René Floris: Why is controlling pathogens and spoilers a concern for the food industry?

Marjon Wells-Bennik: Foodborne outbreaks related to pathogens such as Listeria, Salmonella, Bacillus cereus and others can cause harm to consumers, damage to brands, and liability issues for the companies involved. Furthermore, contamination with micro-organisms that cause spoilage can result in high costs and food waste. Whenever you are developing a new product or modifying an existing one, microbial contamination is a risk. Even small changes – adding an ingredient or nutrient, reducing salt or sugar, reducing heat during processing – can open the door to pathogens and spoilers.

Listeria monocytogenes, for example, can cause serious illness, with a 20-30% mortality rate. This bacterium is inactivated by heat, but if the heated product is contaminated after processing and supports growth, it can pose a health risk. Other micro-organisms, particularly spore formers, are hardier, thriving in different conditions. If you wait to address the risk of microbes in your product, you could find yourself searching for solutions, reformulating ingredients, or modifying processing when you are already half-way through development.

But if you include safety early in product development, alongside developing the product characteristics, you can more cost-efficiently address the possible pathogen risks, and design safety into your product from the ground up.

RF: What are we looking for in the products to ensure microbial safety?

MW-B: With both pathogens and spoilers, you have to consider two aspects. Firstly, presence/absence: does the product contain any micro-organisms of concern? Secondly, the potential for growth: could the product support growth of the micro-organism?

This means you must control pathogens and spoilers both during and post-processing. By controlling your manufacturing process, you can ensure that a safe, sterile product comes off the line. But if it then comes into contact with pathogens or spoilers post-processing, you need to know the microbes cannot grow.

Take the example of Listeria, where there is a particular concern regarding post-processing contamination of ready-to-eat food products, such as cheese, which the consumer will eat without further heating. EC regulation 2073/2005 specifies that, if your ready-to-eat product supports growth of L. monocytogenes, there may be no Listeria present when it leaves the production facility. Even if your product does not support Listeria growth, Listeria levels must remain below 100 colony-forming units per gram (cfu/g) throughout the product’s shelf-life.

And Listeria is only one of many pathogens that can contaminate dairy and plant-based products.

RF: What role can modelling play in food product safety?

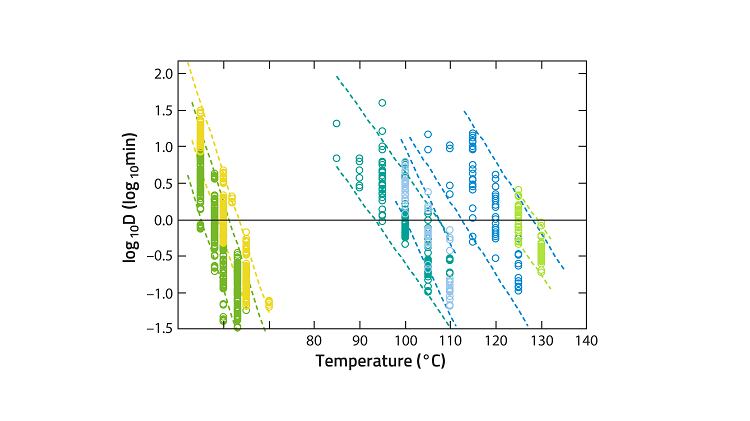

MW-B: Modelling can be extremely useful at different stages of product development. At the very early product design stages, you can use in silico predictive modelling to map out potential bacterial risks by calculating microbial inactivation (Figure 1) and growth. The mapping takes into account the boundaries of the product you want to make: everything from the processing conditions to the desired characteristics, such as the water activity, the pH, and even how your product will be stored by the consumer: refrigerator, freezer, in ambient temperatures, etc.

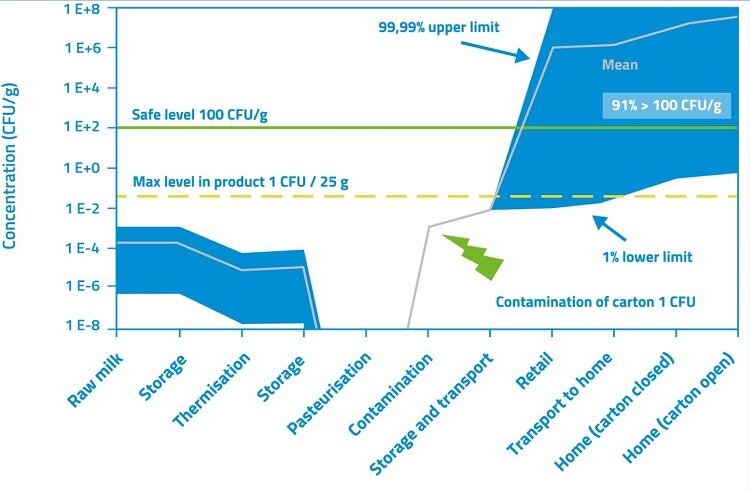

Once formulations are developed, models can more precisely identify the risks. Using quantitative microbiological risk assessments, you can look at the effect of inactivation and growth together, to see, for example, the survival rate of a pathogen after heating, and what that means for potential outgrowth during production or even in the finished product (Figure 2).

RF: How do you test the actual products?

MW-B: To test real products, you can start by producing small batches of the product with different formulations, and assessing various microbial contaminants of concern using high-throughput methods at micro scale. But of course, food manufacturing is done in big batches, so you need to scale up, and then perform full-blown so-called challenge tests, to validate the outcome of the risk assessment and the micro scale tests. By using this approach, only limited numbers of pilot scale batches need to be produced and tested before a product can be introduced to the market. At each stage, you have to keep in mind that small changes anywhere in the chain can change the risks, so take it step by step.

As living things, micro-organisms show a lot of diversity of characteristics, even within species. This may have an impact on challenge tests - if you test your product formulation using a ‘middle of the road’ strain, you may see no growth, and feel secure. But another strain might be resistant to the formulation and processing you have developed, and be able to grow.

It can be helpful to run ‘worst-case’ scenarios. So, if you are working on a product that is high in salt, you pick pathogenic strains that are salt-resistant. If the product is acidic, you can use acid-resistant strains, etc. But you need a large culture collection of bacteria to create this ‘worst possible’ mix, and then test it on the product.

RF: Are the pathogen and spoilage risks the same for dairy versus plant-based products?

MW-B: We have a long history of dealing with pathogens and spoilers in dairy, and we know a lot about their sources, their levels in raw milk, and how they react. Also, all dairy products are based on milk, so there is always the same type of fat, sugar, etc. Even so, every change to your product can present a risk. For example, in UHT dairy products, most spores present in raw milk are inactivated by the high heat treatment. But if you add a new ingredient or nutrient to the milk, you may create an environment that now triggers germination of spores and conditions that support growth.

For plant-based products, (Figure 3) there are many more unknowns and variables regarding the types and levels of micro-organisms and their behaviours. Furthermore, companies are trying out many, often innovative, approaches to create plant-based alternatives that offer the same mouthfeel and structure, taste, look, etc. as dairy versions. It is critical to understand the effect of processing and the selection of ingredients and formulations to control pathogens and spoilers.

And every plant-based product has its own potential issues: with a non-dairy cream, it might be heating; for yoghurt-like products perhaps challenges in the fermentation process; for cheese alternatives, maybe control of contaminants during storage… Each new product creates a unique pathogen or spoilage risk. That is why it makes sense to design-in safety from the beginning so that you don’t discover a health or spoilage risk later on that sends you back to the drawing board.

So far, we have focussed our columns around the protein transition. In our next column, we will discuss the potential of using proteins produced by single cell micro-organisms as an additional protein source in the protein transition.