Mighty Earth’s investigation

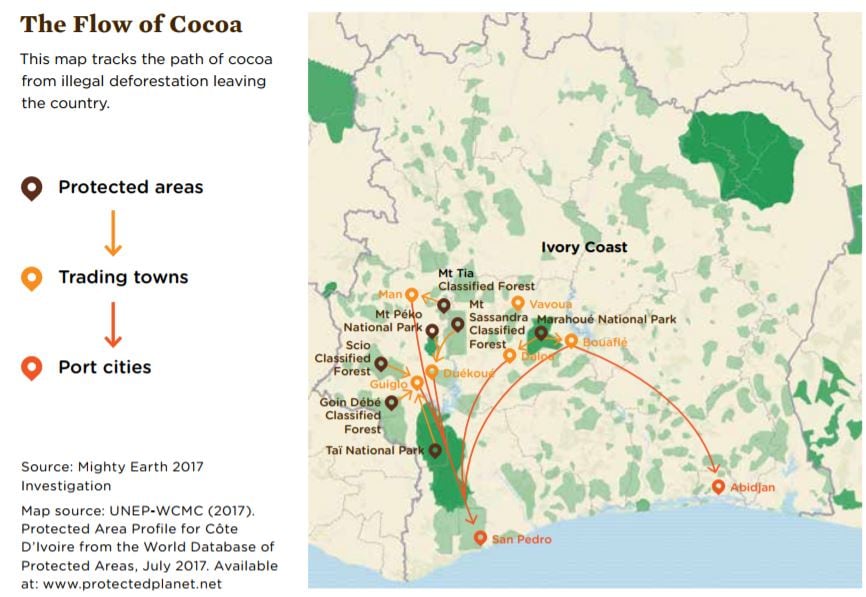

Mighty Earth’s team visited three protected areas: Goin Débé Forest, Scio Forest and Mt. Péko National Park. The NGO also worked with a team that visited Mt. Sassandra Forest, Tia Forest and Marahoué National Park. They traced illegally grown cocoa back to large cocoa processors and big chocolate firms.

The World Cocoa Foundation’s (WCF) president, Mighty Earth’s campaign director and the managing director of NGO the Voice Network have responded to a recent Mighty Earth report that found cocoa-led deforestation is rife.

The report claimed cocoa production has been responsible for a quarter of 291,254 acres of protected forests cleared in Côte d’Ivoire between 2001 and 2014 and 7,000 square kilometers of forest lost in Ghana over the same time, equivalent to 10% of its entire tree cover.

Three national news organizations – The Guardian in the UK, Der Spiegel in Germany and RFI in France - this month broke news from the report that these practices were endangering chimpanzee and elephant populations.

The scale and cause of deforestation

Mighty Earth’s ‘Chocolate’s Dark Secret’ report blamed a “laissez-faire” approach to sourcing by the chocolate industry.

Etelle Higonnet, Mighty Earth’s legal and campaign director, said: "Likely 40% of Ivorian cocoa is coming from these illegal cocoa plantations inside protected areas. That's huge."

Côte d'Ivoire is the world's largest producer of cocoa. Forty per cent of its annual production is equivalent to roughly 700,000 metric tons (MT).

This could mean that at least 17% of the world's yearly cocoa output comes from protected areas, with further volumes from Ghana, Indonesia and Latin America also coming from high conservation areas.

Speaking to ConfectioneryNews, Rick Scobey, president of industry body The World Cocoa Foundation (WCF), whose members include Mars and Nestlé, said: "The real driver for deforestation in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire has been poor small family farmers who have tried to increase their income to generate the school fees they need for their children, and to have enough income for food [by expanding their small farms into forested areas].”

Cocoa & Forests Initiative

What is the industry doing to stop malpractice and do NGOs believe it is enough?

Twelve major players in cocoa and chocolate earlier this year united with public sector partners under the banner ‘Cocoa & Forests Initiative’, aiming to eradicate cocoa deforestation.

The World Cocoa Foundation (WCF) member companies in March issued a joint statement of intent to end deforestation and forest degradation via the platform, in partnership with the Prince's International Sustainability Unit (ISU) and The Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH).

Thirty-five companies are now part of the pledge, including retailers such as M&S, Tesco and Sainsbury's.

The companies will announce a common framework for action in November, but Scobey said one of the key aims will be encouraging agricultural intensification and increased productivity in environmentally suitable areas.

“Our goal is to grow more cocoa, but on less land,” he said.

The WCF president, who joined the organization in July 2016 from the World Bank, told us this approach had begun to take hold in company-led sustainability programs as well as via joint platform CocoaAction.

Other origins at risk of deforestation

- Indonesia - 1.7m acres of forest cleared for cocoa between 1988 and 2007, equivalent to 9% of the nation’s total deforestation for crops. Much of this deforestation has destroyed orangutan, rhino, tiger and elephant habitat, said Mighty Earth.

- Congo Basin - A recent study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo found cocoa expansion could lead to the loss of 176 to 395 sq km of forest in the next decade.

- Peru - Amazon rainforest at risk of deforestation driven by a nearly five-fold increase in cocoa production between 1990 and 2013.

Traceability to first purchase

Scobey said the chocolate industry was also working towards full traceability at farm level – meaning from the farmer to the first point of purchase.

"If it's a coop, they'd have to be able to account where their cocoa is coming from with their farm members. If it's a pisteur who's buying directly from individual smallholders, it would be the responsibility of the pisteur. If it's farmers participating in company programs - as is the case in Ghana where you don’t have the cooperative structure - it would be the responsibility of companies,” he said.

Traceability today is largely in line with the percentage of cocoa that is certified from likes of UTZ, as well as volumes from company programs.

"But that only accounts for a portion the trading companies are sourcing,” said Scobey.

A report published this year by the International Trade Center estimates the global certified cocoa area (Fairtrade International, Organic, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ) makes up 23% of the total cultivated surface.

Scobey said traceability to farm level will take “effort and work to develop robust and verifiable traceability systems, so we need to think through carefully what's the right time line."

WCF hopes to announce a timeline in a framework for action document it will release at climate change meeting COP-23 in Bonn this November.

Signatories to the Cocoa & Forests Intiative

Barry Callebaut, Blommer Chocolate, Callivoire, Cargill Cocoa and Chocolate, Cémoi, Chocolats Halba, Clasen Quality Chocolate, Cocoanect, Cococo Chocolatiers, ECOM Group, Ferrero, General Mills. Godiva, Guittard Chocolate, Hershey, J.H. Whittaker & Sons, Lindt, Marks & Spencer Foods, Mars, Meiji, Mondelēz, Nestlé, Olam Cocoa, Ovaltine, pladis, Ritter Sport, Purdys Chocolatier, Sainsbury's, TCHO, tesco, Toms Group, Tree Global, Touton, Uirevi and Unilever.

‘What we’ve had so far just isn’t cutting it’

Mighty Earth’s Higonnet welcomed the WCF initiative, but claimed it had come after NGOs had persistently pushed the industry to act.

“I’m excited, but at the same time I won’t feel relaxed until we see these commitments on paper.

"We've had a lot of commitments and people talking the talk, a hodpodge of diverse, inadequate sustainability initiatives that have been rolled out for the last decade and a half and those have come concurrently with the total destruction of Ivorian forest.

"What we've had so far just isn't cutting it,” she said.

A fair cut

Higonnet argued that a fairer cocoa price for farmers could alleviate some of the problem.

"We have to be paying the farmers better than we are now. There's no way we can go on like this,” said the campaign director.

She claimed a farmer's share of the profits for a chocolate bar had declined from around 16% in the 1980s to 3.5% to 6% today.

"Now Ivorian farmers make $0.50 a day. Dire poverty is defined as $1.25 a day and poverty is defined as $2 a day. We should at least be aiming to get these people past the $2 a day mark, which means companies need to fork over a much fairer share of the profits."

Scientific research

- A recent peer-reviewed study found three-quarters of land in 23 protected areas surveyed in Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s premier cocoa grower, had been transformed for cocoa production and found a positive correlation between cocoa farming and the absence of primate species.

- A 2015 study by Tondoh et al. suggests misuse of agro-chemicals and growing cocoa in full sun without shade is depleting the fertility of soil in Côte D’Ivoire, making it less conducive to cocoa growing. This can lead farmers to search for fresh land to cultivate their crop, which may come at the expense of protected forests.

- A 2016 study by Barima et al. said the Haut Sassandra classified forest in Center-West Côte d’Ivoire covered an area of 102,400 ha when it was created in 1974. Forests covered 93% of the area between 1997 and 2002, before conflict in the country, and less than 28% in 2015, it said. Researchers suggest cocoa growing has been the main cause.

Higonnet suggested the best approach for companies is to ensure minimum floor prices and to operate a system of flexible premiums, whereby buyers pay a variable added cost on top of fixed farm fate prices to guarantee a living income for farmers and their dependents.

The flexible premium system was recently recommended by a group of NGOs including the Voice Network, Solidaridad and Oxfam, after cocoa prices tumbled to a 10-year low in the New York market in the first quarter.

Antonie Fountain, managing director of the Voice Network and one of the authors of the paper recommending flexible premiums, said: "The problem of deforestation cannot be solved without tackling the underlying crisis of farmer poverty.

“Companies and governments alike should commit to making a living income for farmers the key long term objective.”

'It will not do to point the finger at others'

He added current levels of deforestation may have directly influenced the collapsing cocoa prices, pushing farmers deeper into poverty.

“The long-term deforestation in West Africa also seems to be directly influencing weather patterns and droughts in West Africa, thereby leading to increased income insecurity in the coming years for agricultural communities,” said Fountain.

He said any increases in productivity on environmentally fit land should not overlook diversifying farmer incomes with other crops or activities This can help avoid an oversupply of cocoa and provide a security for farmers, he said.

Fountain agrees with the WCF that stopping deforestation is a joint responsibility.

“It will not do to point the finger at others. Governments have been very loath to enforce protection of classified forests. Companies have been all too willing to turn a blind eye to the deforestation in their cocoa purchasing. Both need to seriously improve their efforts and investments,” he said.

Agroforestry systems

But Higonnet claimed the chocolate industry should also make amends for allegedly contributing to historic deforestation in West Africa.

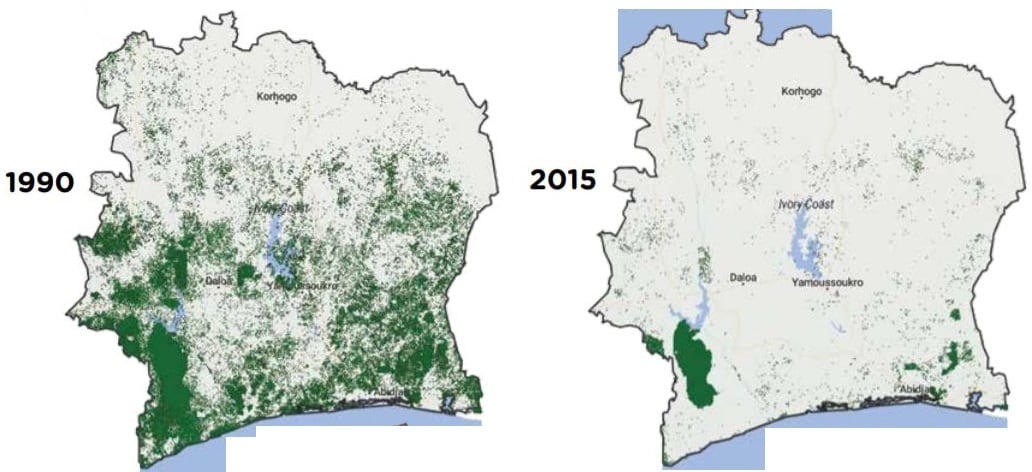

"Côte d'Ivoire lost 85% of its forests between 1990 and 2015 - what are you going to do about that past harm?

"They [the industry] should shift to 100% agroforestry and 40% shade [grown cacao trees]," she said.

The campaign director, formerly of Greenpeace and Amnesty International, said this approach would ensure maximum biodiversity without harming cocoa productivity. "You'll never get back elephants that way, but you'll certainly get back birds, bees and bats...it's not too much to ask for the industry to pay for that."

WCF’s Scobey urged origin governments to complete land-use mapping to gauge encroachment from cocoa.

“Because in many forest areas you could have complementary cocoa production with shade trees in an agroforestry system that generates both the environmental benefits of improved tree cover as well economic opportunities for farmers.”

Mighty Earth has begun developing guidelines for cocoa farms located in areas where the original natural vegetative cover is forest.

A common definition

The NGO is urging companies and governments to work towards a common definition of protected areas.

"The best definition is HCVA (High Conservation Value Areas),” said Higonnet. “Many of these companies have already agreed to HCVA for palm oil,” she said, so the model could be adapted for cocoa.

The campaign director encouraged the chocolate industry to look to the success of the Brazil Soy Moratorium for a model, which she said had curbed deforestation in the Amazon while increasing profits and productivity for farmers.

Avoiding forced evictions

Mighty Earth’s report alleges chocolate companies are taking advantage of the Ivorian government’s lack of enforcement to protect forested areas.

But how do you deal with the farmers already operating in protected areas?

Scobey claimed: “The Mighty Earth report doesn’t acknowledge the social dimension.

“We need to make sure the enforcement of restrictions on farmers who depend on cocoa for their livelihoods is implemented in a way that doesn’t hurt the communities…we need to find alternative livelihoods for those people,” he said.

The Voice Network’s Fountain added: “Violent forced evictions, such as we have recently seen from classified forests in Côte d'Ivoire, are not the way forward.”

Higher benchmarks to be a cooperative?

Mighty Earth’s report claimed cocoa grown in protected areas is often cultivated by settlers that clear or burn existing trees. They sell their beans to middlemen called “pisteurs”, who transport volumes to villages and towns and sell to cooperatives. These coops then sell either directly or through another middleman to the industrial cocoa grinders at ports in Côte d’Ivoire, who supply the world’s largest chocolate firms.

Mighty Earth argues governments should set higher benchmarks for groups to become a cooperative.

“These people call themselves cooperatives and appear to have papers....They are really just stores run by a guy who's profiting immensely,” said Higonnet.

"[The standards] we have now are far too low...It just cheapens the work done by genuine coops...the authorities need to step in and do a much better job,” she said.

Technology: 'The way of the future'

For the chocolate industry, Mighty Earth is pushing companies to commit to zero future deforestation.

"It's really not that hard to say no new deforestation,” said Higonnet. “We now have amazing technological advances,” she said, such as satellite mapping from NGOs, which is often free to use.

WCF’s Scobey said technology to support traceability and farm mapping was fast evolving and becoming cheaper.

For example, Barry Callebaut is using a mobile app named ‘Katchilé’ used by appointed village coordinators and field agents at farm-level to collect data on deforestation and reforestation.

Mondelēz's has also mapped 115,000 hectares farms that are part of its Cocoa Life program and has made the data public, while Ferrero is working from Mighty Earth and says it is on course to trace its entire cocoa supply to farm gate by next year. Half can be traced back to date.

Scobey added third party observers can also more readily monitor company deforestation-free commitments using satellite data imagery from civil society organizations like World Resources Institute or Global Forest Watch.