There are two reasons why fish and seafood producers and manufacturers should feel optimistic about exploring the Turkish market, according to the Norwegian food and fishery research centre Nofima.

The first is due to the country’s dwindling fish stocks in the seas around Turkey – the Mediterranean and Black Sea - which have suffered from long-term over fishing. This, coupled with a relatively modest and under-developed domestic aquaculture industry means demands for imports are increasing.

The second is down to a growing demand for fish as Turkish consumers become more health conscious.

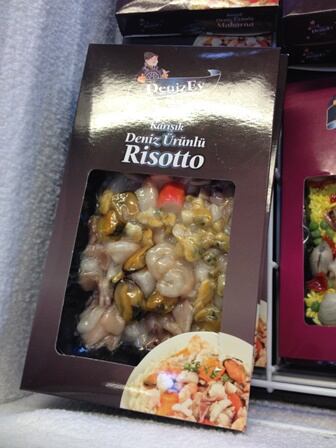

Shopping habits in the country are also changing, especially in big cities, and while many people are still attached to buying fresh, whole fish from traditional fishmongers, supermarkets are growing in importance and are increasingly stocking shelves with processed fish products.

Nofima scientist Gøril Voldnes, who specialises in cross-cultural business relationships, told FoodNavigator: “There is definitely a market for processed food in Turkey. In all super-hyper markets we saw a large variety of processed, ready-to eat or easy to prepare fish dishes. We didn’t observe that much marinated fish – but both breaded fish and paella dishes were in lots of different styles.”

Fishing for success

Salmon – In 2015 Turkey imported around 8,000 tonnes of salmon from Norway, twice as much as in 2010, and growing.

Mackerel – A staple for Istanbul’s much-loved street food snack balik ekmek – fresh grilled mackerel served in crusty bread with spices, lemon, tomatoes and cucumber – and popular nationwide, Norwegian mackerel has enjoyed a “strong position” in Turkey for the past 20 years, says Nofima.

Herring has been growing in popularity in recent years due to tourism from Russia and other Eastern European countries.

Pollock is also popular because it is cheap and similar in taste to local species. Main imports come from Iceland.

Cod has so far had little success in the consumer market but has the potential to be successful in the restaurant market. Turkey receives around 35 million foreign visitors each year which has led to a thriving internationally-influenced culinary scene in major cities, where cod features on menus. Once it becomes commonplace in restaurant menus, it is likely to gain traction in consumer markets, says Nofima. Turkish people also eat out at restaurants on a regular basis – around two to three times a week – and so this could be a good entry point for manufacturers and seafood processors wishing to launch a new product.

Mintel data shows that demand for processed fish grew by 5% in 2014, although it predicts this will dip slightly in coming years.

Sustainability, on the other hand, does not seem to figure high on Turkish consumers’ priorities when choosing seafood.

According to certification board the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), there is very little demand for MSC-certified seafood in Turkey – just one metric tonne in 2015 out of a global total of 659,399 tonnes for the 2015/2016 period.

However, this is expected to rise for 2016 as Ikea adds to its range of MSC-certified produce, it said.

Challenges

Despite this clear opportunity, entering the market is not without its challenges.

Turkish people currently eat a relatively small amount of fish compared to other countries – six kilos of seafood per person annually compared to the average Norwegian who eats around 40 kg per year. The relative rarity of fish and seafood, especially in inland areas, has led to common misconceptions.

“The lack of knowledge of fish has even created the myth that fatty fish, combined with dairy products, can be so dangerous that one can die from it," says Voldnes. "Thus, to increase consumption information and promotional campaigns are needed that encourage consumers to adopt new eating habits.”

Manufactures, importers and processors need to work together to create information campaigns to dispel such myths, and given the popularity of television in Turkey, this would be an ideal media channel, she said.

There are also some regulatory barriers to trade.

Last year the government required importers to provide special documentation proving all fish entering the Turkish market was dioxin-free. This meant shouldering the costs of doing tests on batches of fish or sending samples to an independent bureau in Germany, both of which could be costly and time-consuming.