The Scottish Salmon Producers Association (SSPO), the industry trade body, commissioned independent research from 4 Consulting which highlighted the ‘vital’ economic and social benefits that the industry provides in some of the county's most remote rural economies.

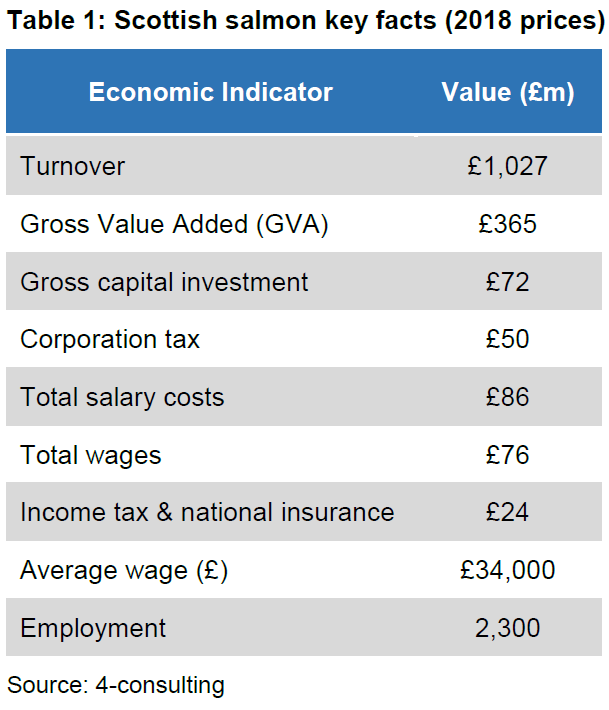

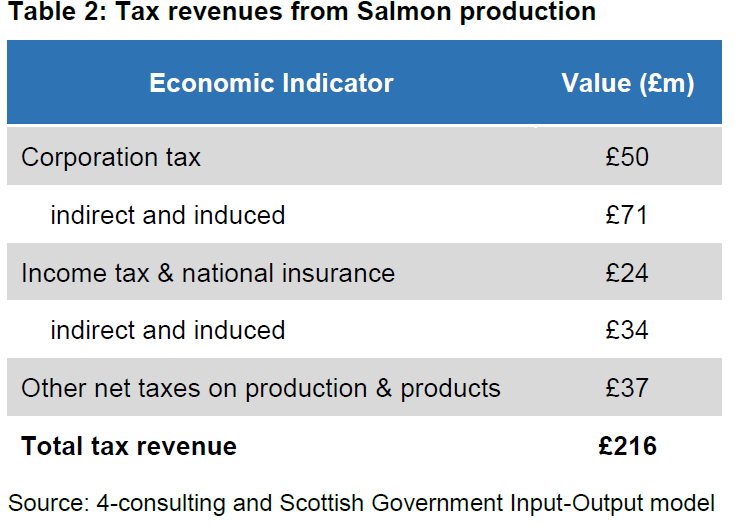

The Scottish salmon farming industry generated more than £1 billion (€1.2 billion) in turnover last year, according to the research. But it suggested the total impact could be double that, and nearer £2 billion, once spending through wages and taxes is taken into account.

The industry also contributes £50 million in corporation tax and £76 million in wages, said the report. The average wage for workers in the Scottish salmon industry is around £34,000 per annum.

It also has around 250 employees that are engaged in modern apprenticeships each year. Currently 82% of those leaving aquaculture modern apprenticeships achieve qualifications compared to 76% in food and drink operations and 75% for all modern apprenticeships.

Hamish Macdonell, director of strategic engagement at the SSPO, said: “It should come as no surprise that the Scottish farmed salmon sector contributes a huge amount to the economy, but what these new figures reveal is quite how big that contribution is.”

“An overall economic impact of more than £2bn represents a major benefit to the Scottish economy in itself but with average salaries of £34,000 for the 2,300 people directly employed, the sector is injecting extremely valuable resources into some of Scotland's most fragile, sparsely populated, rural areas as well."

Swamped by criticism

However, the negative impacts of salmon farming can’t be ignored, according to campaigners.

Complaints about the industry are well documented. Campaigners say effluent from farms causes pollution and that sea-lice infestations and escapes at salmon farms have had a devastating impact on wild salmon and sea trout populations.

Dr Sam Collin, Marine Planning Manager at the Scottish Wildlife Trust, told FoodNavigator: “We recognise the economic importance of salmon farming to fragile rural communities but the real challenge is to develop an economically successful industry that also works in harmony with the natural environment.

“At the moment the cost to the environment, such as impacts on wild salmon or marine ecosystems from sea lice and farm waste, is harder to quantify. Ignoring these impacts can exaggerate the benefits of salmon farming.

“To develop a truly sustainable aquaculture industry in Scotland we must consider all of the social, economic and environmental costs and benefits collectively, rather than focus on one aspect in isolation.”

Wild salmon levels at ‘crisis point’

Illustrating the challenge for the salmon farming industry was a report released this week by Fisheries Management Scotland. This claimed that levels of wild salmon in Scotland are at their lowest since records began in 1952. It said the fish is now at “crisis point” and called for more to be done to preserve the species.

The report noted infestations of sea lice have hit both wild numbers and farmed salmon stocks. For instance, last month, Scotland’s biggest salmon farmer Mowi (formerly called Marine Harvest) revealed the amount of gutted salmon it produced from Scottish waters fell by 36% in 12 months, with infestations of sea lice and disease blamed.

Other factors are at play, however. Fisheries Management Scotland also blamed falling salmon numbers on water degradation, management infrastructure such as dams, along with open-net salmon farms, climate change and soaring demand for salmon.

An SSPO spokesperson told FoodNavigator that the declining number of wild salmon was down to “a myriad of factors” including over-exploitation, climate change and rising sea water temperatures. But he added that sea lice infestations at farms and its impact on wild salmon levels “is something we’re conscious of and it’s not something we want to ignore”.

He stressed, too, that the industry is becoming increasingly transparent. “We are aware of the criticisms, and as an industry we’re taking action wherever possible to limit the environmental impact from farming and we’re working towards creating a fully sustainable industry at all levels.”

Concerns over the environmental impacts of salmon farming in Scotland have been repeatedly raised for many years:

- 1990 – Marine Salmon Farming in Scotland by Scottish Wildlife and Countryside Link

- 2001 – Bitter Harvest: a call for reform in Scottish aquaculture by WWF

- 2002 – Review and Synthesis of the environmental impacts of aquaculture by the Scottish Association of Marine Science

- 2012 – the Scottish Wildlife Trust provided oral and written evidence to inform the Aquaculture and Fisheries (Scotland) Bill

- 2016 – Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST) raise concerns to Scottish Ministers over the expansion of salmon farming in Lamlash bay

- 2017 – Salmon and Trout Conservation Scotland petition, which resulted in the Scottish Parliament inquiry into salmon farming

Source: The Scottish Wildlife Trust

A new era of collaboration?

The salmon farming industry and angling community (not traditional allies) are in a “new era of collaboration and cooperation”, he said. “We want to work with people and there are various projects which are under way at the moment.”

One of these is a Mowi’s ‘smolt to adult supplementation programme’ at the Drimsallie Hatchery in the north-west Highlands, which aims to help boost stocks of wild salmon.

Jon Gibb, director of the Lochaber District Salmon Fishery Board, explained how the initiative works. “The idea is that we trap migrating wild salmon smolts in the rivers – over 95% of which would die anyway at sea – and transfer these wild fish to Mowi sea cages. Mowi would then grow the wild salmon smolts to adult stage and then, once they reach maturity, we would release them directly back into spawning burns. The introduced salmon would spawn naturally in the wild and this would guarantee the numbers of juvenile fish going to sea in future generations. This is pioneering work and has never been tried in Scotland before.”

Sea lice? Seals? What’s behind the plummeting salmon numbers?

“Back in the 1990s I would have agreed that the biggest factor affecting wild salmon was rising levels of sea lice and escapes from fish farms,” according to Jon Gibb, director of the Lochaber District Salmon Fishery Board Gibb.

But changes in the freshwater and oceanic ecosystems are having a greater impact today. “There is simply no denying that the sea temperature is rising,” he said.

As well as encouraging sea lice, this makes it more difficult for wild salmon to find their natural food.

“Wild salmon feed off krill, shrimp and sand eels, which prefer to live in colder water. A direct consequence of rising sea temperatures is that wild salmon are having to swim further north to find food, sometimes without success. Wild salmon are having to adapt and dive deeper to find food on the seabed which can result in them being attacked by parasites. We are currently experiencing an infestation of nematode worms in fish which are often thin and under-nourished. Other factors include scallop dredgers which destroy vital marine habitats but also other burgeoning wildlife, be that seals or birds that feed off fish.”

The ‘environment vs economy’ debate is playing out in Iceland too

The experiences of the Scottish salmon industry may have salutary lessons for Iceland, which is pushing ahead with plans to expand open net salmon farming in the face of criticism from environmental groups and scientists.

Iceland’s parliament will soon vote on a bill that could allow the world’s biggest aquaculture companies to farm vast amounts of salmon in open nets.

If the plans get the go-ahead the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority expects salmon production to reach 20,000 tonnes this year, up nearly 50% from the 13,448 tonnes produced in 2018.

The government aims to become a significant player in salmon farming and in doing so hopes to restore prosperity to many rural economies. The plans could provide hundreds of new jobs in the country’s deprived Westfjords region. But environmental groups fear the plans risk decimating wild salmon populations.