Animals who eat at sea inherit a chemical record reflecting where they fed, said the study from the University of Southampton.

The research team, led by Dr Clive Trueman and PhD student Katie St John Glew, built maps of chemical variation in jellyfish caught across the North Sea and assessed accuracy and precision through dietary-isotope-based location methods.

Predictable spatial variations in carbon and nitrogen isotopes in primary production provide a basis for stable isotope-based location.

Chemical test

They compared chemical signals in scallops and herring caught in known places across the North Sea, and used statistical tests to find areas of the North Sea with the most similar chemical compositions.

The chemical tests were able to link scallops and herring to their true locations and can be used to see if the chemical composition of an animal matches a claimed area of origin.

“Accuracy and precision for retrospective isotope-based location in the North Sea were of a similar order to light-based location devices, with 75% of individual scallops assigned correctly to areas representing c. 30% of the North Sea, with a mean linear error on the order of 102 km,” according to the study.

Dr Trueman, associate professor in Marine Ecology, said there is no way as yet of testing where a fished product was caught.

“Understanding the origin of fish or fish products is increasingly important as we try to manage our marine resources more effectively. Fish from sustainable fisheries can fetch a premium price, but concerned consumers need to be confident that fish really were caught from sustainable sources.”

A broad look at food fraud

Meanwhile, researchers from the University of Copenhagen have said “non-targeted” methods of analysis can reveal more food fraud than is currently being detected.

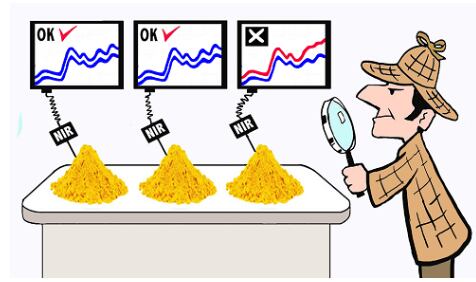

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR) gives a physicochemical “fingerprint” of raw materials and ingredients used in production and this information can be used to detect whether a foodstuff or ingredient has been modified, said the team from the department of food science (FOOD).

They reviewed the use of NIR spectroscopy to detect food fraud in the scientific journal Current Opinion in Food Science.

Professor Søren Balling Engelsen, co-author of the article, said analyses used today are only spot checks and are typically targeted towards a single kind of food fraud.

“We would like to move away with this old-school methodology and instead take a “non-targeted” physicochemical fingerprint of the foodstuffs. By using fingerprints and contrasts we can determine whether a given batch of raw materials or ingredients are defective or different compared to the usual,” said the head of Chemometrics and Analytical Technology at FOOD.

With spectroscopic monitoring it is possible to examine ingredients and raw materials that go into production, to reduce production errors or those of a lower quality than the recipe dictates.

An ingredient that can be manipulated by suppliers is gum arabic (E414), which has properties as a stabiliser, chewing properties and flavour release and can be found in Ga-Jol.

“However, it is easy to adulterate food with gum arabic, when it appears in the form of freeze-dried powder, which many suppliers have gradually started to sell,” said Søren Balling Engelsen.

“Previously, it was found most often in the form of “tears” from the acacia tree – that is, as large amber-like clumps that cannot be easily forged. But it has been difficult to obtain high quality gum arabic because of the war and unrest in the growing areas (South Sudan).

“As a powder, it is easy to falsify the gum arabic by mixing an inferior quality with the good and sell it all as being of a high quality.”

Balling Engelsen said the methods have been known and developed for 20 years and have become cheaper over time.

“The use of NIR spectroscopy to monitor food quality was already endorsed in the 1970s when Canada began to replace the chemical requiring and cumbersome Kjeldahl analysis with NIR spectroscopy to analyse their cereals for the protein content.

“An increased use of NIR spectroscopy will definitely be able to save us from many forms of food modification that could be of more or less serious kinds – from receiving lower quality products to becoming seriously ill.”