The land-use sector, which includes agriculture and forestry, contributes approximately 25% of the human-caused greenhouse gas emissions that are contributing to climate change.

If global warming is to be kept below 1.5°C, the target set by the Paris Agreement, the food sector – alongside other industries – will have to contribute towards efforts to achieve net negative emissions by the end of the century.

However, according to new research published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, climate change policies targeting the food sector could result in increased food prices while also damaging food security.

Threat to prices and availability

“The land-use sector is key for successful climate change mitigation,” explained IIASA researcher and study lead Stefan Frank. “But providing an increasing amount of biomass for energy production to substitute fossil fuels while at the same time reducing emissions from the land use sector, for example through a carbon tax, could also have the effect of raising food prices and reducing food availability.”

Using a scenario that limits global warming to 1.5 °C, results indicate global food calorie losses ranging from 110–285 kcal per capita per day in 2050 depending on the applied demand elasticities. This could translate into a rise in undernourishment of 80–300 million people in 2050, the researchers suggested.

In the study, Frank and colleagues examined the potential impacts of both global action, represented by a carbon tax, and regional and national policies. Though globally coordinated mitigation policies outperform regional or national policies both with respect to emission abatement and food security, “adverse impacts on food security remain”.

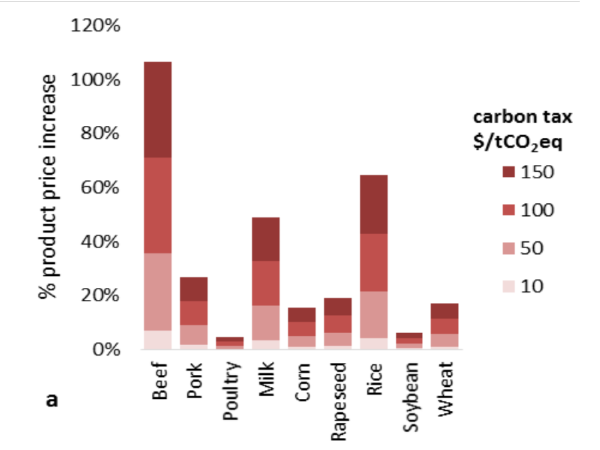

The introduction of a carbon tax, calculated on the basis of how much carbon is emitted in production, would affect different sectors to varying degrees. Carbon intense areas - such as beef, pork, rice and dairy – would be likely to see more of a spike in prices if such taxes were implemented.

No ‘one-size fits all’ answer

In the paper, Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Agriculture Without Compromising Food Security, the researchers use an integrated partial equilibrium modelling framework to examine ways of “relaxing the competition” between climate change mitigation in agriculture and food availability.

They concluded that efforts to reduce deforestation and increase soil carbon sequestration in agriculture could “significantly reduce” greenhouse gas emissions while also avoiding risks to food security.

However, the researchers stress, there is no “one size fits all” solution.

In countries with a large landmass and a high proportion of emissions from land-use change, such as Brazil or Congo Basin countries, there is a “large potential” for forest restoration and preventing deforestation, the study suggested.

Meanwhile, in more densely populated countries with emission intensive agriculture, such as China and India, “strict efforts to reduce agricultural emissions” could lead to “substantial impacts” on food security, without providing “big climate benefits” due to emission leakage.

“In some countries, stopping deforestation could provide a big reduction in emissions with only a marginal effect on food availability,” said Frank. “But a one-size-fits-all approach will not work. In places like China and India, the focus should be on soil organic carbon sequestration and other win-win options that decrease the emission intensity of agriculture.”

Certain farming practices – such as crop rotation, cover cropping, and residue management - can sequester greater amounts of carbon stored in soils, while also offering the potential to increase crop yields.

“You keep the soil healthy, you offset greenhouse gas emissions, and you preserve crop yields at the same time,” explained Frank.

Depending on the climate policy design, the researchers found that soil carbon sequestration on agricultural land could either deliver the same levels of greenhouse gas abatement in the land use sector at considerably lower calorie costs compared to a policy that does not consider the potential of soil carbon sequestration, or even higher greenhouse gas abatement and less pronounced benefits for food security.

The study estimated that increased soil carbon sequestration could offset up to 3.5 GtCO2 (7% of the total 2010 emissions) in 2050, and could reduce the food security impacts of a carbon tax by as much as 65% compared to a scenario without soil carbon sequestration incentives.

Source: Environmental Research Letters

Vol 12, no. 10, doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8c83

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture without compromising food security?

Stefan Frank1, Petr Havlík1, Jean-François Soussana, et al