment as they get from the foods they know and love. This month, I spoke to Els de Hoog, Senior Project Manager, Flavour and Texture at NIZO about how manufacturers can deliver the right sensory experience when reformulating food products.

René Floris: Why is the sensory experience such a challenge when reformulating foods?

Els de Hoog: With consumers looking for healthier food options, manufacturers are trying to reduce the levels of things like salt, sugar and fat in their products. However, these ingredients often contribute a lot more to a product than just the obvious. For example, sucrose obviously adds sweetness. But it is also a bulking agent, adding body to the product. So simply replacing sucrose with another sweetener can help to mimic the flavour of the original but will alter the texture and mouthfeel.

Moreover, sucrose delivers its sweetness intensity straightaway whereas stevia, for example, has a short delay before that intensity arrives, allowing time for other flavours to come forward. This can unbalance the overall flavour experience so that, although it has the same level of sweetness, the product doesn’t taste how the consumer expects.

This kind of “non-obvious” effect becomes both more likely and more difficult to predict as food products become more complex. With more ingredients, there is more scope for interaction between ingredients, and so any changes can have a far-reaching and often unexpected impact on the sensory experience.

RF: How can manufacturers develop “reduced” products that deliver the full sensory experience?

EdH: Food product developers today are very skilled at developing new formulations to meet specific requirements and / or customer demands. But with more complex products, it can become very challenging and may require an iterative approach.

First, you have to accurately identify the gap between your new formulation and consumers’ expectation of the product. Is it purely a taste issue or do you also need to address mouthfeel, aroma, etc? Shelf life and food quality are also important considerations, as ingredients such as salt and sugar can act as preservatives. Thinking about the consumer perception of the other benefits of your reformulated product can also help you focus on which gaps are most important to address – consumers may be willing to accept a slight change in texture or flavour if the health benefits and overall sensory experience are strong enough.

Only once you have that insight can you start to develop effective compensation strategies.

RF: What kind of compensation strategies are available to developers?

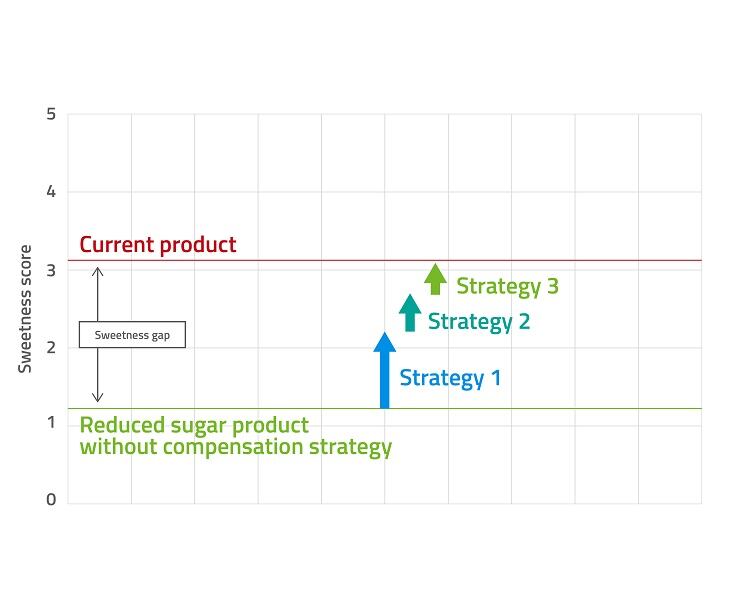

In the simplest cases, a compensation strategy could just be replacing the salt, sugar or fat with another ingredient. However, in more complex products, a single substitution is unlikely to fully close the gap and you will need to combine strategies. For example, in a reduced-sugar product you might consider using both an artificial sweetener and bulking agent as well as adding complementary aromas that enhance sweetness. You can also take advantage of the cross-modality between taste and texture, for instance, using vanilla’s “creamy” taste to improve mouthfeel in low-fat products. You may even want to consider processing steps such as fermentation to improve the product’s texture, robustness and shelf life.

Combining strategies, though, is far from straightforward. It can take a lot of in-depth understanding of the interaction between ingredients, product matrices and production process to find the right combination. And strategies that are necessary to improve one sensory area, say mouthfeel, can sometimes actually widen the gap in another, such as taste. So, there can be a huge amount of trial and error involved in developing and assessing new formulations.

RF: Is there a way to speed up the process?

EdH: Yes, there are a number of tools available – both to better identify the sensory gap and to bridge it.

For example, food manufacturers are already familiar with consumer testing panels for evaluating the overall performance of new product formulations. But this just tells you if consumers like the (nearly) final product. At NIZO, we have found that an analytical sensory panel can be a very useful tool in the earlier development stages. These expert tasters are able to differentiate between taste and mouthfeel, helping to better understand the sensory gap and identify the priorities required to successfully bridge it.

There are also various screening technologies that allow you to assess potential strategies without having to develop a full product concept. Tribology experiments can be used to objectively study mouthfeel in the lab by sufficiently mimicking the complex interaction between food components, saliva and the surfaces of the mouth – something we have done for a number of foods.

Similarly, olfactometry, where an expert taster tastes the basic “reduced” formulation in the presence of various potential compensating aromas, can be used to explore how different aromas affect the perception of the product. This enables rapid screening of different compensation strategies and the selection of promising candidates/combinations for further study. This technology was recently used to identify three aroma fractions that could act as label-free taste boosters in bacon and gammon, helping a manufacturer to reduce salt levels by 30% while maintaining sales – cutting 400 tonnes of salt per year in the UK alone.

Next month, we will discuss challenges and solutions for scaling up food and ingredient production processes.