At the recent #SacktheSachet campaign launch in London, which revealed that as many as 855bn plastic sachets are used every year by food and home care brands and which urged the food and beverage sector to take responsibility for the problem of plastic sachet pollution, Lapping explained that recycling wasn’t the only solution to the plastic pollution problem.

“People seem to think we can recycle our way out of this problem. That's simply not true. Three billion people on this planet have no waste management system, and they are not going to have one tomorrow. They [in the developing world] don't have sufficient healthcare, education and a whole lot of other things, so waste management is quite low on their priority list.”

The Ellen Macarthur Foundation, meanwhile, has just updated the amount of plastic pollution in our oceans at 12m million tonnes per year and rising. "We need to do something, and we need to do it better,” he added. “People want to help, but they are very confused, and need practical solutions to find a way forward.”

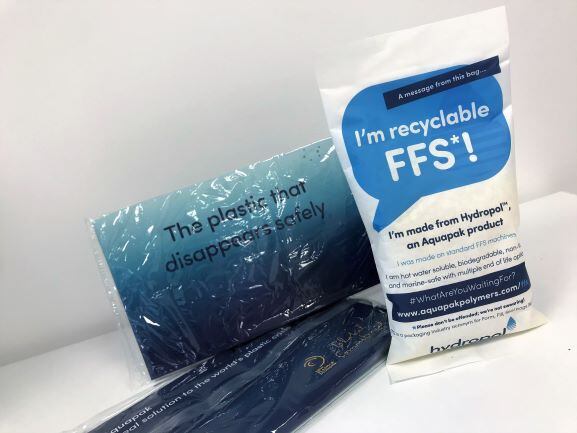

One solution available to the food sector is to use PVOH-based packaging. PVOH is a material generally recognised as being soluble in water, marine safe and non-toxic, and one that is both 100% recyclable and 100% biodegradable. So if, in the worst-case scenario, your packaging leaks into the environment after usage, it will disappear naturally by dissolving and biodegrading, without breaking down into harmful microplastics, in the ocean, fresh water or on land.

Cost has been a barrier

Sounds too good to be true – but the main reason why this polymer has remained the unsung hero of the plastic world up to now is that it is a very difficult material to process. Aquapak has, however, developed a formulation of PVOH as a fully thermo processable resin pellet, which can be processed by the packaging converters in industry standard packaging lines. Meanwhile, the fact that PVOH is hydrophilic (water loving) means that it will not be a moisture barrier on its own, but this can be overcome, according to Aquapak, by combining it with other single materials such as paper, whilst maintaining the end of life benefits of the whole packaging solution.

Consumers are demanding solutions to plastic pollution

The CEO of PVOH polymer manufacturer Aquapak is optimistic that rising public consciousness of plastic pollution can help this material overcome its challenges as more food brands look to innovate their packaging solutions and better connect with the demands of their customers.

PVOH, explains Lapping, is an incredibly useful polymer in its own right, being a barrier to oxygen, grease, oil and fat, 2.5 times stronger than HDPE and naturally anti-static, with good surface energy for printing. It forms strong heat seals, and can be formed into pouches on its own, or in combinations with plastic or paper substrates, in standard vacuum, form, fill and seal operations.

“Against the cheapest, most ubiquitously available polymer on the market, such as polyethylene, which most food packagers try and use, PVOH is currently about four times more expensive,” he told FoodNavigator. “If you're measuring it against a biopolymer, its costs are roughly similar. So, it's different polymers for different applications and functionality at different prices.”

The most practical use in the food industry, he reckons, is to combine it with other materials to make them easier to recycle. Take a sandwich pack, for example. Whilst the board element of sandwich packaging can easily be recycled, customers and processors can experience difficulty separating the cardboard from the see-through film part of the pack. That issue could potentially be resolved with a film made from PVOH: this would dissolve, while the paper part of the packaging is recovered and recycled.

Should industry innovate or abandon plastic?

Some disagree that innovation is a solution to plastic pollution, preferring instead efforts that reduce the need for packaging in the first place, or promoting better systems to capture and recycle packaging waste.

But Lapping believes technology innovation in materials are a key part of the solution, and is urging industry to explore more environmentally sustainable forms of plastic. “Even if we were to have the best capture and recycle system, which we don't, there's always going to be leakage,” he observed. “For that eventuality, we need the thinking to be that there are new materials out there which can help you design a better range of possibilities at end of life than you've got now. It's not about going from poor to perfection in one leap.”

The point about PVOH based packaging is to offer something that gives peace of mind at end of life.

“Our polymer, at the end of life, gives you all those options: you can either recycle it; it can be anaerobically digested in a Waste To Energy facility without leaving any microplastics in the digestate; or you can compost it. In the worst case, if it gets into the environment it's going to disappear safety and leave no trace. If it's eaten by sea life before beings broken down, it's going to be safely digested, unlike hydrophobic polymers.”

Aquapak makes a range of different PVOH blends, meaning the time it takes to dissolve in water can vary. Hot water soluble grades, for example, are more robust at most ambient temperatures, but dissolve rapidly at temperatures above 70℃. Warm water soluble grades will break-down rapidly at temperatures above 40℃. “So, in the worst case and our 70℃ one ends up in the coldest sea it would probably take two to three years to completely disappear. In a warmer sea, the lower temperature version will probably go within six months.”