The demand for plant-based protein is exploding. But as manufacturers try to recreate the taste, texture and appearance of meat and dairy products using plant proteins, they inevitably need to use additives such as flavours, colours and emulsifiers.

Do consumers accept these as being the natural, healthy and clean label products they are looking for or could there be a backlash beckoning?

The numbers don’t point to a backlash on the horizon, according to Liz Specht, senior scientist at The Good Food Institute, a non-profit organisation that advocates a switch to more sustainable foods, such as plant-based proteins or cultured (lab-grown) meat.

Speaking as part of FoodNavigator’s online event Clean Label 2.0 held last week, Specht said most of the growth, particularly seen by non-dairy milk alternatives, is being driven by products that contain additives.

“It’s fascinating to note that the vast majority of this growth is from products that actually aren’t as clean label as some of their predecessors. You can find soy milk that’s just soybeans and water from Westsoy, but you have to go to the tetra-packed shelf-stable natural foods section of the store to find it.

"The vast majority of these milks [...] have carrageenan, gums, lecithin and potassium citrate, etc. Consumers are still flocking to them."

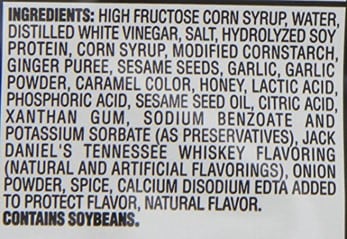

According to Specht, even discerning consumers are open to processing and unfamiliar ingredients when manufacturers explain the benefit to them, and she gave the example of the ingredient list for a Jack Daniels’s meat marinade that says “calcium disodium added to protect flavour” and “potassium sorbate as preservatives”.

Those who predict a backlash against processed plant proteins may also be operating under assumptions of false equivalency, she said, comparing the ingredients list of, say, Beyond Meat’s flavoured and ready-to-eat ‘chicken’ strips to an unprocessed chicken fillet.

It would be more accurate and appropriate to compare processed plant products to processed meat products.

'The opportunities are there'

If consumers do want clean and clear labels, however, the opportunities to replace functional ingredients such as texturisers exist at all production stages of plant-based meat, she said, from ingredient sourcing to fractionation and isolation; raw material processing and product formulation to manufacturing.

“The greater the functionality and sensory performance you can achieve without adding ingredients, the cleaner your label can be.”

Nevertheless, “there are challenges to overcome and a lot of room for innovation” at each stage, she added.

“Scientists are beginning research to uncover which plants are best for plant-based meat production. This can be done by exploring different crops, mapping their genes to better understand how they provide key attributes and using breeding or gene editing techniques to optimize plants for the creation of plant-based meat.”

Meat analogs used to be limited to soy-based tempeh or tofu but other emerging ingredients, such as the fibre-packed jackfruit, are promising, Specht said.

Using biology, chemistry and mechanics

Formulators and product developers can then use a variety of biological, chemical, and mechanical means to get the base ingredients to taste like meat.

The Good Food Institute helps run a course at the University of Berkeley which is investigating ways to encapsulate fat in plant proteins to give a meatier mouth-feel.

Other developments in this area are already on the market. Impossible Food’s, for instance, isolated the molecule soy leghemoglobin and added it to the Impossible Burger to give the metallic taste and red appearance of blood in meat.

Ingredient suppliers are developing natural additives to replace synthetic ones. Mycotechnology grows the fermented filament-like roots or ‘mycelium’ of mushrooms that is then spray-dried and used as a natural bitter-blocking, flavour modifier.

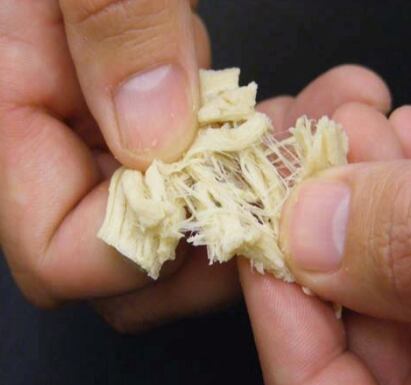

On the manufacturing side, extrusion techniques are commonly used by manufactures to re-shape plant proteins into the elongated structure similar to the proteins found in muscle.

The high temperatures and pressure required by extrusion means it is a relatively harsh and energy-intensive technique.

Dutch scientists recently developed shear or Couette Cell technology that replicates the fibrous texture of steak and could replace extrusion as the go-to method.

Is protein too narrow a focus?

It is important for manufacturers to bear in mind, however, that protein may be too narrow a focus. Most Americans eat around twice the amount of protein that is recommended by national dietary guidelines –(the same is true for Europeans) – yet the majority of people don’t get enough fibre.

Fortifying foods with fibre rather than protein may be more important for making processed foods healthier.

In any case, consumer demand for plant protein may not be as strong as demand for products that are simply meat- or dairy-free, Specht suggested. Sales of plant milks such as almond and coconut, for instance, have overtaken soy despite having a much lower protein content.