The food industry has entered a new era of transparency. Food companies are scrutinised on issues ranging from their use of processed ingredients to sustainability standards in their supply chains. This is placing the industrial food production model – which for the past 60 years has made processed food progressively more abundant and cheaper in western societies - under pressure.

Vanilla ice cream with no vanilla… or cream

A higher level of interest and awareness are among the factors underpinning the clean label trend. Analysis of the ingredients list has definitively entered mainstream discourse.

Only last week, UK consumer group Which? released an investigation into the ingredients used to make various vanilla ice cream products.

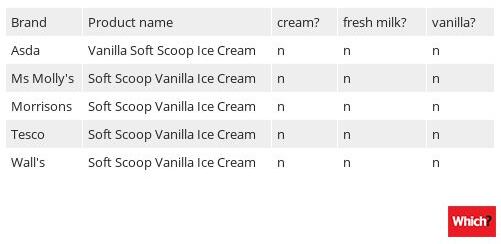

The results made national headlines: one in five ice creams tested contained no cream, fresh milk or vanilla. On the naughty list were Asda, Ms Molly’s, Morrisons, Tesco and Unilever’s Wall’s.

In contrast, Which? noted 12 ice creams did contain all three of the traditional ingredients. Unsurprisingly, all of these brands have more of a premium positioning – and a price that reflects this.

Which? analysis of ice cream ingredients

The cost of clean label

Unilever, which also owns Ben & Jerry’s and Cart D’Or, has brands featured at the top and bottom of the ‘ingredients league table’. This reflects the position of the company’s brands across the value spectrum.

“We have a range of ice creams to provide our fans with a wide choice to meet different tastes and preferences,” a spokesperson for the company told FoodNavigator. “Our Wall’s Soft Scoop Vanilla Ice Cream is a family ice cream that is easy to scoop and can be enjoyed straight from the freezer and includes concentrated skimmed milk, which comes from fresh cow’s milk, as well as vanilla flavouring. All of the ingredients are clearly labelled on our packs and meet the ice cream regulatory standards.”

Before 2015, a product labelled ‘ice cream’ in the UK had to contain at least 5% dairy fat and 2.5% milk protein. However, since the introduction of the Food Information Regulations in 2015, these rules no longer apply.

A product labelled as ‘dairy ice cream’ must contain at least 5% fat, some protein from a dairy source and no vegetable fats. But there are no requirements to call a product ‘ice cream’.

This opens the door to product reformulation to reduce fat and means that vegan products can be described as ice cream. According to Which? it also means “cheaper products made with lower-quality ingredients can also be labelled as ice cream”.

But if products are going to be cheap, the ingredients that go into them have to reflect this.

A shortage of supply has pushed up the price of vanilla. Data from Mintec reveals that the price of vanilla increased to more than US$600 (€518) per kilogram this year, making it more expensive than silver. Likewise, at €1.58 per kg, skimmed milk powder is a cheaper ingredient than cream, which is currently trading at around €2.80 per kg.

Clean label ingredients are more expensive and this has to be reflected in consumer prices. As one supplier of synthetic ingredients suggested at a trade show last year, there will always be a demand for artificial ingredients as long as there is a demand for cheap food.

Delivering on consumer choice?

Consumers, the argument goes, should be afforded the choice of buying cheap food. But for this to truly be a choice relies on two premises: Firstly, that they understand the trade-off and, secondly, that they have other options.

Increasingly, many consumers are developing an appreciation of what goes into the foods they buy.

This is reflected in the higher growth areas of the food sector. Organic sales in Europe are growing, food makers are cleaning up their ingredients lists, healthy or better-for-you is seen as a key trend and smaller mission-based brands that can tell a strong story are stealing market share from ‘big food’.

But there is a socio-economic aspect to this debate. Access to nutritional education is not equal for all consumer segments, meaning that disadvantaged consumers are less likely to be making informed choices.

Likewise, if cheap food equates to inexpensive, often less healthy, filler ingredients and artificial additives, are poorer consumers priced into a corner where their choice is taken away?