Providing half of the world’s population – over 3.5 billion people – with 60 to 70% of their daily calories and over two billion people with their main source of livelihood, rice is of massive importance.

Its cultivation, however, can also have a massively negative impact on both the environment and those who grow it.

“Rice-based systems are nexus of all complex food problems,” the co-founder and joint CEO of US company Lotus Foods, Caryl Levine, told delegates at the Sustainable Food Summit in Amsterdam last week. “Conventional rice production is just not sustainable. It uses between one quarter and one third of the world’s fresh water and there is a huge cost of input, which means many farmers are burdened with debt.

“There is an especially high impact on women. They do most of the physical activity in the paddy fields where they are exposed to leeches, parasites and water-borne diseases. After years of harvesting rice, many are unable to walk upright and so are continually bent over. This is not acceptable.”

Thriving, not surviving

Lotus Foods therefore works with farmers to find heirloom rice varieties that are cultivated according to its trademarked ‘More Crop per Drop’ technique, an organic version of a sustainable growing process called System of Rice Intensification (SRI).

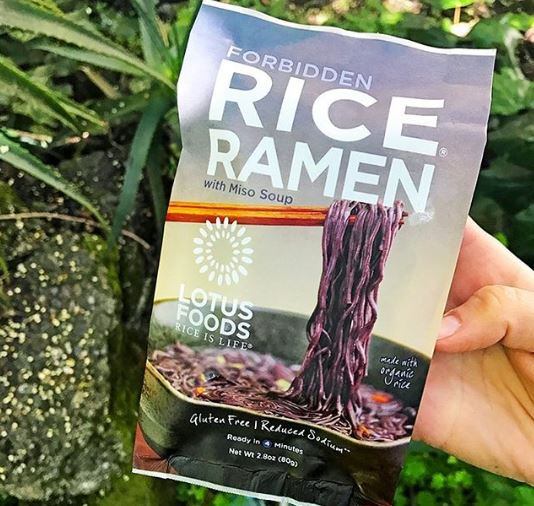

Founded in 1995 when Caryl Levine and Ken Lee began importing black rice to the US after trying it during their travels around China, its range includes Mekong Flower rice, so-called because of its floral aroma; Madagascan pink rice with a cinnamon and clove aroma; black ‘Forbidden’ rice grown in Sechuan, China with a roasted nutty flavour; and red and brown volcanic rice from Java in Indonesia.

The company, which scooped up second place in Ecovia Intelligence's Sustainable Food Awards last week for being a ‘sustainable pioneer’, sells its products

online and has retail listings throughout the US.

According to the SRI method, farmers plant smaller, younger seedlings that reduces transplant shock and plant them at wider spacing in rows – rather than randomly in clumps – which minimises competition and facilitates weeding.

Farmers also keep the soil moist but not flooded, which saves water and keeps the soil healthier. “Rice is not an aquatic plant. It can survive in water but it doesn’t thrive in water,” Levine explained.

Supported by the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture (FAO) and NGOs such as Oxfam and WWF for its positive impact, SRI allows rice to be harvested upright in fields, meaning safer working conditions for the farmers.

Lotus Foods claims the some 5000 households in Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Madagascar and Thailand that supply it rice have seen a three-fold increase in yields since adopting More Crop per Drop practices, and higher income through the organic and fair trade Fair For Life premiums. Farmers also require 90% fewer seeds than conventional rice varieties, meaning savings on inputs.

“The impact of SRI is even more exciting when seen in context of global warming,” Levine added. “We are going beyond organic to promote a system that saves water, reduces methane emissions, preserves biodiversity and empowers women. I don’t know of any other farming system that does both environmental and social achievements in this way.”

The SRI techniques save Lotus Foods’ farmers around 500 million gallons of water annually and cut methane gas emissions by around 40%.

‘Doing the rice thing’

Despite the some 130,000 varieties of rice that exist in the international gene bank, recent years have seen a dramatic loss in biodiversity as countries switch to modern agricultural techniques.

According to Levine, getting Westerners “who don’t have a culture of eating rice and no awareness of coloured rice” to embrace new varieties has been a challenge. This means that new product development is an important part of Lotus Foods’ strategy to increase uptake.

In addition to selling the whole, unprocessed rice, the company manufactures flavoured rice crackers, ramen and instant noodle soups and ‘heat-and-eat’ microwaveable rice bowls.

The coloured varieties also have healthier profiles than the typical white Basmati or Thai rice.

A single 60 g serving of black Forbidden rice provides 120% of the recommended daily allowance of manganese, 35% molybdenum; 20% magnesium and 20% phosphorous, while the Jade Green rice is ‘infused’ with bamboo extract, giving a green colour and a nutrition boost.

“We want to give consumers healthier alternatives with value-added innovations – products that are not just premium but have a high nutritional value.”

Protecting biodiversity

Levine gave the example of Thailand to illustrate just how quickly crop biodiversity – essential in making farmers more adaptable to climate change – can disappear. In the 1960’s, the Thai government launched a so-called ‘green revolution’, encouraging farmers to switch to new strains of seeds that were optimised for agro-chemicals.

“Before the green revolution, Thai farmers grew around 16,000 varieties of rice. Today, they grow fewer than 37,” Levine said.

“There is good news, however,” she added. “There are still thousands of varieties and in India, there is a renewed interest in ancient varieties. Pigmented and heirloom varieties are growing in popularity.”

This interest is also growing in the Western world. In Italy, the Principato di Lucedio used non-GMO techniques to cross a Chinese black rice with a local Italian variety, producing the Venere black rice while earlier this year, researchers from Cornell University and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) developed a whole-grain red rice, called Scarlett.

“Yesterday I was in a Coop shop and saw black and red rice. You wouldn’t have seen that 20 years ago,” Levine said.