According to the Committee on World Food Security (2012) food security is defined as when "all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life."

“The four pillars of food security are availability, access, utilization and stability. The nutritional dimension is integral to the concept of food security,” the definition states.

Yet what does this really mean when hundreds of millions of people are hungry and undernourished, and the already serious challenge of providing food security is expected to become more difficult as populations grow?

Feeding the more than 9 billion people expected to be living by 2050 is a serious challenge. Indeed, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) deputy director-general has suggested that agricultural production needs to increase by 70% worldwide, and by almost 100% in developing countries, in order to meet growing food demand.

But is the answer as simple as that?

There is no silver bullet

Food security, in particular the food supply and demand challenge, is complex.

Even just filling the gap we have currently would require huge investment and time – during which population growth would increase pressure on food availability and see the same problem reoccur, say researchers. Indeed, if investment in growing agricultural capacity could be increased just to backfill the current shortfall, expect to see considerable lags – in the 25-year plus range – between when investments are made and when productivity increases are fully apparent.

“The food security pathways that are most often cited, particularly within the agricultural science world, such as crop breeding and crop management are important, but are only part of the solution, and do not constitute silver bullets for solving the food security challenge,” said researchers led by Brian Keating from the CSIRO Sustainable Agriculture Flagship, writing in Global Food Security.

Not a single issue or measure

To guide policymaking and action in this area, the main drivers affecting future food supply and demand need to be understood, while research needs to provide insight into what determines food security and how different aspects can be measured.

Many studies and analyses have used one of four different food security indicators: food prices, calorie availability, child malnutrition and the prevalence of undernourishment.

Yet these aggregate outcomes do not reveal much about the true drivers of food security issues.

“When aggregating the needed increases in global production, it matters a lot what units are used and how different commodities are included – whether as mass, calorific content or monetary value,” said researchers writing in Food Policy.

Indeed, they noted a previous FAO report that estimated a 60% increase in food requirements using monetary value as the weighting fact, but anticipated shifts in consumption patterns towards higher value commodities globally mean that a 60% increase in monetary value does not imply a 60% increase in production volume for each crop or livestock type.

Such outcomes are by no means uniform, warn experts, who say that projections for prices and calorie availability in particular vary widely, while the results for child malnutrition and undernourishment seem to be fairly consistent.

In addition, to date there are no global analyses of food security in which different levels are addressed consistently to explore the continental, regional, national and local contexts and solutions.

“This is a challenge that needs urgently to be addressed so that we can understand how things play out on the ground given the need to tailor approaches to local needs and/or conditions,” said researchers writing in a separate Global Food Security study.

Pathways to security

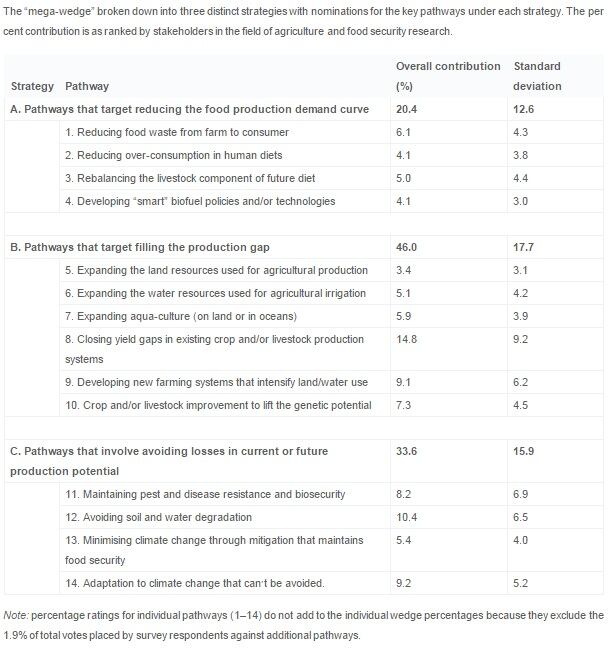

According to Keating and colleagues, the growing food demand challenge could be seen to consist of three component food ‘wedges’ classed according to their target pathways: pathways that target reducing food demand; pathways that target increasing food production; and pathways that target sustaining the productive capacity of food systems.

The team suggested that breaking down the issues and potential solutions to food security into more digestible components and ‘pathways’ could aid in planning, policy and investment responses to food security.

“Within these wedge classes, we nominate 14 pathways that are likely to make up the food security ‘solution space’,” say the team. “These prospective pathways are tested through a survey of 86 food security researchers who provided their views on the likely significance of each pathway to satisfy projected global food demand to 2050.”

Keating’s findings suggest that targeting pathways that contribute to filling the production gap was ranked as the most important strategy by surveyed experts, who suggested that 46% of the required additional food demand is likely to be achieved through pathways that increase food production.

“Pathways that contribute to sustaining the productive capacity are nominated to account for 34% of the challenge and 20% might be met by better food demand management,” said the team.

“However, not one of the 14 pathways was overwhelmingly ranked higher than other pathways.”