An international team led by scientists from Imperial College London and the University of Exeter have suggested that improved practice in how antifungal treatments are used, as well as the discovery of new treatments, are needed to avoid a “global collapse” in our ability to treat fungal infections.

Crop-destroying fungi are already thought to account for a loss of 20% of global crop yields each year, the researchers noted in a review paper published in the journal Science, with a further 10% loss post harvest.

Fungal threat ‘under-recognised and under-appreciated’

Professor Matthew Fisher, from the School of Public Health at Imperial and lead author of the study, said that the threat posed by growing resistance to fungicides is “under-recognised and under-appreciated”. He compared the issue to the spread of bacteria that has developed a resistance to antibiotics.

“The threat of antimicrobial resistance is well established in bacteria, but has largely been neglected in fungi,” he said.

“The scale of the problem has been, until now, under-recognised and under-appreciated, but the threat to human health and the food chain are serious and immediate.

“Fungi are a growing threat to human and crop health as new species and variants spread around the world, so it is essential that we have means to combat them. However, the very limited number of antifungal drugs means that the emergence of resistance is leading to many common fungal infections becoming incurable.”

Professor Sarah Gurr, from the University of Exeter, added: “Emerging resistance to antifungal drugs has largely gone under the radar, but without intervention, fungal conditions affecting humans, animals and plants will become increasingly difficult to counteract.”

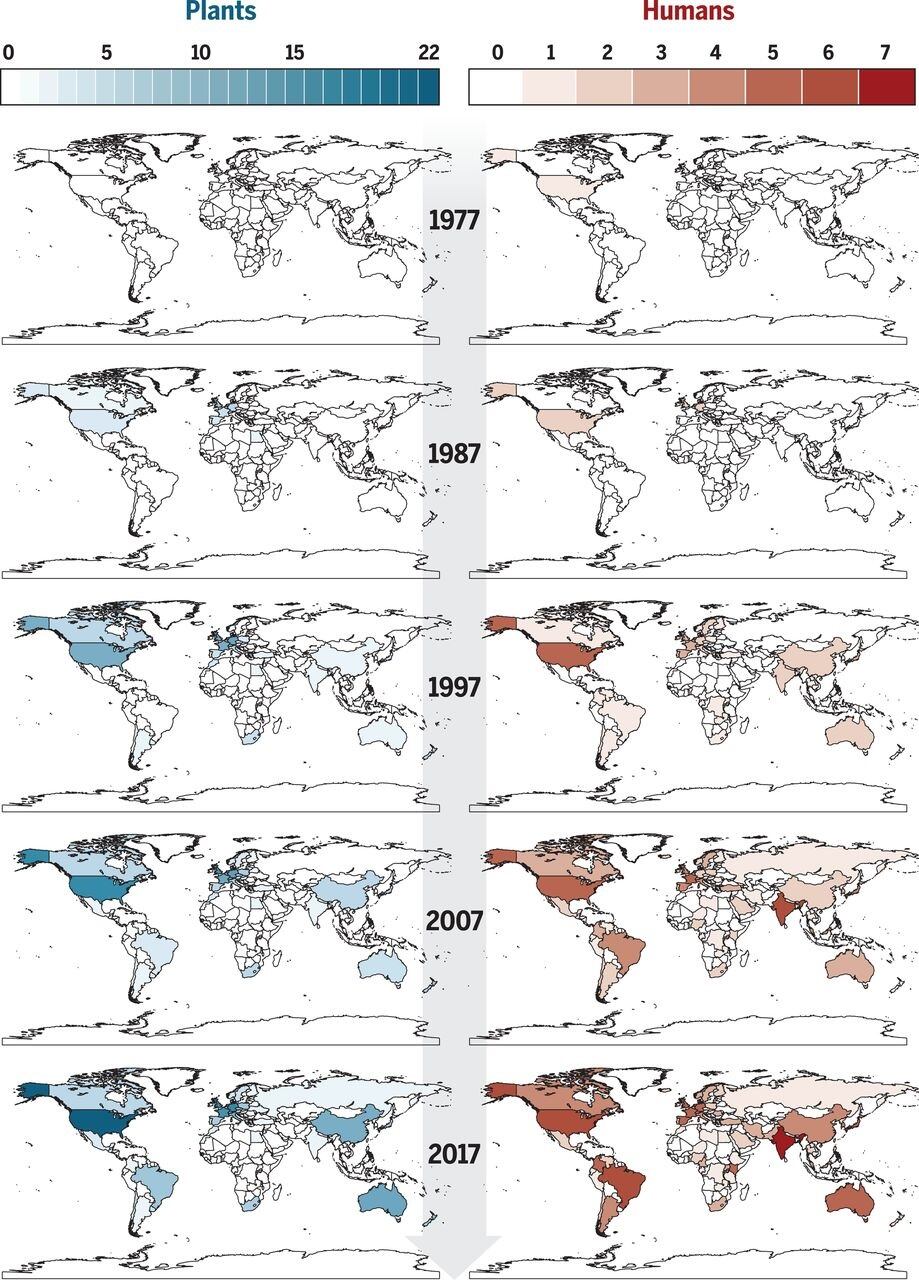

Fungal species with reported antifungal resistance, by country

Increasing colour intensity reflects a growing number of reports. The plant maps depict spatiotemporal records of resistance of crop pathogens to azoles (blue scale). The human maps depict spatiotemporal records of resistance of the pathogens A. fumigatus, C. albicans, C. auris, C. glabrata, Cryptococcus gattii, and Cryptococcus neoformans to azoles (red scale). The data are derived from peer-reviewed publications as of March 2018, reporting the occurrence of cases of resistance up to 2017.

Illustration: CHARLOTTE GURR, Adapted by K. KHOLOSKI

Resistance linked to modern food system

The researchers linked the growing risk presented by fungal outbreaks to developments in the modern food system.

Population growth, urbanization, and economic prosperity have fueled demands for increasing quantities and varieties of food, they said. Intensive agriculture has “too often” responded to this demand with crops bred for “maximum productivity under the protection of broad-scale pesticide applications”, inadvertently breeding out the plants’ own defences, the paper argued.

Overuse of existing antifungal chemicals is exasperating the issue by increasingly rendering treatments ineffective. “Alongside drug discovery and new technology to tackle fungal pathogens, we urgently need better stewardship of existing antifungals to ensure they are used correctly and that they remain effective,” Professor Fisher insisted.

Simultaneously, the paper’s authors noted the emergence of new races of plant-infecting fungi able to overcome both host defences and chemical treatments, as well as the evolution of these traits in existing major pathogens.

Resistant strains of fungi are also able to spread quickly thanks to global trade networks and the increased movement of people, animals and food around the world.

Professor Fisher explained: “The emergence of resistance is leading to a deterioration in our ability to defend our crops against fungal pathogens, the annual losses for food production has serious implications for food security on a global scale.”

Implications for animal and human health

As well as undermining global food security, the researchers note that fungal resistance also represents a threat to animal and human health.

Fungal pathogens are responsible for a broad range of infections in humans and animals and plants, including yeast infections, which can lead to blood poisoning in humans and livestock, and chytrid – the fungus responsible for the ‘amphibian plague’ wiping out species around the world.

Fungicides used in agriculture are leading to the emergence of antifungal resistance in human fungal pathogens, Professor Fisher said. The widespread use of one group of antifungal treatments in particular, a class of antifungals called azoles were cited as a key driver in the emergence of resistant strains of fungi.

Azoles are believed to account for a quarter of fungicides used in agriculture, but they are also used as first line antifungals in the treatment of humans. Their widespread use is thought to be increasing antifungal resistance, by selectively killing off non-resistant strains, with those more resistant to the fungicides remaining. The danger for human health is when this resistance occurs in species such as Aspergillus fumigatus – moulds which thrive on decaying vegetation but are also able to infect those with compromised immune systems, such as cancer patients or those who have received organ transplants, the researchers concluded.

According to the researchers, the more selective use of existing antifungals, the development of new drugs and treatments aimed at silencing the genes of fungi and stopping them from spreading could help to tip the balance in the fight against fungal pathogens.

Source: Science

Published online ahead of print: DOI: 10.1126/science.aap7999

‘Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security’

Authors: Matthew C. Fisher, Nichola J. Hawkins, Dominique Sanglard, Sarah J. Gurr