“A diet with [current] levels of meat consumption, but entirely devoid of ruminant products - beef, mutton, dairy - carries lower GHG emissions and has higher area efficiency than a vegetarian diet rich in dairy,” said author David Bryngelsson.

The proposed poultry diet, with protein sources derived from chicken and eggs would mean EU targets of reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions could be reached while still allowing for meat to be eaten at current levels.

“You could say that chicken is like an electrical car – it is a better alternative, yet still very similar to what we are accustomed to,” he added.

Cattle - a hefty carbon footprint

Cattle consume huge amounts of feed to produce a relatively small amount of meat whereas poultry have a high feed-to-meat productivity, said the study. Cattle ranches were also responsible for vast swathes of deforestation, accounting for 13% of anthropogenic GHG emissions.

And while methane emissions are exempt from the European Union emission trading system, the Kyoto Protocol identified methane as a major contributor to global warming– and cud-chewing cows are big methane gas producers.

Furthermore, said Bryngelsson, cows have a much slower reproductive cycle compared to poultry, producing on average one calf per year compared to chickens, which have around 150 chicks per year.

A necessary compromise?

The study, published as Bryngelsson’s doctoral thesis, looked at GHG emissions of different model diets. Comparing the average Swedish diet – high in beef and dairy – to vegetarian, vegan and poultry-based ones, he claimed that the greatest benefits came from cutting out cattle products.

In fact, the environmental benefits in switching from cattle to poultry were even greater than a switch from poultry to vegan.

He also predicted that if more consumers ditched beef and dairy en masse, food manufacturers would respond with substitute products.

“Greater demand for alternative products such as vegan cheese will drive a development where they become even tastier. Poultry meat based meatballs already taste like traditional ready-made beef meatballs.”

Animal welfare

Bryngelsson said that his study also took into account the possibility of improvements in animal welfare and breeding conditions, claiming the space given to chickens could be increased five-fold without noticeably affecting the impact on the environment.

But Dil Peeling from NGO Compassion in World Farming said that this was unlikely to happen.

“At least 70% of chickens are raised in intensive factory farms in the UK, while in the EU over 90% are raised in intensive factory farms. Conditions are less humane than those for cattle - encouraging people to eat more chicken simply isn’t the way to go."

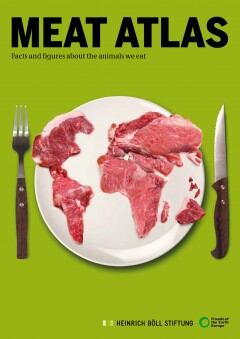

A 2014 Friends of the Earth report warned that global demand for meat - and cheap chicken in particular - was already skyrocketing in developing countries.

“Booming economies in Asia and elsewhere will see around an 80 per cent increase in demand for meat and dairy products by 2022. If [current meat consumption trends continue] the world’s farmers and agricultural firms will have to boost their meat output from 300 million tonnes to 470 million tonnes by 2050.”

Source: Chalmer’s University of Technology publications

To read the full thesis click here

PhD thesis title: "Land-use competition and agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in a climate change mitigation perspective"

Author: David Bryngelsson